Research

September 4, 2018

What About “Below the Fold” Regulatory Actions?

The Trump Administration has received a lot of attention for its high-profile actions repealing or revising past regulatory programs. In August alone, the administration released two major deregulatory proposals: freezing light vehicle fuel-efficiency standards, and replacing the Clean Power Plan. Under Executive Order (EO) 13,771, agencies are required to conform to a “regulatory budget,” and these new regulations, assuming they become final, will no doubt make up a large part of the deregulatory side of future budgets.

While EO 13,771 focuses on “significant” rulemakings – essentially expensive or novel regulations—hundreds of more mundane rules continue to churn in the background. These “below-the-fold” regulations may not grab the headlines, but their cumulative volume makes them valuable to assess along with the significant regulations. The amount of significant regulation has declined under the Trump Administration, but these more minor regulations have also seen a slowdown in overall volume – albeit at a less dramatic clip.

NONSIGNIFICANT RULEMAKING VOLUME

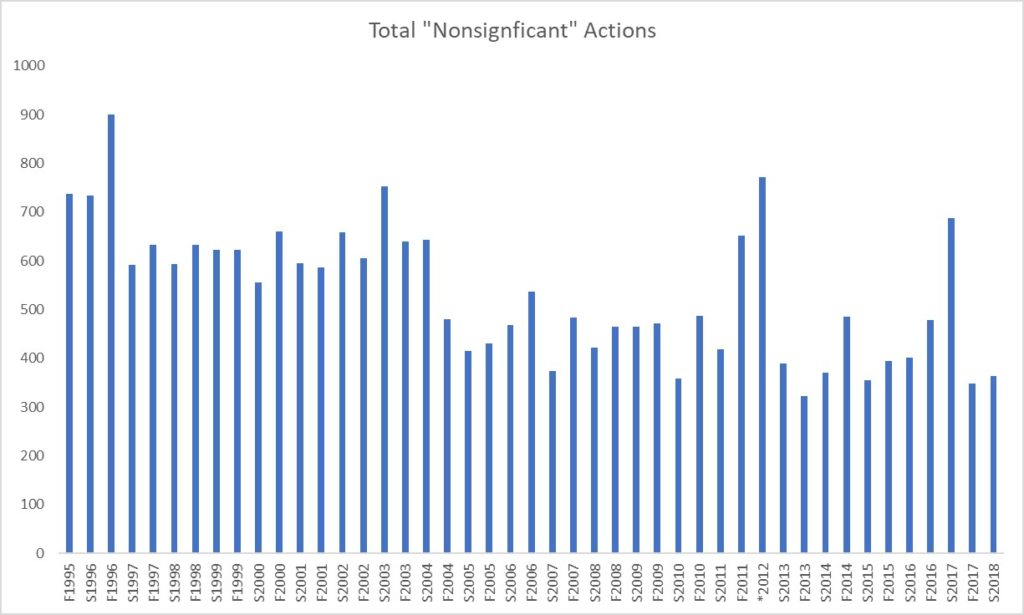

The following chart shows the total amount of “nonsignificant” completed actions found in each issue of the Unified Agenda going back to Fall 1995. The Unified Agenda is a document generally released twice a year, in the Spring and Fall, detailing agency plans for future rulemaking actions as well as recording each agency’s “Completed Actions” since the previous issue. The rulemakings in the chart do not meet one of the following for a “significant” rule, as laid out in EO 12,866:

- Have an annual effect on the economy of $100 million or more or adversely affect in a material way the economy, a sector of the economy, productivity, competition, jobs, the environment, public health or safety, or State, local, or tribal governments or communities;

- Create a serious inconsistency or otherwise interfere with an action taken or planned by another agency;

- Materially alter the budgetary impact of entitlements, grants, user fees, or loan programs or the rights and obligations of recipients thereof; or

- Raise novel legal or policy issues arising out of legal mandates, the President’s priorities, or the principles set forth in this Executive order.

These nonsignificant actions set the ground rules on such important tasks as: setting standards for avocado insurance, establishing the “Cape May Vinicultural Area,” and amending video conference procedures.

The two entirely Trump-era issues (Fall 2017 and Spring 2018) are among the lowest in overall volume at 349 and 364, respectively, but they are not the lowest levels recorded. The Obama-era Fall 2013 issue is the lowest, at only 323 such entries. The next closest numbers are 355 in the Spring of 2015, 359 in Spring 2010, and 371 in Spring 2014 – all Obama-era issues. Additionally, in 2012 there was only one issue of the Unified Agenda released in 2012. If you split that issue’s figure (771) in half, that yields roughly 386. Overall, the Trump record so far seems to be on the low end of the spectrum, but hardly a historical outlier.

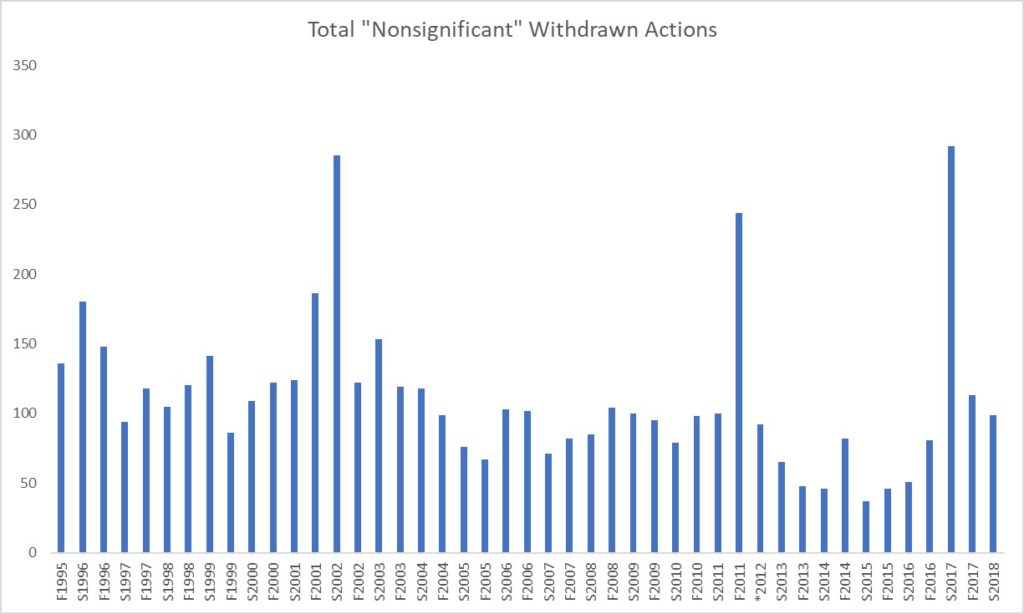

The Trump Administration’s deregulatory posture comes into sharper focus, however, when one considers withdrawn nonsignificant actions. Part of each Unified Agenda’s data on “Completed Actions” is a subsection on actions that agencies have withdrawn over that period. The following chart tracks trends in nonsignificant withdrawals.

In this category, the Trump-era entries include 113 and 99 such actions, respectively. The average amount of withdrawals across all Unified Agendas included above is 112. There are some interesting spikes across the years. Spring 2017 saw the highest level with 292 withdrawals. One expects that the regulatory freeze implemented upon President Trump’s inauguration was a major factor here. This withdrawal surge was still smaller than the 396 non-withdrawn actions over that period – many of which were likely “midnight regulations” at the end of the Obama term. There seemed to be a clear amount of regulatory housekeeping at the start of President Bush’s term, between the 186 in Fall 2001 and the 285 in Spring 2002 (fourth-most and second-most number of withdrawals, respectively). No such spike exists at the start of the Obama Administration, but rather in Fall 2011 (244 withdrawals). It is difficult to say for sure why the Obama Administration withdrew regulations when it did, but there was well-documented speculation that agencies held certain politically controversial rulemakings ahead of the 2012 election.

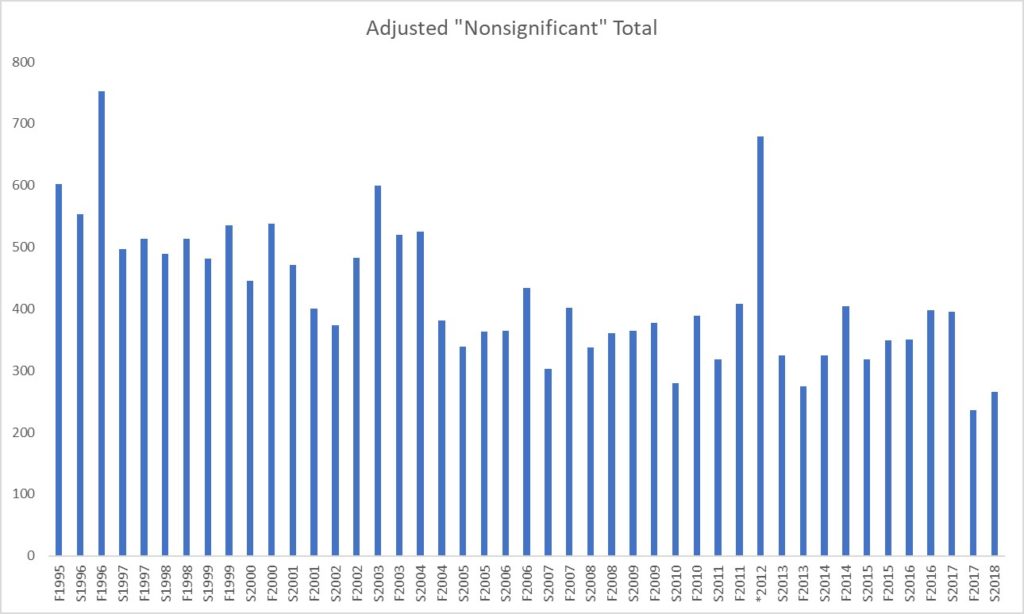

How does the level of non-withdrawal actions look for each year then? The following chart shows the in total completed actions for each Unified Agenda minus the withdrawals noted above.

With the volume of nonsignificant rulemakings adjusted for withdrawals, the two clear Trump-era periods are the lowest at 236 (Fall 2017) and 265 (Spring 2018). Certain Obama-era periods are not so far ahead, however, with 275 in Fall 2013 and 280 in Spring 2010. So while there’s little doubt the Trump Administration has sought to draw back the volume of regulatory activity, its record thus far on more mundane, routine regulations is not outside historical norms.

SIGNIFICANT RULEMAKING

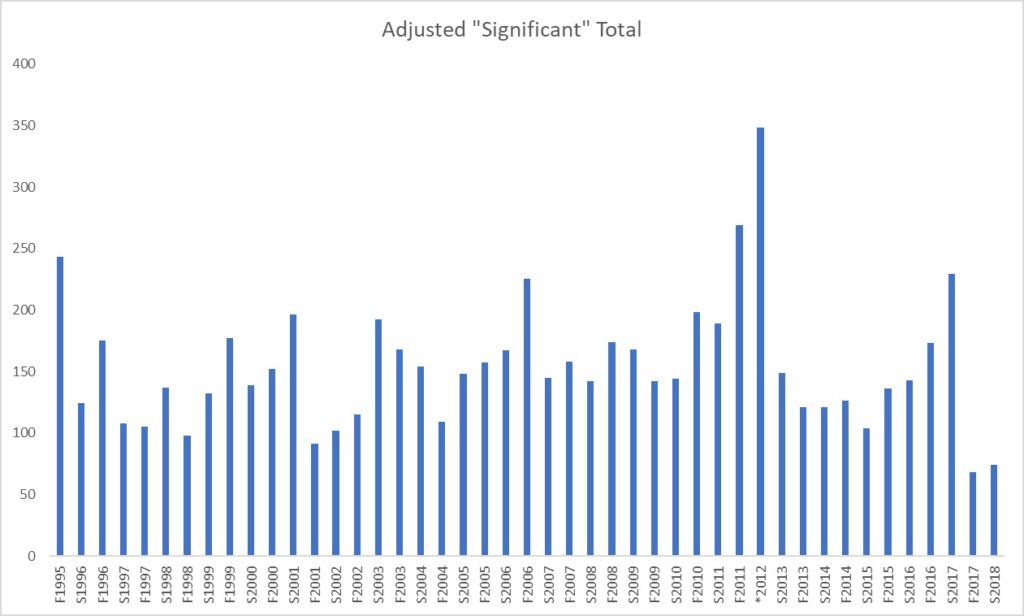

How does the subset of “significant” rulemakings compare? The following chart illustrates the total level of such actions, adjusting for withdrawals.

Of note, the three previous administrations each have one of the third-, fourth-, and fifth-lowest levels: 91 in Fall 2001 (Bush-), 98 in Fall 1998 (Clinton-era), and 104 in Spring 2015 (Obama-era). Still, Fall 2017 and Spring 2018 are clearly the lowest at 68 and 74, respectively. The two Trump-era periods are both less than half the overall sample’s average of 154.

This more dramatic drop is hardly shocking. EO 13,771 – and its subsequent guidance – directs agencies to cut two significant rules for each one that they create – the “one-in, two-out” rule. There will still be some rulemaking volume since a significant deregulatory action is still a rulemaking in-and-of itself (and counts toward the total rulemakings in these charts). Since each significant rule with new regulatory burdens generally needs commensurate deregulatory action under “one-in, two-out,” however, agencies may deprioritize marshalling scarce resources on new regulations unless there is a pressing need. Thus, there is at least marginal downward pressure on overall regulatory activity.

CONCLUSION

The Trump Administration has a clear and firm deregulatory mindset, and it has pursued many high-profile repeals and reforms. Yet while the largest rules receive almost all of the attention, hundreds of other rules are working through the pipeline that will eventually have an effect – however minor – on how entities or persons conduct business or interact with the government. The number of these rules has declined under the Trump Administration, too, but the trend here remains well within the realm of prior precedents.

METHODOLOGY

Reginfo.gov, the main website of the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs (OIRA), has digitally available versions of the Unified Agendas dating back to fall 1995. Using the search function for this data, one can examine overall trends in regulatory volume across five categories of “Priority”: Economically Significant, Other Significant, Substantive/Nonsignificant, Routine/Frequent, and Info./Admin./Other. This analysis deems those in the first two categories as “significant” and those in the remaining categories as “nonsignificant.” Withdrawn actions are those for which the “Timetable – Action(s)” section included a “Withdrawn” entry.