Research

October 21, 2025

The Impact of Tariffs on Small Businesses

Executive Summary

- While the Trump Administration has implemented tariffs to pursue a wide range of policy objectives – from protecting domestic manufacturing to raising revenue to pay down U.S. debt – they have come at the cost of significant damage to U.S. businesses, particularly small businesses; the most damaging of these tariffs have been issued under the International Emergency Economic Powers Act, the legal vehicle for the administration’s “Liberation Day.”

- Small businesses are uniquely vulnerable to the administration’s protectionist trade policy due to their inherent disadvantages compared to large corporations, among them having fewer available resources to adjust supply chains, negotiate with suppliers, and address ever-changing trade rules.

- This research estimates the direct tariff costs for U.S. small businesses to be approximately $85 billion annually, while added regulatory hours, new trade compliance measures, and competitive disadvantages contribute billions in indirect costs.

Introduction

The Trump Administration has relied upon tariffs to achieve policy aims ranging from the creation of new manufacturing jobs to raising revenue to pay down the national debt. The most damaging of these tariffs have been issued under national security authorities such as the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA), the legal vehicle for the administration’s “Liberation Day,” and Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962. Small businesses are uniquely vulnerable to the administration’s IEEPA tariffs due to their inherent disadvantages compared to large corporations. These include having fewer available resources to adjust supply chains, negotiate with suppliers, and address ever-changing trade rules.

This research estimates the direct tariff costs for U.S. small businesses to be approximately $85 billion annually, but potentially as high as $100 billion. Small businesses also face challenges that are not factored into direct tariff cost calculations, which is why these figures are likely an underestimate of the overall impact of the Trump Administration’s trade policies. These additional factors include added regulatory hours, new trade compliance measures, higher customs broker fees, the end of a duty-free entry process, and competitive disadvantages compared to large businesses that contribute billions in indirect costs.

The State of U.S. Small Businesses

According to the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, there were roughly 34.8 million small businesses in the United States in 2024, accounting for 43.5 percent of gross domestic product and 45.9 percent of overall employment. While different organizations use various characteristics to define what constitutes a small business, the U.S. Small Business Administration generally defines a small business as an independent business with fewer than 500 employees. Small businesses can also be broken into subcategories based on employee counts; for example, a small business with fewer than 10 employees is referred to as a “microbusiness,” and a business with no employees other than the owner is referred to as a “nonemployer business.” A firm’s revenue may also be a factor in further sorting between U.S. companies. For the purpose of this research, however, small businesses will refer to those with fewer than 500 employees, unless otherwise noted.

Figure 1: Small Business Share by Size and Industry (2024)

Source: U.S. Small Business Administration

As figure 1 displays, the vast majority – 98 percent – of U.S. small businesses are nonemployer businesses or have between 1–19 employees, meaning millions of small businesses would be considered microbusinesses. The largest nonemployer business categories include professional services, transportation/warehousing, real estate, and construction. Nearly 60 percent of small businesses with 20–499 employees are in the industries of accommodation/food services, health care/social assistance, construction, manufacturing, and retail trade.

Small businesses participate in trade

Large multinational corporations are not the only U.S. businesses participating in international trade. Out of more than 240,000 U.S. importers in 2023, 97 percent, or 236,000, were small businesses. Known small business exports were valued at nearly $590 billion in 2023 and known imports were valued at close to $870 billion. It is worth noting that this is just the known trade value that can be directly traced to specific firms, meaning these values might be underestimating the total trade volume of U.S. small businesses. Assuming the ratios of known trade value to total trade value hold, small businesses may have been responsible for up to $975 billion in imports in 2023 and between $920 billion and $1 trillion in 2024.

Current small business sentiment

Current sentiment among U.S. small businesses is mixed, although it appears most remain optimistic. A survey by the Small Business & Enterprise Council reports that 67 percent of small business owners rate the current business environment as excellent or good and 34 percent say the U.S. economy is in good health, up from 29 percent in the first quarter of 2025. At the same time, 73 percent remain concerned about tariff policy, with 53 percent expecting negative effects alongside economic uncertainty. The uncertainty over U.S. tariffs is highly correlated with uncertainty over investment, employment, and profit margins, according to the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston. Net domestic investment by private domestic businesses is down from more than $1 trillion in Q1 2025 to $802 billion in Q2 2025, likely because of economic uncertainty.

U.S. Small Business Tariff Costs

This research estimates that the annual tariff cost for U.S. small businesses is likely between $85.2–$99.6 billion. This range depends on the tariff-calculation approach used, as well as the estimated 2024 trade volume attributed to small businesses. This research estimates the 2024 known and total trade values for small businesses based on 2023 U.S. census data from the Department of Commerce as well as 2024 trade data from the U.S. International Trade Commission.

Figure 2 shows the different cost estimates for the United States as a whole, small businesses including nonemployers and firms with an unknown number of employees (small business+), and strictly small businesses with 1–499 employees. Figure 3 further breaks down the tariff estimates based on the size of the firm, which is categorized by the number of employees.

Figure 2: Small Business Tariff Cost Estimate ($ Billions, 2024 Trade Volume Estimates)

|

Country-by-country Tariff Approach |

Overall Effective Tariff Approach |

|||

|

Known Trade Value |

Total Trade Value | Known Trade Value |

Total Trade Value |

|

|

Total Tariff Cost |

$247.3 |

$270.2 | $280.2 |

$314.7 |

|

Small Business+ |

$85.2 |

$93.5 | $88.7 |

$99.6 |

|

Small Business |

$60.2 |

$65.8 | $60.2 |

$67.6 |

Source: U.S. Census Bureau, U.S. International Trade Commission

The country-by-country tariff approach is a cost calculation that uses the specific tariff rate and import values for the top 25 U.S. trade partners and assumes a tariff rate of roughly 15 percent for the remaining countries. The overall effective tariff approach is a cost calculation that uses an average effective tariff rate of 17.9 percent applied to the aggregated import value of all U.S. trade partners. The known trade value refers to the portion of the total trade value that can be matched to specific companies and therefore is more accurately traced to small versus large businesses. The total trade value refers to the total U.S. import value, including imports that are not matched to particular companies. The total trade value can still be estimated for companies based on employer size given the percentage of known value to total value for each category. Although the ratios may have slightly changed, this approach gives a better depiction of the total tariff impact on U.S. businesses than just using the known trade value. Also worth noting for these calculations is the assumption that roughly 85 percent of imports from Canada and 84 percent from Mexico are entering duty-free as a result of United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement compliance.

Figure 3: Tariff Cost Estimate by Employer Size ($ Billions, 2024 Trade Volume Estimates)

|

Country-by-country Tariff Approach |

Overall Effective Tariff Approach |

|||

|

Known Trade Value |

Total Trade Value | Known Trade Value |

Total Trade Value |

|

|

Nonemployers/ Unknown Number |

$25.0 |

$27.7 | $28.5 |

$32.0 |

|

1–19 Employees |

$16.8 |

$18.3 | $16.2 |

$18.2 |

|

20–49 Employees |

$9.1 |

$10.0 | $8.9 |

$10.0 |

|

50–99 Employees |

$8.2 |

$8.9 | $8.4 |

$9.4 |

|

100–249 Employees |

$14.7 |

$16.0 | $14.7 |

$16.5 |

|

250–499 Employees |

$11.4 |

$12.5 | $12.0 |

$13.5 |

|

500+ Employees |

$162.0 |

$176.7 | $191.5 |

$215.1 |

Source: U.S. Census Bureau, U.S. International Trade Commission

According to the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, U.S. small businesses face approximately $202 billion in annual tariff costs. This estimate uses 2023 known trade volume data broken down by business size and country of origin. It assumes a straight passthrough of tariffs with no evasion, offsets, or other factors in the cost estimate calculation. For instance, a 25-percent tariff on $100 billion in imports would result in $25 billion in tariff costs. The Chamber also includes nonemployers and firms with an unknown number of employees in their estimate. This research’s tariff estimate factors in a tax-inclusive tariff rate, assumes a certain level of evasion takes place, and considers an income and payroll offset. It also differentiates the small business cost estimate from the small business+ for greater specificity.

Higher costs and higher prices

When faced with higher input costs, firms have two options: absorb the added costs or pass them along to consumers. A business might decide to absorb the cost, or “eat the tariff,” to preserve market share and maintain consumer demand for their products, resulting in a lower profit margin or requiring other cost-cutting measures. Alternatively, a firm may choose to raise prices to compensate for the tariffs, but at the risk of losing customers. To date, it appears most firms are choosing a combination of the two approaches, simultaneously raising prices and absorbing costs. Surveys and a Goldman Sachs analysis show U.S. companies have absorbed more than 60 percent of tariff costs as of June. Similarly, the U.S. Chamber of Commerce finds that 70 percent of small businesses have reported incurring higher costs and 60 percent have raised prices.

A report from the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta shows that small businesses are less able to pass through tariff-related costs compared to large firms. As a result, small firms expected sales to be nearly 9 percent lower compared to normal levels, while large firms expected sales to dip just 3.5 percent. Assuming small businesses are unable to raise prices to fully offset higher costs, they must plan to cover increased import prices and a costly shift in their supply chain. The ability to cover costs fully depends on the business’ cash flow, which is a reported issue for 45 percent of small businesses. Lacking a sufficient cash flow may push small businesses toward lenders for access to credit. The Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta also notes that only 27 percent of small importers have a high enough credit score for lenders to offer new lines of credit, compared to 70 percent of larger importers, leaving small businesses with fewer options.

The incoming employment data is also flashing warning signs for U.S. small businesses. The ADP National Employment Report for September 2025 showed that private employment among small businesses declined by 60,000 while large businesses increased by 33,000. This is the fifth-straight monthly decline for small businesses with 1–19 or 250–499 employees and fourth-straight decline for small businesses with 20–49 employees. This contrast between small and large firm performance may indicate that small businesses are reducing employment as a cost-cutting measure and supports the argument that the current environment is far more favorable to large firms than small firms.

Competing with big business

Whether small firms are stuck with higher input costs or begin to raise prices at higher levels relative to larger firms, they will be at a disadvantage compared to corporate giants that rely on pricing power, economies of scale, and tariff exemptions. One of the inherent advantages of multibillion-dollar firms is that they import and produce large quantities of goods, which provides negotiating leverage with suppliers and economies of scale. For example, between two contracts with foreign producers – one for 1 million units and one for 1,000 units – it is likely that a foreign producer would be more willing to renegotiate a lower per-unit price for a U.S. importer with a 1 million-unit contract than for an importer with, say, a 1,000 unit contract due to the sales volume, value, and consistency of that contract. Additionally, larger U.S. firms have their own economies of scale when manufacturing, which lowers unit prices relative to smaller manufacturing operations.

Another advantage large businesses have is greater political influence. Trade-related lobbying has spiked by close to 30 percent since the implementation of President Trump’s tariffs and several large firms have already received tariff exemptions. These exemptions result not simply from political lobbying but also from promising the administration significant domestic investments worth tens of billions of dollars. For example, companies such as Apple agreed to build manufacturing facilities in the United States, and therefore acquired tariff exemptions for many of their imports. Semiconductor companies such as Nvidia and AMD followed this playbook and agreed to pay a percentage of their sales in China to lower their tariff costs. The same trend holds for large, publicly traded companies in the pharmaceutical, energy, and technology sectors.

Small businesses are unlikely to have the financial capacity to invest billions of dollars in U.S. manufacturing or entire departments dedicated to lobbying efforts. As covered in a previous American Action Forum insight, firms that ask for specific exemptions for inputs may receive a competitive advantage when tariffs on similar products are left in place. Such exemptions also create barriers to entry for smaller firms with less access to capital, as they now face even greater costs to entry in a market dominated by large tariff-exempt corporations. Lobbying in favor of tariffs in a specific sector may also have downstream effects that negatively impact small businesses. For example, a 50-percent tariff on imported steel may benefit U.S. steel companies but numerous other companies will be hurt by higher inputs costs.

The Cost of Compliance

The direct cost of tariffs is not the only challenge small businesses must face. There is a host of trade-related regulations, indirect tariff burdens, and other compliance costs. For instance, regulatory compliance eats up time and labor that could otherwise be used for productive business activities, representing an opportunity cost. The cost of a compliance hour is estimated at between $30.66 and $100.

General regulatory burdens

According to the Trump Administration’s Office of Management and Budget’s website – reginfo.gov – there are 117 different information collection requests (ICR) specific to individuals or organizations participating in international trade. An ICR is a formal way to both gather data and ensure that there is regulatory compliance, in this case among global trade participants. Each ICR has a time burden and a certain number of responses, and some have an estimated cost burden that is publicly available. Looking at all active ICRs since 2019, there have been nearly 550 million responses totaling 18.1 million hours with an estimated cost burden of $53 million. When factoring in hourly opportunity costs – the estimated cost of ensuring compliance and filling out documents rather than performing other economic activities – an additional $556 million to $1.8 billion in costs are attributable to ICRs. Not all these regulatory burdens affect every type of business, although it is safe to assume that most costs are borne by small businesses since 90 percent of importers and exporters are considered small.

According to a report by the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, 51 percent of small businesses claim navigating regulatory compliance negatively impacted their growth in 2024. The same report noted that 69 percent of small businesses said they spent more per employee to ensure compliance than larger competitors, and only 59 percent said they relied on any outside legal counsel when faced with a compliance issue. The latter is concerning, as compliance or regulatory failures can result in thousands of dollars in fines and penalties or the seizure of imported goods.

Customs and border protection entry process

As tariffs are paid by the importing company, small businesses that import products or product components are liable for both paying tariffs and filing the appropriate paperwork, which can be substantial and costly to complete. Entry documents that may be required include an entry manifest, evidence of right to make entry, a commercial invoice, and packing lists, according to the Department of Homeland Security.

In response to President Trump’s frequently shifting tariff policy, many U.S. importers turned to customs brokers to help navigate compliance, increasing demand for their services, and driving skyrocketing broker costs. For example, the fees charged per Harmonized Tariff Schedule (HTS) code that independent brokers use to classify a shipment have typically ranged between $4–$7, but have increased by as much as $1–$5 over the past few months. This additional compliance cost could set small businesses back thousands of dollars a year, depending on the number and variety of products imported. This leaves small businesses with the choice between utilizing experienced brokers to avoid legal, regulatory, and compliance concerns or managing tariff paperwork on their own.

The end of de minimis

As of August 29, U.S. businesses and consumers will no longer be allowed to import products valued under $800 free from fees and duties. Alongside new tariffs, these packages will now be subject to greater scrutiny from Customs and Border Protection and will have to enter the country via a formal rather than informal entry process. President Trump’s executive order preemptively eliminated de minimis, which was set to end on July 1, 2027, as part of the One Big Beautiful Bill Act passed by Congress, and removes a trade rule on the books since the 1930s. In response to the end of de minimis, dozens of mail operators, postal services, and companies announced that they will suspend shipping to the United States due to the sheer amount of uncertainty surrounding how packages will be handled and the cost of tariffs.

Figure 4: Cost of Eliminating De Minimis for Small Businesses by Category ($ Millions)

|

Low |

Medium |

High |

|

|

Total |

$4,307 |

$8,875 |

$16,264 |

|

Administrative and Processing Fees |

$1,153 |

$5,190 |

$12,048 |

|

Newly Applied Tariffs |

$2,888 | $2,888 |

$2,888 |

|

Regulatory/Compliance Burden |

$265 |

$796 |

$1,327 |

Source: U.S. Customs and Border Protection, The Value of De Minimis Imports, U.S. Census Bureau, U.S. International Trade Commission

Building off past American Action Forum research, the cost of ending de minimis for small businesses is estimated to be between $4.3–$16.3 billion annually, with a middle-range estimate of $8.9 billion. The largest factor will be the cost of different administrative and processing fees, which can range from around $2 to more than $20 per package. Newly applied tariffs to these imports will cost small businesses approximately $2.9 billion annually, and the estimated regulatory burden is between $265 million and $1.3 billion depending on the added time it takes to fill out paperwork for each package.

This research estimates the 2024 de minimis trade value for countries based on prior years and uses a country-by-country approach when calculating tariff costs. Other costs are calculated by multiplying known package and shipment data by estimated costs per package. To find the portion absorbed by small businesses, this research multiplies the total costs by the calculated percentage of de minimis trade value that is attributed to small businesses.

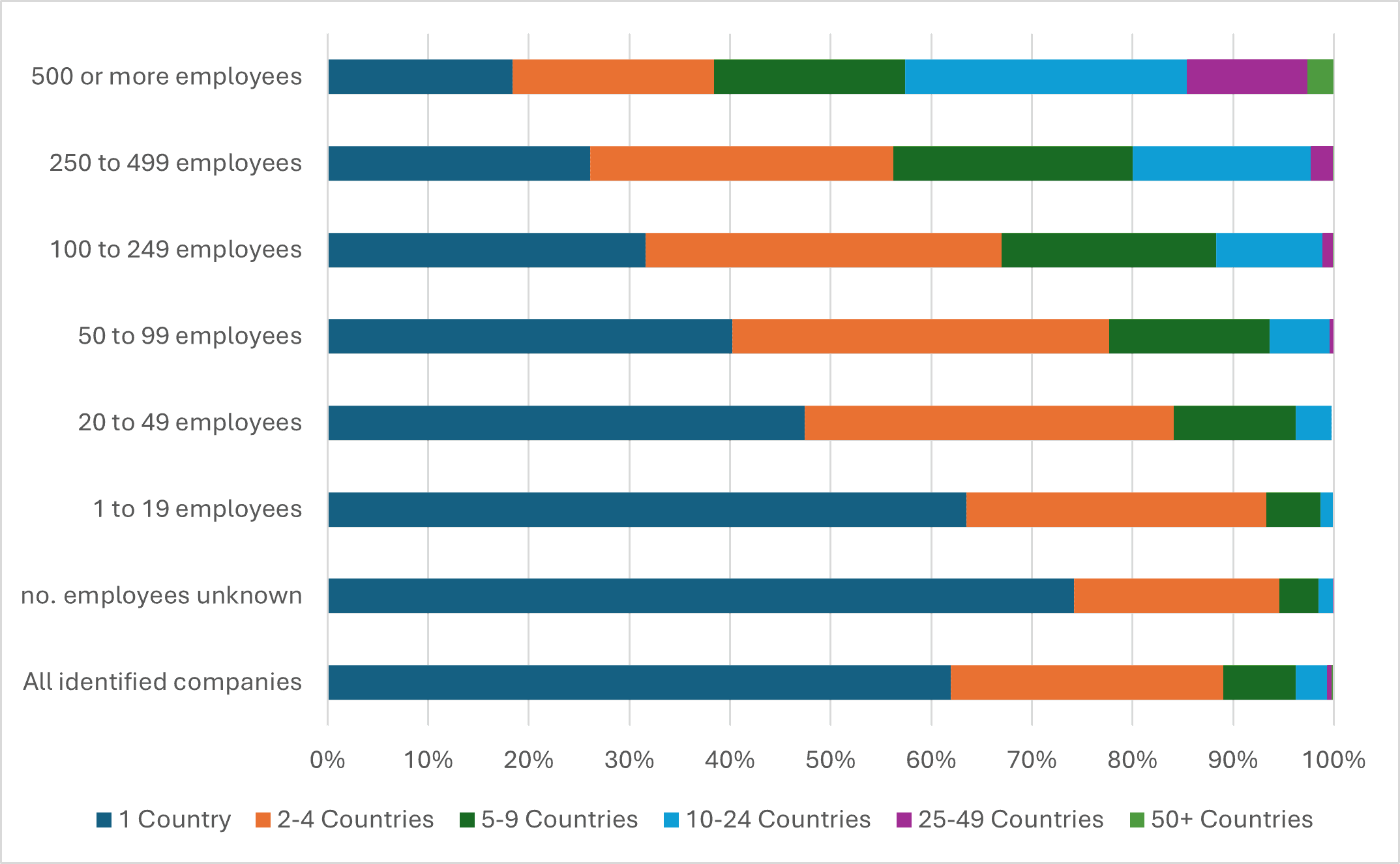

Small business supply chains

An additional challenge facing small businesses is the fact that their supply chains are not as diversified as large, multinational corporations. Most small businesses rely on just one supplier and import around two different products, indicating their supply chains are less complex and more concentrated than large businesses. Figure 5 displays different firm sizes and the percentage of each category that imports from a certain number of countries. It shows that small business importers rely primarily on one country for their imports, with 94 percent of businesses that have between 1–19 employees importing from four countries or fewer. As firm size increases, so does the number of countries on which a firm relies for imports. Figure 6 shows the known import value by firm size and the share accounted for by firms importing from a different number of countries. For example, 26 percent of all known import value comes from firms/importers that have 50 or more partner countries. By contrast, less than 1 percent of all importers have 50 or more partner countries, which demonstrates that most imports come from large businesses with complex supply chains.

Figure 5: 2023 U.S. Importers by Business Size and Number of Partner Countries

Source: U.S. Census Bureau

Figure 6: 2023 U.S. Known Import Value by Business Size and Number of Partner Countries

Source: U.S. Census Bureau *Some data unavailable to avoid business disclosures

Many small businesses have limited existing flexibility in their supply chains. Furthermore, the costs of finding a new supplier can be very high; it can take up to three years for the average importer to find a new supplier. The U.S. Chamber of Commerce also recommends that businesses negotiate with suppliers and attempt to establish long-term contracts, but small businesses with smaller order volumes may have limited negotiating power. Finally, many large companies are able to avoid some increased costs by stockpiling goods. With limited funding and storage capacity, this option also remains difficult for small businesses.

Conclusion

U.S. small businesses are uniquely vulnerable to the administration’s protectionist trade policy due to their inherent disadvantages compared to large corporations, among them having fewer available resources to adjust supply chains, negotiate with suppliers, and address ever-changing trade rules. This research estimates the direct tariff costs for U.S. small businesses to be approximately $85 billion annually, while added regulatory hours, new trade compliance measures, and competitive disadvantages contribute billions in indirect costs. In short, the administration’s tariffs are already having an outsized impact on U.S. small businesses, and the impact may intensify as the resources necessary to meet the tariff requirements dwindle.