Testimony

June 2, 2020

Implementation of Title IV of the CARES Act

United States Senate Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs

*The views expressed here are my own and not those of the American Action Forum. I thank Thomas Wade for his insight and assistance.

Chairman Crapo, Ranking Member Brown, and members of the Committee, thank you for the privilege of appearing today to share my views on the implementation of Title IV of the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act. I wish to make three main points:

- A generous interpretation of publicly available data indicates that Treasury and the Federal Reserve have disbursed less than one percent of the $500 billion in emergency relief made available by Title IV of the CARES Act in the two months since passage of the Act.

- Treasury has provided no loans or loan guarantees under the powers granted it by Title IV to the intended recipients: airlines and businesses critical to national security. Although Title IV funding in theory backs five Federal Reserve emergency lending facilities, to date only one facility is operational that has purchased at maximum $1.8 billion in securities from capital markets.

- This slow pace stands in sharp contrast to lending made possible by other sections of the CARES Act and the other emergency lending facilities at the Federal Reserve. I can only speculate as to why, but it also suggests that there is considerable untapped economic support remaining from the CARES Act.

Let me discuss these in turn.

Title IV of the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act, signed into law on March 27, 2020, provides for $500 billion in financial assistance to eligible businesses, states, municipalities, and tribes as emergency relief for losses related to the ongoing coronavirus pandemic.[1]

The Title subdivides this $500 billion into three categories:

- $29 billion in loans or loan guarantees to passenger and cargo air carriers, and associated industries, of which $0 appears to have been spent;

- $17 billion in loans or loan guarantees for businesses critical to maintaining national security, of which $0 appears to have been spent; and

- $454 billion (including any amounts unused from the above) for loans, loan guarantees, and other investments in support of Fed emergency lending facilities, of which $195 billion can be considered “committed” to backing these facilities, but only $1.8 billion appears to have been spent.

The first two categories empower Treasury directly to make loans or loan guarantees to eligible parties in accordance with additional terms and conditions set out by the CARES Act, including restrictions on share buybacks and executive compensation.[2] The third category provides a potential source of funding for the Federal Reserve’s emergency lending facilities, with similar conditions applied.

A combined $1.8 billion of the $500 billion authorized by Congress in Title IV of the CARES Act has been spent as of the date of this testimony, two months after the CARES Act passed into law. This stands in comparison to the $513 billion in loan assistance[3] to small businesses administered by the Small Business Administration (SBA) in the form of Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) loans, as provided for by Title I of the CARES Act.

The remainder of this testimony will consider each category of Title IV relief in turn, followed by a comparative consideration of other Fed emergency lending and liquidity programs and the PPP for an overview of emergency relief as a result of the CARES Act as a whole and other efforts. In considering the implementation of Title IV, this testimony will cite at multiple points the findings of the first report[4] (the first Oversight Commission Report) of the Congressional Oversight Commission established by the CARES Act, published May 18, 2020.

Relief for Passenger and Cargo Air Carriers

The situation facing the airline industry today is unprecedented. The downturn in demand for commercial air transportation has been swift and dramatic. The International Air Transport Association predicts an almost 20 percent loss in worldwide passenger revenues, an astounding decline that would amount to more than $110 billion. Internationally and domestically, airlines have already cut routes, reduced jobs, and even shut down operations.

But things are tough everywhere. Hotels and restaurants are empty, Broadway has been shuttered, and the entire private sector is faced with a sharp liquidity crisis. In contrast to those industries, however, airlines are a key part of the supply chain. Even passenger flights are not just for passengers – they are the backbone of the cargo industry. Roughly a quarter of all cargo is transported on those same passenger flights that are rapidly being grounded. The health of the transportation sector – airlines in particular – is inextricably linked to the health of our nation’s economy as a whole.

A disruption of airline service would ripple through the supply chain, creating further economic harm beyond the recent drop in demand. Businesses – and vital businesses in particular – still need to receive goods that they can then sell to the public. Airlines help ensure they receive those goods.

To be sure, intervening in a market economy is fraught. But this is no “bailout” of bad behavior. The airlines were in good financial shape: They had been raising compensation for employees and investing in their business models. This isn’t bailing out bad behavior – and the moral hazard that engenders. It is throwing a lifeline of bridge finance to get past the pandemic and back to business, while continuing to support the broader economy.

Although Treasury has not released a detailed breakdown of funds disbursed directly to eligible airlines, the first Oversight Commission Report found that Treasury had not disbursed any of the $29 billion in funds available under this part of Title IV. As of the date of this testimony, there are no public data to suggest that this has changed. Airlines had a deadline of April 17 to apply for loans. The first Oversight Commission Report notes that Treasury did receive and is evaluating applications; it is frustrating that in the six weeks since no emergency loans or loan guarantees have been granted.

Relief for Businesses Critical to National Security

In addition to emergency relief directly for passenger and cargo airlines, all drafts of the CARES Act[5] included a carve-out specific to businesses critical to national security. Despite the fact that this clause was not a late addition to the CARES Act, the Act did not define this crucial term. It would be nearly two weeks before Treasury provided a definition setting out the intended beneficiaries of this relief in a set of questions and answers released on April 10.[6] Treasury required that applicants for this relief operate top secret military facilities or have the highest-rated priority contracts with the Department of Defense. This guidance has not been updated since.

Further, it was not until April 27, a month after the enactment of the CARES Act, that Treasury opened the online application system for businesses critical to national security to apply for relief under this section of CARES, and eligible businesses were only provided with five days during which to apply. Despite this, April 30 remarks by Undersecretary of Defense Ellen Lord indicate that 20 companies had applied to Treasury for relief as a business critical to national security.[7]

As with airline relief, the first Oversight Commission Report found that Treasury had not disbursed any of the $17 billion in funds available under this part of Title IV. As of the date of this testimony, there are no public data to suggest that this has changed; as above, it does not seem likely that this position would have changed given that the window for application closed on May 1. Why has Treasury not granted relief as a result of any of these applications given that Treasury has at this point had a month to evaluate any applications?

Support for the Federal Reserve’s Emergency Lending Facilities

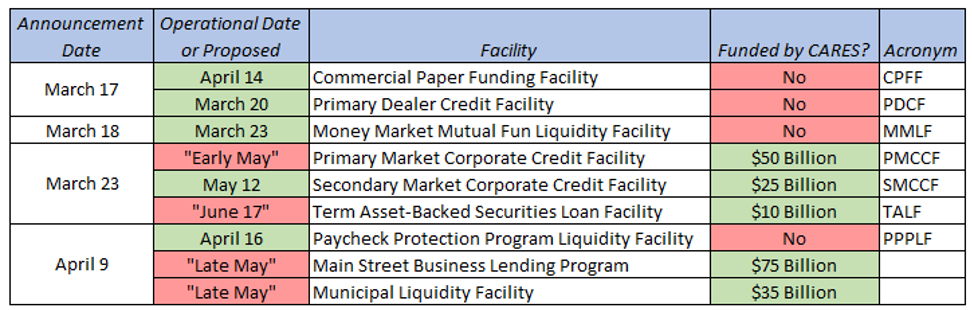

Since the onset of the coronavirus pandemic, the Federal Reserve has moved more decisively and more quickly in a matter of weeks than in the previous century of its operation.[8] In addition to cutting its key interest rate to zero percent and embarking upon a considerable round of quantitative easing, the Federal Reserve has introduced or reintroduced nine emergency lending facilities – some de novo and some created by the Federal Reserve in the 2007-2008 financial crisis under the emergency 13(3) powers created by the 1913 Federal Reserve Act.[9] Of these nine facilities, five have or will benefit from equity investments by Treasury using the $454 billion appropriated by the CARES Act. The status of these facilities is provided below.

Table 1 – Federal Reserve Emergency Lending Facilities

Source: The American Action Forum

A total of $195 billion as authorized by Title IV of the CARES Act has been committed by Treasury and the Federal Reserve to support five emergency lending programs. Before even considering the success of these five programs, however, it is immediately obvious that the residual $259 billion ($305 billion if the available funds to airlines and businesses critical to national security are also considered) remains unallocated. Two months after the passage of the CARES Act over half of the funds appropriated by Congress are not even committed, or available, to a Fed emergency program, even theoretically; this is funding that could support trillions of dollars of liquidity.

Of the five emergency programs nominally backed by CARES funding, only one program is operational as of the date of this testimony, the Secondary Market Corporate Credit Facility (SMCCF), which alongside the Primary Market Corporate Credit Facility (PMCCF) is designed to support the credit markets by providing liquidity for outstanding corporate bonds. The SCMMF in particular will only purchase exchange-traded funds (ETFs) with an investment-grade rating prior to the pandemic whose rating has since fallen to “junk” (at least BB-/Ba3). The number of firms to whom this applies is extremely small, with one analysis suggesting that only $50 billion in eligible high-yield bonds are available for purchase.[10]

The most recent Fed report to Congress on the status of the SMCCF was made before the SMCCF was functioning and as a result has no transaction data to report.[11] Although the first Oversight Commission Report notes that “on May 12 the [special purchase vehicle] began to make purchases of ETFs,” as of the date of this testimony the Federal Reserve has not made available to the public data specific to the volume of purchases by the SMCCF. In its weekly statistical release (H.4.1, Factors Affecting Reserve Balances), however, the Federal Reserve reported as of May 21, 2020, a $1.8 billion balance held by the Corporate Credit Facility special purchase vehicle through which the SMCCF and the PMCCF operate and will operate.[12] This $1.8 billion, it can be reasonably assumed, represents the balance sheet of the special purchase vehicle and therefore it can be deduced that the SMCCF has about $1.8 billion in ETFs, with funding presumably backed by Treasury.

Until the next report specific to the SMCCF is released by the Federal Reserve, the max that the $454 billion appropriated by Title IV appears to have disbursed appears to be $1.8 billion. Under the three sections in total of Title IV that appropriate $500 billion in emergency relief, at a generous interpretation, $1.8 billion, or less than one percent, appears to have been disbursed.

Going forward, this position will of course change. The proposed Main Street Lending Program will facilitate bank lending as much as $600 billion to businesses with under 15,000 employees or with 2019 annual revenues of up to $5 billion. Likewise, the Municipal Liquidity Facility will support as much as $500 billion in lending to state and local governments. Both programs, due to be operational very shortly, will in addition to the other Fed programs support trillions of dollars of liquidity. Both programs, however, designed to be key elements of the Federal Reserve’s emergency lending, will have at best only begun to operate two months after the enactment of the CARES Act.

Non-Title IV Lending and Relief

The focus of this hearing is Title IV of the CARES Act. It is interesting to note, however, the sharp difference between execution under Title IV and the Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) as administered by the Small Business Administration with the assistance of Treasury. The SBA has supported over $500 billion in lending to small businesses impacted by the pandemic. The PPP has proven so enormously popular and necessary as to require available funding to be increased after the CARES Act was signed into law. The program has justifiably come under some criticism, and in particular many questions remain outstanding as to the format and nature of loan forgiveness. Despite these flaws I have stated that the PPP is the best part of the CARES Act.[13] The SBA has facilitated the largest single support for the economy for the month of April. That such enormous sums were distributed to businesses in need at all, let alone so quickly, remains extraordinary.

This is not even the only relevant section of the CARES Act. Other sections provide the same industry-specific assistance specifically to the airline sector as seen in Title IV; the most recent figures show that Treasury has disbursed at least $12.4 billion[14] to 93 air carriers via the Payroll Support Program set up elsewhere in CARES.

Similarly, the Federal Reserve has acted with outstanding haste to attempt to balance negative forces in the economy. In addition to lowering the Fed Funds rate to zero percent and its quantitative easing efforts, the Federal Reserve acted with great speed to loosen capital restrictions on banks, making more capital available to businesses and individuals in need.[15] All of the Federal Reserve’s emergency lending facilities that are not backed in some way by Title IV are operational, and as of April 24 the Federal Reserve had provided $85 billion in funding to the market.[16]

Conclusions

It is clear that Treasury and the Federal Reserve are capable of decisive action both in the provision of direct loan support and by injecting capital into distressed markets. This makes the slow pace of execution under Title IV so striking.

The most charitable conclusion is that the Treasury and Federal Reserve are moving slowly to implement powers newly available to both. Broadly speaking, the Federal Reserve emergency lending facilities that are currently operational either are or have much in common with the emergency lending facilities employed during the previous financial crisis. The Federal Reserve has moved much more slowly on new facilities, most particularly the Main Street Lending Program, that represent such a significant departure from the ordinary business of the Federal Reserve.

It must be assumed that Treasury and the Federal Reserve have determined that the safest course for Title IV is to neither move fast nor break anything in such substantially new territory. At any rate, that such a significant portion of the CARES Act remains unused seems to suggest that the CARES Act can provide considerable additional support to the economy and that this unused authority should enter into the calculus governing any new pandemic-related legislation.

Thank you, and I look forward to your questions.

[1] https://www.banking.senate.gov/newsroom/press/cares-act-title-iv-summary

[2] https://www.americanactionforum.org/insight/financial-services-provisions-in-the-coronavirus-aid-relief-and-economic-security-cares-act-final-version/

[3] https://www.americanactionforum.org/research/tracker-paycheck-protection-program-loans/

[4] https://www.toomey.senate.gov/files/documents/COC%201st%20Report_05.18.2020.pdf

[5] https://www.americanactionforum.org/insight/financial-services-provisions-in-the-coronavirus-aid-relief-and-economic-security-cares-act-final-version/

[6] https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/CARES-Airline-Loan-Support-Q-and-A-national-security.pdf

[7] https://www.defense.gov/Newsroom/Transcripts/Transcript/Article/2172171/undersecretary-of-defense-as-ellen-lord-holds-a-press-briefing-on-covid-19-resp/

[8] https://www.americanactionforum.org/insight/timeline-the-federal-reserve-responds-to-the-threat-of-coronavirus/

[9] https://www.federalreserve.gov/aboutthefed/fract.htm

[10] https://www.advisorperspectives.com/commentaries/2020/05/26/the-feds-corporate-bond-buying-programs-faqs?topic=covid-19-coronavirus-coverage

[11] https://www.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/files/pmccf-smccf-talf-4-28-20.pdf#page=3

[12] https://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/h41/current/

[13] https://www.americanactionforum.org/daily-dish/in-defense-of-the-ppp/

[14] https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/treasury-implementing-cares-act-programs-for-aviation-and-national-security-industries

[15] https://www.americanactionforum.org/insight/timeline-the-federal-reserve-responds-to-the-threat-of-coronavirus/

[16] https://www.federalreserve.gov/publications/reports-to-congress-in-response-to-covid-19.htm