Research

September 2, 2020

State Policies for Addressing Surprise Medical Bills: Recent Trends Provide a Roadmap for Federal Policymakers

Executive Summary

- Surprise medical bills (SMBs) have been a major focus of federal policymakers for the better part of two years, but there remain divisions on how to mediate payment disputes between providers and payers.

- In the absence of federal action, 30 states have regulated SMBs, but states cannot apply their regulations to self-insured, employer plans, which are regulated by the federal government under the Employee Retirement Income Security Act of 1974.

- Existing state laws provide a valuable introductory perspective about recent trends and prevailing approaches, and while they vary in nuanced ways, there is a remarkable amount of consensus in their approaches and they provide a roadmap for a federal solution.

- State solutions consistently prohibit balance billing of patients in cases of SMBs, removing patients from the middle of provider and payor disputes, and increasingly rely on independent dispute resolution processes to determine appropriate payments where providers and payers cannot agree.

Introduction

The issue of surprise medical bills (SMBs) had been a major focus of federal policymakers since 2019 until the coronavirus pandemic. Yet even with COVID-19 dominating both the headlines and policymakers’ attention, SMBs have remained part of the conversation—not simply because COVID-19 is bringing large health care bills to some patients, but also because any legislative response package is a potential vehicle for reform. Indeed, there has been speculation that any next bill could contain SMB reforms. It is critical that policymakers understand the potential benefits and drawbacks of reform options.

Though attention from federal lawmakers is relatively recent, the challenges to patients, providers, and insurers posed by SMBs are hardly new. In fact, 30 states have enacted some level of SMB protections for patients, and a number of states including Michigan, Ohio, and Pennsylvania are currently debating new legislation. As federal and state policymakers continue to work toward a legislative agreement addressing SMBs, a review of the approaches taken by many states in recent years elicits two key conclusions that provide a helpful roadmap for a federal solution.

First, there is broad consensus among the various state approaches. States have widely agreed that patients should be protected from SMBs, and three-fifths of states have undertaken measures to do so. Additionally, over two-thirds of states that regulate SMBs mediate payment disputes between payers and providers for out-of-network (OON) services. Finally, more than half of the states regulating SMBs have included an independent dispute resolution process (IDRP) as part of their approach, including most states that enacted SMB laws within the last year.

Second, there simply has not been enough time to determine the full impact of these laws. Going forward, transparency around state regulations will be crucial to determining the impact of these policies on patients, providers, payers, and health care costs. Any federal legislation should prioritize ensuring data on outcomes are publicly available.

Despite the work states are doing to protect patients, a simple fact remains that because of existing federal law, only a portion of patients will be protected by these laws if the federal government does not act. The American Action Forum will consider policy responses currently being debated in Congress in a forthcoming paper later this year.

Background

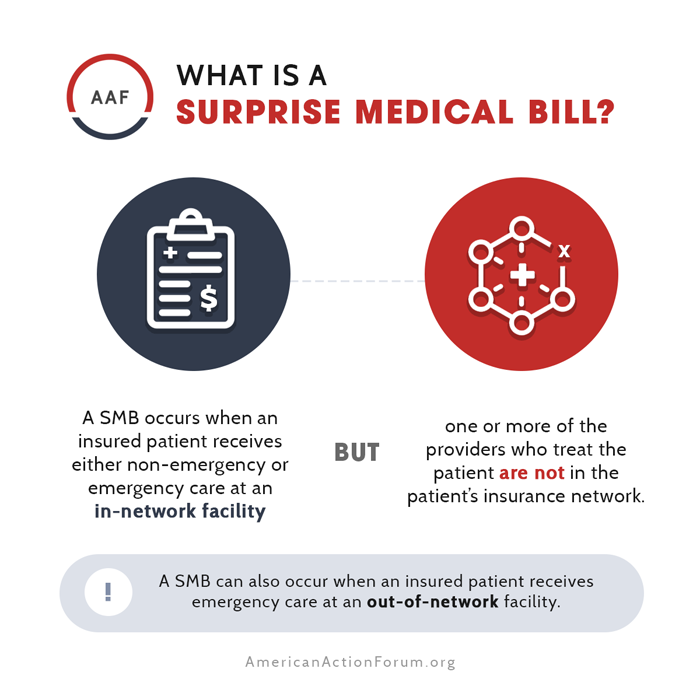

What is a Surprise Medical Bill?

Patients may legitimately be surprised at their deductible and cost-sharing requirements for covered services received from an in-network provider, but these charges do not constitute a SMB. A SMB instead occurs when an insured patient receives either non-emergency or emergency care at an in-network facility, but one or more of the providers who treat the patient are not in the patient’s insurance network. Alternatively, a SMB can occur when an insured patient receives emergency care at an OON facility. In these instances, providers can and often do bill the patient for the difference between their charged rate and what the insurer agrees to pay. This is what is known as “balance billing.” While in-network providers agree to accept a negotiated rate from the insurer for their services, OON providers are not similarly limited.

The Greatest of Three

The Affordable Care Act (ACA) included a provision to partially address SMBs that required insurers to treat OON emergency care as if it were in-network for the purpose of patient deductibles, cost-sharing, and maximum annual out-of-pocket limits. But the ACA did not prohibit balance billing of patients by the OON emergency care providers for the difference between what they charged for the service and what insurers paid. Federal regulations attempted to mitigate this through the “greatest of three” rule. Under this rule insurers are required to reimburse for OON emergency care at either the amount negotiated with in-network providers for emergency services, the usual, customary, and reasonable (UCR) rate for the geographic region, or the amount Medicare would pay for the service, whichever is greater.[1] The purpose behind this rule was to ensure providers received adequate reimbursement in order to reduce the need for, and frequency of, balance billing. Unfortunately, the rule is hard to enforce, as in-network rates are often not publicly available and the UCR is ill-defined.

The Employee Retirement Income Security Act of 1974

While states have stepped into the gap and sought to provide patients with protections from SMBs, states cannot apply those protections to all their residents. The Employee Retirement Income Security Act of 1974 (ERISA) preempts state regulation of the self-insured health plans typically run by large employers, and as a result only the federal government can regulate SMBs in the context of self-insured plans. As a result, notwithstanding any state actions, the problem of SMBs cannot be fully addressed without federal action.

State Approaches to Surprise Medical Bills

As detailed in Appendix 1, in the absence of additional federal protections for patients, 30 states have implemented their own solutions.[2] Many of these have been enacted within the last six years, making it somewhat difficult to draw definitive conclusions about the impact of the more recent approaches. Though there is variation among state approaches and their relative effectiveness, there is also a striking amount of similarity in their content and design. Both the experiences of states as they have implemented SMB solutions, as well as the consensus that is forming around recent state initiatives, can inform the efforts of federal policymakers.

Patient Protections

Thirty states have taken action to respond to SMBs, and all have restrictions in place on balance billing patients for emergency services. Most of these states prohibit balance billing for emergency care entirely. Similarly, 22 of the 30 states limit balance billing by OON providers delivering care at an in-network facility.

State lawmakers and regulators have largely unified around the principle of holding patients harmless for any additional costs beyond their in-network deductibles and cost-sharing requirements when they receive OON services due to circumstances beyond their control, and further that patients should be excluded from payment disputes between payers and providers.

Of note, however, legislation currently under consideration in the Michigan legislature runs counter to this consensus in as much as it would allow insurers to make the payment for OON service to the patient, who would then pay the provider, rather than make the payment directly to the provider.[3] This structure could result in patients being dragged into any dispute resolution if providers feel the payment is unfair. Even among competing federal proposals to address SMBs, there is consensus around this point. Patients should not bear the cost of OON services when seeking emergency care, or when they have made a good-faith effort to use in-network care.

Payment and Dispute Resolution

Prohibiting providers from balance billing patients and requiring insurers to limit enrollees’ financial liability is relatively straightforward. Attempting to reconcile disputes between providers and payers over proper payment amounts for OON care, however, is a more difficult undertaking, and it is on this point that federal policymakers have struggled to find consensus. Any effort to mediate between providers and insurers risks preferencing one party over the other, disrupting existing market forces, and impacting insurance premiums and provider networks. Providers, insurers, patients, and policymakers have competing interests in this matter that make consensus difficult. But even on this thornier issue, state approaches demonstrate more consensus than one might expect and provide a roadmap for a federal solution.

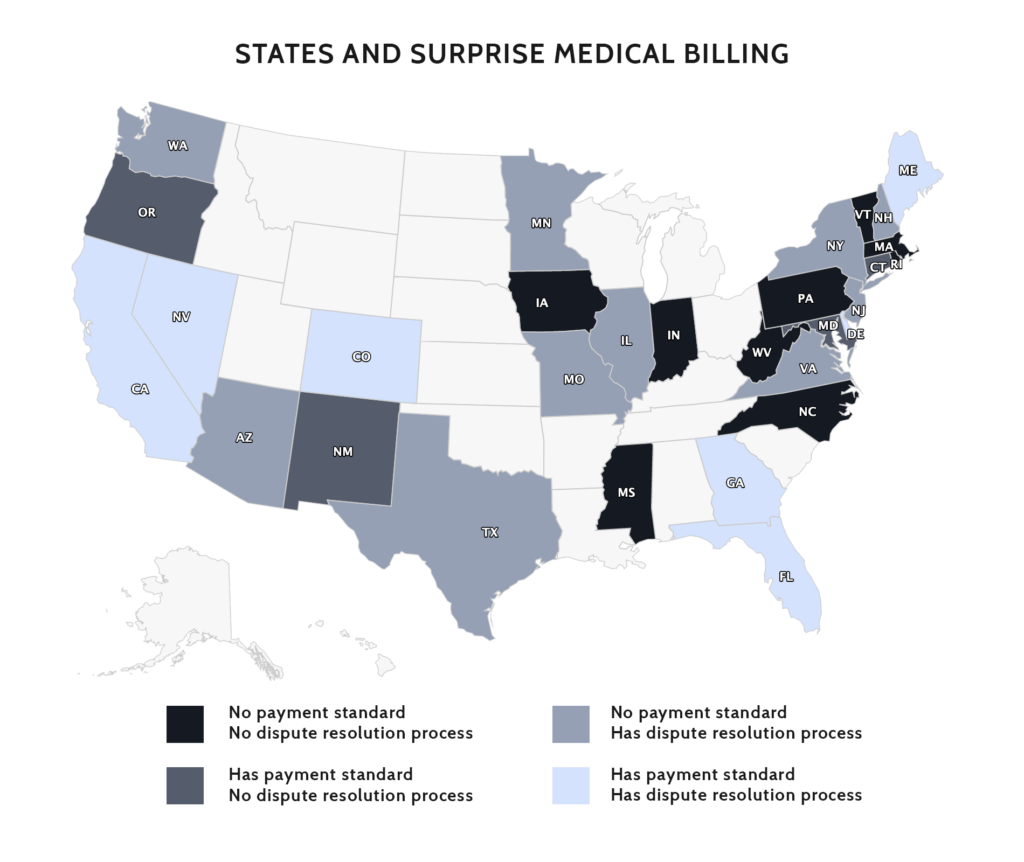

Of the 30 states that have acted to regulate SMBs, only nine have not included a framework for regulating payments in cases of OON care. Four states (see map) have opted to establish guidelines for insurer payments to OON providers, in effect setting payment rates. Alternatively, 10 states (see map) have enacted some form of IDRP to resolve payment disputes between providers and insurers over OON care. Finally, seven states that have established an IDRP—California, Colorado, Delaware, Florida, Georgia, Maine, and Nevada—combine the IDRP with a rate-setting component.

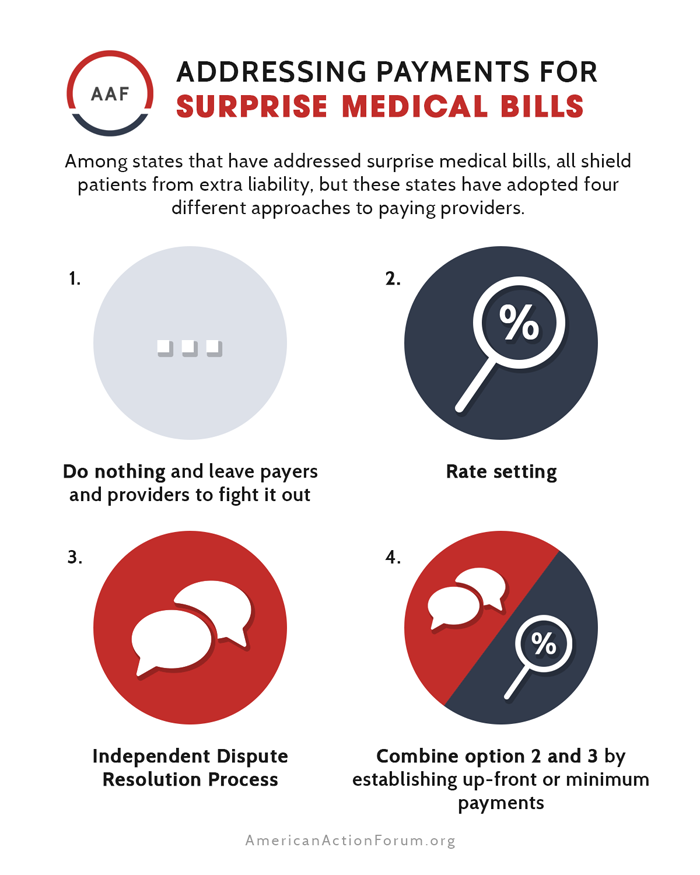

In broad strokes then, there are four categories of response that state have taken to address provider payment for OON services: (1) do nothing and leave payers and providers to fight it out; (2) rate setting; (3) IDRP; and (4) combine options 2 and 3 by establishing up-front minimum payments, while also providing an IDRP that providers can access under specified circumstances. There are pros and cons to each of these approaches as well as important variations within each of these approaches among states that alter the impact of the policy, but states have largely gravitated to options 3 or 4. The following considers each of these responses.

1. States act to protect patients but leave providers and payers to negotiate payment.

Nine states (see map) have taken this approach, providing varying degrees of protections for patients facing surprise medical bills for OON care but leaving it to providers and payers to work out how this care will be reimbursed. This approach has the advantage of protecting patients and neutralizing potential political consequences for elected officials, without requiring policymakers to pick winners and losers between providers and insurers. At the same time, prohibiting balance billing—especially in the case of emergency care where doctors are required by law to provide services—without tackling payment disputes puts providers at a disadvantage when negotiating with insurers, particularly when network standards for emergency care are vague.

2. States set payment guidelines for what providers will be paid for OON care.

Under this second—and least common–approach, states pair patient protections with some manner of rate setting for OON health services. Four states (see map) have undertaken an exclusively rate-setting approach to payment resolution. In Oregon, rates are set based on the allowable charges for commercial carriers in 2015 and then adjusted for a variety of factors including geographic region and case severity, among others. In New Mexico, payments are set at the 60th percentile of the allowable commercial charges for the same service, provider type, and geographic region in 2017, unless the amount is less than 150 percent of the 2017 Medicare rate for the service. Connecticut separates emergency and non-emergency OON payments. For non-emergency OON care at an in-network facility, insurers must pay the in-network rate for the service, but the insurer and provider can mutually agree to an alternative payment. For emergency care the insurer must pay either the in-network rate, the 80th percentile of all charges for the same service, provider type, and geographic region according to a database overseen by the state insurance commissioner, or the Medicare rate, whichever is greater. Finally, Maryland has an all-payer system that in effect sets prices for what insurers pay hospitals.[4] As for direct payments to physicians, Maryland’s guidelines are complex, varying based on the type of insurance (HMO vs PPO) the type of provider, and whether the provider is a direct employee of the hospital system.[5]

Having the government establish the payment rate for OON care is generally seen as the preferred solution of insurers. If OON providers are required to accept a payment that is less than what the insurer would pay to an in-network provider or below what the provider would have negotiated with the insurer, the insurer comes out ahead. Further, such a scenario might be expected to incentivize providers to join networks while at the same time giving insurers more leverage in negotiations—insurers who might also be less inclined to include providers in their network if the rate is tied to the median in-network rate.

How the payment rate is set is a crucial question, as is whether government regulators can correctly determine appropriate levels of compensation. For rate setting to work, the rates must be equitable and providers must be paid enough to cover their costs and allow for a reasonable profit. At the same time, regulators need to be aware that excessive increases in insurer costs will result in larger out-of-pocket costs and higher premiums for enrollees. Similarly, rates need to be set so as not to advantage either party in negotiations around networking. The federal government regulates payments through programs such as Medicare and Medicaid, but those rates are frequently set below providers’ costs and result in cost-shifting to other payers in the health care system. Additionally, government regulators may not be particularly adept at adjusting payment rates to keep up with changing practice patterns, medical breakthroughs, or other factors. Further, most states that have adopted rate setting have utilized an all-payer claims database, but federal policymakers are unlikely to unify around such an approach. There is also a risk anytime governments engage in price setting that prices will be influenced not by data, but rather by political pressure.

3. States establish an IDRP to mediate between providers and payers and determine appropriate payment for specific cases.

The most common approach to payments for OON care among states that have addressed SMBs has been some form of IDRP. Ten states (see map) have established IDRPs without any rate-setting component. Whereas insurers generally prefer a rate-setting approach, providers have broadly endorsed IDRPs. The advantage to the provider is the opportunity to present specific factors in a case that might affect what a reasonable payment would be. In theory, a robust IDRP could also lead to more network participation because after several rounds of arbitration, providers and insurers would have a clear idea of where payments are likely to end up. But to say that providers favor arbitration is only part of the story. How the IDRP is accessed, what metrics are used in determining payment, and the degree to which data about outcomes are available all matter when designing an IDRP.

Both Washington and Virginia have enacted legislation within the last year protecting patients from SMBs. While neither state elected to embark on a rate-setting regime, both laws instruct insurers and providers to agree on a commercially reasonable rate of payment for OON care. In the absence of agreement between insurers and providers, however, both states established IDRPs that providers can appeal to. Washington and Virginia utilize a final-offer arbitration model where both parties submit a proposed payment, and the arbitrator chooses between the two. In both states the arbitrator is instructed to consider any evidence presented by the parties in support of their offer, the specifics of the case including the patient’s condition, and the location where service was provided, and well as data from a state-maintained claims database.

In the case of New York, criteria for choosing between the two payment offers include whether there is a “gross disparity” between the provider’s charged rate and what the provider has received for the same services in similar situations, or what the insurer typically pays for the service in similar situations. Additionally, provider training, education, experience, usual charges, the specifics of the case and the patient, and the UCR are all explicitly listed as factors for the arbitrator to consider. New York defines the UCR as the 80th percentile of all (non-discounted) charges for similar services, performed by similar providers, in the same geographic region. New York maintains a database of charges for the purpose of this calculation. The New York law also includes reporting and transparency requirements for physicians, facilities, and insurers to keep patients informed of their networks and potential costs. Finally, the cost of arbitration is paid by the losing party, unlike many states where the cost is shared regardless of outcome.[6] This is an important detail for providers, particularly for smaller practices, that might find the cost of arbitration a barrier to pursuing it.

New York’s law was enacted in 2014, making it one of the few states where some conclusions can be drawn, although much of the data is limited to surveys or is anecdotal. Overall, New York’s law does appear to have helped patients. State officials report that consumer complaints about SMBs are down dramatically.[7] As of 2018 there had also been an overall decline of 34 percent in OON bills, indicating networks are expanding.[8] Both insurers and providers believe the law has tilted contract negotiations in favor of providers.[9] At the same time, some have expressed concerns that tying arbitration decisions to the 80th percentile of provider charges, which are somewhat arbitrary, could lead to increased spending on health care and ultimately higher insurance premiums. The average IDRP decision has been about 8 percent above the 80th percentile of charges for the service in question.[10] Survey data indicate that providers are more satisfied with the process than insurers overall, but arbitration decisions have been effectively split in favor of providers and insurers.[11]

In Texas, a new IDRP took effect January 2020. Texas has separate IDRPs for medical facilities and providers. Facilities can use a non-binding dispute mediation process; the mediator, however, does not determine final payment, and if the insurer and facility do not come to an agreement, either party can pursue litigation. Providers can initiate arbitration between 20 and 90 days of receiving payment. Texas also has a 30-day informal settlement period prior to beginning the formal IDRP, and the settlement period can be extended by mutual consent. If the IDRP is triggered, the arbitrator has 51 days to choose between the provider’s billed charges or the insurer’s final offer. Criteria the arbitrator must consider include: physician education and experience; the specifics of the case; the 80th percentile of billed charges for similar providers in similar cases in the same geographic area; and the 50th percentile of rates paid by insurers to similar providers in similar cases in the same geographic area. Texas allows bundling of IDRP cases—an important provision for providers. For example, multiple services for the same patient or multiple patients covered by the same insurer who received a similar service can be combined in a single IDRP case if the total amount in dispute is less than $5,000. So far, 38 percent of IDRP requests have been bundled. Both parties split the cost of arbitration regardless of outcome.[12],[13]

Although Texas’s law has only been in effect for eight months, in July the Texas Department of Insurance (TDI) released a report on the first six months. A few data points stand out. There have been only 19 patient complaints about balance billing filed with TDI in the first six months of 2020, compared to 546 in the first six months of 2019. Texas is clearly succeeding at protecting patients from SMBs. Also through the first six months of 2020, TDI has received more than 9,000 requests for an IDRP, and TDI notes that the numbers of requests have increased each month. Through June, the average billed amount for cases that have gone to IDRP has been $1,611, while the original payment amount has been $191, and the average settlement has been $1,016. Perhaps noteworthy, through June, 85 percent of IDRP requests have been initiated by one of three large physician staffing firms. At the same time, it doesn’t necessarily follow that IDRP applications will be limited to large firms. Practice patterns are more likely to drive utilization of IDRP. Even a small practice providing emergency department services with a mean claim of $900 could quickly compile multiple bundled applications for IDRP given the $5,000 cap.[14]

Ultimately, the effectiveness of an IDRP depends on how accessible the process is to providers. For example, Arizona, New Hampshire, and New Jersey all set a dollar threshold beneath which claims cannot be taken to an IDRP. This functionally removes the IDRP as an option for many cases, particularly if the IDRP does not allow multiple claims to be bundled together. Additionally, the criteria used in the IDRP, whether those criteria must be considered or simply may be considered, the cost associated with arbitration, and whether there is detailed public reporting on the outcomes of arbitration are all important to consider.

4. States set guidelines for minimum or upfront payments but also provide an IDRP for providers and insurers to appeal to in specific cases.

Seven States—California, Colorado, Delaware, Florida, Georgia, Maine, and Nevada—have taken the approach of pairing upfront rate setting with a backstop IDRP. This approach has unique benefits and challenges, which differ greatly among states based on specific policy design.

While Nevada uses an IDRP primarily, it has a limited rate-setting component. Nevada requires insurers to provide an upfront payment within 30 days of being billed if the OON provider had previously been in-network with the insurer. The payment is required to be “appropriate and reasonable” based on the previously contracted rates. The provider can still initiate the IDRP if it believes the payment does not meet that standard, or if the insurer does not make a payment within the 30 days. But this limits any advantage either party might gain from breaking an existing contract. Nevada’s IDRP is final offer, similar to those described above.[15]

In July, Georgia became the latest state to enact SMB protections for patients. Georgia is notable, as the legislation passed with broad, bipartisan support as well as with relatively unified support of the state’s insurers, hospitals, doctors, and patient advocates.[16] Georgia’s statute establishes an upfront payment of whichever is greater: (1) the median in-network rate for the medical care in question, in 2017, adjusted for inflation; (2) like Nevada, the previously contracted rate between the provider and insurer in cases where such a rate exists; or (3) an amount higher than either of those if the insurer deems it appropriate based on the circumstances of the case. Providers are then able to request an IDRP within 30 days of payment if they feel the payment is not appropriate. Georgia, like Texas, allows bundling of IDRP cases. Also, like Texas, Georgia allows a 30-day period for continued negotiations between the payer and provider after the request to go to IDRP has been made before the process begins. Georgia’s IDRP is a final-offer model, and the arbitrator is to consider physician training, education, and experience, while the losing party must pay all IDRP expenses. Additional criteria have yet to be outlined through rulemaking. Georgia has also, like New York, undertaken to enhance transparency as part of its SMB legislation, including the establishment of an all-payers claim database and annual reports on the outcomes of cases that go to IDRP.[17]

California’s SMB regime has been in place since 2017, so at least some perspective on its functionality is possible. Unfortunately, also like New York, those data are largely anecdotal or from surveys, and much of them are disputed. Additionally, while California’s approach might seem similar to both Georgia and New York on the surface, there are nuances that are important. California has two separate frameworks for addressing SMB payments to providers, one for OON emergency care and one for non-emergency OON care. In cases of OON emergency care, insurers are required to reimburse providers the “reasonable and customary rate,” effectively the UCR.[18]

In the case of non-emergency OON care at in-network facilities, insurers are required to reimburse providers at either 125 percent of the Medicare rate or the average contracted rate for the insurer in question in the region where the service was provided, whichever is greater. Non-emergency OON care is regulated by the California Department of Managed Health Care (DMHC), and the DMHC has an internal metric for determining the average contracted rate for each plan by region. If a provider feels the payment received is insufficient, it can apply to the DMHC to enter an IDRP. Providers, however, don’t have access to the DMHC database, so it can be difficult for them to know if the insurer payment meets the minimum standard. If the provider’s application to enter the IDRP is approved, factors to be considered in determining payment include: provider training, education, and experience; the type of service; and the fees normally charged by the provider as well as the prevailing provider rates in the geographic area. Providers can also include any information relevant to the economics of their practice or unusual circumstances in the case. The arbitrator can set payment at any amount, unlike in final-offer models, but California does allow for bundling of claims.[19] From the provider perspective, however, California’s IDRP is difficult to access. California requires providers to have exhausted insurers’ internal payment appeal process, then requires approval of the request to engage the IDRP by the DMHC, an added step most states do not have.

Providers and insurers differ as to the impact of California’s SMB law since it was enacted in 2017. The California Medical Association (CMA) has argued that the law reduces insurers incentive to contract with physicians. It maintains that physicians are being forced out of insurer networks, and that patient complaints about access to providers in the state have increased 50 percent.[20] Further, in a 2019 survey of California physicians conducted by CMA, 88 percent of respondents said they believed the law decreased provider networks, and 92 percent said it had reduced their leverage in negotiating contracts. The DMHC complaint data provides corroborating evidence, as patient complaints about access to providers have increased dramatically in recent years. Between 2014 and 2017, complaints related to access grew from 301 to 419, but 2018 there were 614 access complaints and in 2019 that figure nearly doubled to 1,216.[21] On the other hand, America’s Health Insurance Plans maintains that the number of physicians in-network in California has increased 16 percent since the law was enacted. Research from the USC Schaeffer Center for Health Policy and Economics published in late 2019 found a 17 percent decrease in the share of OON services. It also observed an increase in services delivered in-network.[22]

Currently the Michigan legislature is considering several pieces of legislation aimed at curtailing SMBs and adjudicating payment disputes between providers and insurers. While the details in the case of Michigan are something of a moving target, legislators seem to be circling around a proposal that appears similar to that of California’s on the surface, but which would deviate from the approaches taken by other states more recently. Michigan is considering upfront rate setting for OON care of 150 percent of the Medicare rate or the average in-network rate, whichever is greater. The Michigan legislation would establish a process where the provider could appeal the payment to the Michigan Department of Insurance and Financial Services if it maintains the insurer had miscalculated the correct payment based on the rate-setting proposal, and the department will determine the correct payment. The Michigan legislation would allow for a separate IDRP, but it is limited. In cases of emergency care, with complicating factors, the provider can seek payment from the insurer greater than the rate set by the statute, but only in cases where the insurer fails to meet network adequacy standards. As a result, the proposal under consideration looks like rate setting with an IDRP backstop, but in practice the IDRP appears to have little substance.[23]

Conclusion

There are two key takeaways that federal policymakers can glean from the experience of states in regulating SMBs.

First, despite the nuance described in the preceding pages, there is a substantial amount of consensus among the various state approaches: Three-fifths of states have undertaken measures to protect patients from SMBs (and there is consensus that patients are being well served in those states with comprehensive approaches to SMBs); over two-thirds of states regulating SMBs have sought to mediate payment disputes for OON services; and more than half of the states that have regulated SMBs have included some type of independent dispute resolution. In fact, the vast majority of states that enacted SMB laws within the last year—including Georgia, Virginia, Washington, and Texas—incorporate IDRPs.

Second, while some initial indicators are positive, more time is needed to assess the impact of these policies. Much of the data about these policies’ outcomes is disputed, but transparency around state regulations will be crucial to determining the impact of these policies on the various stakeholders, including the federal government and overall health care costs. Any federal action should prioritize ensuring data on outcomes are publicly available.

Most of the legislative proposals at the federal level regarding SMBs are in line with the state trend toward incorporating IDRPs as a way of mediating payment disputes, but policymakers have disagreed over whether to incorporate rate setting for initial payments. Providers have broadly opposed upfront rate setting in advance of IDRPs, while insurers have generally preferred some type of rate setting tied to median in-network rates. Providers’ concerns include whether setting a minimum, upfront payment can curtail the IDRP by weighting the process toward the government-set rate. Additionally, without transparency around how government-set payment rates are determined, providers may question their fairness. At the same time, not including upfront payment requirements could harm smaller practices and individual physicians who may not be able to survive financially without payment until an arbitration process has been completed. Ultimately, whether policymakers use rate setting, IDRPs, or a combination of the two, as they have recently seemed inclined, ensuring a fair process for both providers and insurers will be paramount.

Appendix 1.

| STATE[24], [25] | Holds consumers not liable for any portion of the bill beyond the in-network cost for: | Payment Standard? | Dispute Resolution Process? |

| AZ[26] | Emergency services by OON providers performed at an in-network facility.

Non-emergency care if the enrollee is not informed/does not consent. |

No | Yes; for claims exceeding $1000 (must be initiated by the enrollee). |

| CA[27], [28] | Emergency services provided by OON providers at both in-network and OON facilities.

Non-emergency care provided in an in-network facility. |

State provides a guideline for how much the insurer pays for an OON provider for emergency and non-emergency services. | Yes |

| CO[29] | Emergency services provided by OON providers at both in-network and OON facilities.

Non-emergency care provided in an in-network facility.

Requires disclosures of what services are OON. |

State provides a guideline for how much the insurer pays for an OON provider for emergency and non-emergency services. | Yes |

| CT[30] | Emergency services provided by OON providers at both in-network and OON facilities.

Non-emergency care provided in an in-network facility. |

State provides a guideline for how much the insurer pays for an OON provider for emergency and non-emergency services. | No

|

| DE[31] | Emergency services provided by OON providers at both in-network and OON facilities (post-stabilization is also protected as approved by the insurer). | State provides a guideline for how much the insurer pays for an OON provider for emergency services. | Yes |

| FL[32] | Emergency services provided by OON providers at both in-network and OON facilities.

Non-emergency care provided in an in-network facility.

Requires disclosure of what services are OON. |

State provides a guideline for how much the insurer pays for an OON provider for emergency and non-emergency services. | Yes |

| GA[33] | Emergency services provided by OON providers at both in-network and OON facilities.

Non-emergency care provided in an in-network facility.

Requires disclosure of what services are OON. |

State provides a guideline for how much the insurer pays OON professionals but not facilities.

|

Yes |

| IA[34] | Emergency services provided by OON providers at both in-network and OON facilities. | No | No |

| IL[35] | Emergency services provided by OON providers at both in-network and OON facilities; limited to a designated set of specialties.

Non-emergency care provided in an in-network facility. |

No | Yes |

| IN[36] | Emergency services provided by OON providers at both in-network and OON facilities (only applies to HMOs).

Non-emergency care provided in an in-network facility (Only applies to PPOs). |

No

|

No |

| MA[37] | Emergency services provided by OON providers at in-network facilities.

Non-emergency care provided in an in-network facility. |

No

|

No |

| MD[38], [39] | Emergency services provided by OON providers at both in-network and OON facilities.

Non-emergency care provided in an in-network facility.

Requires disclosure of what services are OON. |

State provides a guideline for how much the insurer pays for an OON provider for emergency and non-emergency services.

State has an all-payer rate- setting system in place for hospital-based services that is governed by the Health Services Cost Review Commission. |

No |

| ME[40] | Emergency services provided by OON providers at both in-network and OON facilities.

Non-emergency care provided in an in-network facility. |

State provides a guideline for how much the insurer pays for an OON provider for emergency and non-emergency services. | Yes |

| MN[41] | Emergency services provided by OON providers at both in-network and OON facilities.

Non-emergency care provided in an in-network facility when a participating provider is unavailable or without enrollee consent. |

No | Yes |

| MO[42], [43] | Emergency services provided by OON providers at in-network facilities. | No | Yes |

| MS[44] | Emergency services provided by OON providers at both in-network and OON facilities.

Non-emergency care provided in an in-network facility. |

No

|

No |

| NC[45] | Emergency services provided by OON providers at both in-network and OON facilities. | No

|

No |

| NH[46] | Emergency services provided by OON providers at in-network facilities; limited to a set of designated specialties.

Non-emergency care provided in an in-network facility; limited to a set of designated specialties. |

No | Yes; the NH insurance commissioner has exclusive jurisdiction. |

| NJ[47], [48] | Emergency services provided by OON providers at both in-network and OON facilities.

Non-emergency care provided in an in-network facility; requires a disclosure and expected cost of services. |

No | Yes; for amounts exceeding $1000. |

| NM[49], [50] | Emergency services provided by OON providers at both in-network and OON facilities.

Non-emergency care provided in an in-network facility. |

State provides a guideline for how much the insurer pays for an OON provider for emergency and non-emergency services. | No |

| NV[51] | Emergency services provided by OON providers at both in-network and OON facilities.

Non-emergency care provided in an in-network facility.

Requires disclosure of what services are OON. |

State provides a payment standard for facilities and providers that had a previous contract with the insurer. | Yes |

| NY[52], [53] | Emergency services provided by OON providers at both in-network and OON facilities.

Non-emergency care provided in an in-network facility. |

No | Yes; for amounts exceeding 120% of the usual cost. |

| OR[54] | Emergency services provided by OON providers at in-network facilities.

Non-emergency care provided in an in-network facility. |

State provides separate guidelines for how much the insurer pays for an OON provider for anesthesia and non-anesthesia claims. | No |

| PA[55] | Emergency services provided by OON providers at both in-network and OON facilities. | No

|

No |

| RI[56] | Emergency services provided by OON providers at both in-network and OON facilities.

Non-emergency care provided in an in-network facility. |

No

|

No |

| TX[57], [58] | Emergency services provided by OON providers at both in-network and OON facilities.

Non-emergency care provided in an in-network facility. |

No | Yes |

| VA[59] | Emergency services provided by OON providers at both in-network and OON facilities.

Non-emergency care provided in an in-network facility; limited to a set of designated specialties. |

No | Yes |

| VT[60] | Emergency services provided by OON providers at both in-network and OON facilities. | No

|

No |

| WA[61] | Emergency services provided by OON providers at both in-network and OON facilities.

Non-emergency care provided in an in-network facility; limited to a set of designated specialties. |

No | Yes |

| WV[62] | Emergency services provided by OON providers at both in-network and OON facilities. | No

|

No |

[1] http://www.health-law.com/newsroom-advisories-185.html

[2] https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/maps-and-interactives/2020/jul/state-balance-billing-protections

[3] http://www.legislature.mi.gov/documents/2019-2020/billengrossed/House/pdf/2019-HEBH-4459.pdf

[4] https://www.americanactionforum.org/research/the-national-implications-of-marylands-all-payer-system/

[5] https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/maps-and-interactives/2020/jul/state-balance-billing-protections

[6] https://nationaldisabilitynavigator.org/wp-content/uploads/news-items/GU-CHIR_NY-Surprise-Billing_May-2019.pdf

[7] https://nationaldisabilitynavigator.org/wp-content/uploads/news-items/GU-CHIR_NY-Surprise-Billing_May-2019.pdf

[8] https://isps.yale.edu/sites/default/files/publication/2018/03/20180305_oon_paper2_tables_appendices.pdf

[9] https://nationaldisabilitynavigator.org/wp-content/uploads/news-items/GU-CHIR_NY-Surprise-Billing_May-2019.pdf

[10] https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2019/11/05/776185873/to-end-surprise-medical-bills-new-york-tried-arbitration-health-care-costs-went-

[11] https://nationaldisabilitynavigator.org/wp-content/uploads/news-items/GU-CHIR_NY-Surprise-Billing_May-2019.pdf

[12] https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/maps-and-interactives/2020/jul/state-balance-billing-protections

[13] https://www.tdi.texas.gov/reports/documents/SB1264-preliminary-report.pdf

[14] https://www.tdi.texas.gov/reports/documents/SB1264-preliminary-report.pdf

[15] https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/maps-and-interactives/2020/jul/state-balance-billing-protections?redirect_source=/publications/maps-and-interactives/2020/apr/state-balance-billing-protections

[16] https://www.augustachronicle.com/news/20200615/state-senate-committee-approves-surprise-billing-legislation

[17] http://www.legis.ga.gov/Legislation/en-US/display/20192020/HB/888

[18] https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/maps-and-interactives/2020/jul/state-balance-billing-protections

[19] https://www.dmhc.ca.gov/FileaComplaint/ProviderComplaintAgainstaPlan/NonEmergencyServicesIndependentDisputeResolutionProcess.aspx

[20] https://www.cmadocs.org/newsroom/news/view/ArticleId/28116/CMA-urges-Congress-to-follow-New-York-s-successful-surprise-billing-model

[21] https://wpso.dmhc.ca.gov/Dashboard/ComplaintsIMRs.aspx

[22] https://www.brookings.edu/blog/usc-brookings-schaeffer-on-health-policy/2019/09/26/california-saw-reduction-in-out-of-network-care-from-affected-specialties-after-2017-surprise-billing-law/

[23] http://www.legislature.mi.gov/documents/2019-2020/billengrossed/House/pdf/2019-HEBH-4459.pdf

[24] https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/maps-and-interactives/2020/jul/state-balance-billing-protections?redirect_source=/publications/maps-and-interactives/2020/apr/state-balance-billing-protections

[25] https://www.healthsystemtracker.org/brief/an-examination-of-surprise-medical-bills-and-proposals-to-protect-consumers-from-them-3/

[26] https://www.azleg.gov/legtext/53leg/2R/summary/H.SB1064_04-25-18_CHAPTERED.DOCX.htm

[27] https://www.chcf.org/blog/surprise-medical-billing-hybrid-solution/

[28] https://dmhc.ca.gov/Portals/0/HealthCareInCalifornia/FactSheets/fsab72.pdf

[29] https://www.jdsupra.com/legalnews/new-colorado-surprise-medical-billing-46917/

[30] https://www.cga.ct.gov/2015/act/pa/2015pa-00146-r00sb-00811-pa.htm

[31] https://delcode.delaware.gov/sessionlaws/ga141/chp096.shtml

[32] https://www.flsenate.gov/Committees/BillSummaries/2016/html/1387

[33] http://www.legis.ga.gov/Legislation/20192020/194379.pdf

[34] https://www.legis.iowa.gov/docs/publications/BF/1069201.pdf

[35] https://www.ilga.gov/legislation/publicacts/fulltext.asp?Name=096-1523

[36] http://www.ciproms.com/2018/02/new-indiana-law-takes-effect-address-surprise-billing/

[37] https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/maps-and-interactives/2020/jul/state-balance-billing-protections?redirect_source=/publications/maps-and-interactives/2020/apr/state-balance-billing-protections

[38] https://www.psafinancial.com/2019/09/protecting-patients-from-surprise-medical-bills-benefit-minute/

[39] https://codes.findlaw.com/md/insurance/md-code-ins-sect-14-201.html

[40] https://www.mainelegislature.org/legis/bills/bills_128th/chapters/PUBLIC218.asp

[41] https://www.mnmed.org/getattachment/advocacy/protecting-the-medical-legal-environment/Legal-Advocacy/MMA_SurpriseBilling.pdf.aspx?lang=en-US

[42] https://insurance.mo.gov/consumers/health/managingcost.php

[43] https://www.senate.mo.gov/18info/BTS_Web/Bill.aspx?SessionType=R&BillID=73432653

[44] https://www.beckershospitalreview.com/finance/mississippi-residents-may-have-an-out-for-surprise-medical-bills.html

[45] https://blog.bcbsnc.com/2019/06/the-costs-of-surprise-medical-billing/

[46] https://www.nh.gov/insurance/media/bulletins/2019/documents/ins-19-015-ab-hb-1809-nh-balance-billing-and-network-adequacy-laws.pdf

[47] https://www.state.nj.us/dobi/division_consumers/insurance/outofnetwork.html

[48] https://www.insidearm.com/news/00044301-new-jerseys-out-network-medical-billing-l/

[49] https://www.nmlegis.gov/Sessions/19%20Regular/final/SB0337.pdf

[50] https://essentialhospitals.org/policy/four-states-start-2020-new-surprise-billing-laws/

[51] https://www.leg.state.nv.us/App/InterimCommittee/REL/Document/3653

[52] https://www.healthsystemtracker.org/brief/an-examination-of-surprise-medical-bills-and-proposals-to-protect-consumers-from-them-3/

[53] https://www.dfs.ny.gov/consumers/health_insurance/surprise_medical_bills

[54] https://www.oregon.gov/newsroom/pages/NewsDetail.aspx?newsid=2612

[55] https://www.legis.state.pa.us/cfdocs/legis/LI/consCheck.cfm?txtType=HTM&ttl=35&div=0&chpt=33

[56] https://sourceonhealthcare.org/states/rhode-island/

[57] https://capitol.texas.gov/tlodocs/86R/billtext/pdf/SB01264F.pdf#navpanes=0

[58] https://www.texastribune.org/2020/01/02/what-you-need-to-know-about-texas-new-surprise-medical-billing-law/

[59] https://lis.virginia.gov/cgi-bin/legp604.exe?201+sum+HB189&201+sum+HB189

[60] https://legislature.vermont.gov/statutes/fullchapter/33/065

[61] https://www.insurance.wa.gov/surprise-billing-and-balance-billing-protection-act

[62] http://www.wvlegislature.gov/wvcode/ChapterEntire.cfm?chap=16&art=29D§ion=4