Testimony

May 24, 2023

Testimony on: Regulatory Burdens and Economic Growth

United States House of Representatives Committee on the Budget

* The views expressed here are my own and not those of the American Action Forum. I thank Dan Goldbeck for his assistance.

Chairman Arrington, Ranking Member Boyle, and members of the committee, thank you for the privilege of appearing today to discuss regulation and economic growth. I hope to make the following main points:

- The United States is in need of faster long-term economic growth;

- The burden of federal regulations has risen over time and is currently growing at an alarming rate;

- Excessive regulation is a headwind to long-run growth and exacerbates the near-term inflation pressures; and

- There are several strategies Congress could pursue to control the growth of regulatory costs.

Let me discuss each in turn.

The Need for More Rapid Economic Growth

Gross domestic product (GDP) per capita is a rough measure of the standard of living. During the final 50 years of the 20th century, GDP per capita rose on average at a 2.3 percent annual rate. At that rate, the standard of living doubles every 30 years. During a single working career, the standard of living could double, providing the path to each household’s personal version of the American dream.

But that growth has faltered in the 21st century, with average annual increases at an anemic 1.2 percent annual rate. As a consequence, it now will take 58 years for the standard of living to double. In short, the American Dream is disappearing over the horizon. Even more troubling than the recent economic past is the outlook. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projected in its April Budget and Economic Outlook that U.S. economic growth will average 2.0 percent over the period 2024–2033, suggesting a much lower growth in GDP per capita.

These distinct periods and trends should convey that the trend growth rate is far from a fixed, immutable economic law that dictates the pace of expansion, but rather is subject to outside influences – including public policy. Congress has an opportunity to commit to raising the long-term growth rate of the economy through permanent reforms to tax policy, energy policy, trade policy, immigration policy, and regulatory policy.

Faster economic growth will restore access to the American Dream, providing the resources for all manner of household consumption, business investment, and public-sector programs. All policy initiatives should be evaluated through the lens of economic growth.

Trends in Regulation and Regulatory Costs

To get a handle on how regulatory burdens affect economic growth, one must first ascertain what the regulatory landscape looks like. Thankfully, as part of its ongoing RegRodeo project, the American Action Forum (AAF) has a record of all rules with some measurable economic impact going back to 2005. The estimates logged in RegRodeo come directly from agency estimates provided in a given rule’s analysis. From 2005 to today, agencies have recorded cumulative totals of $1.5 trillion in regulatory costs and approximately 1.3 billion annual hours of paperwork. For perspective, the cumulative new regulatory costs imposed over the past 18 and a half years would represent roughly 6 percent of current U.S. GDP.

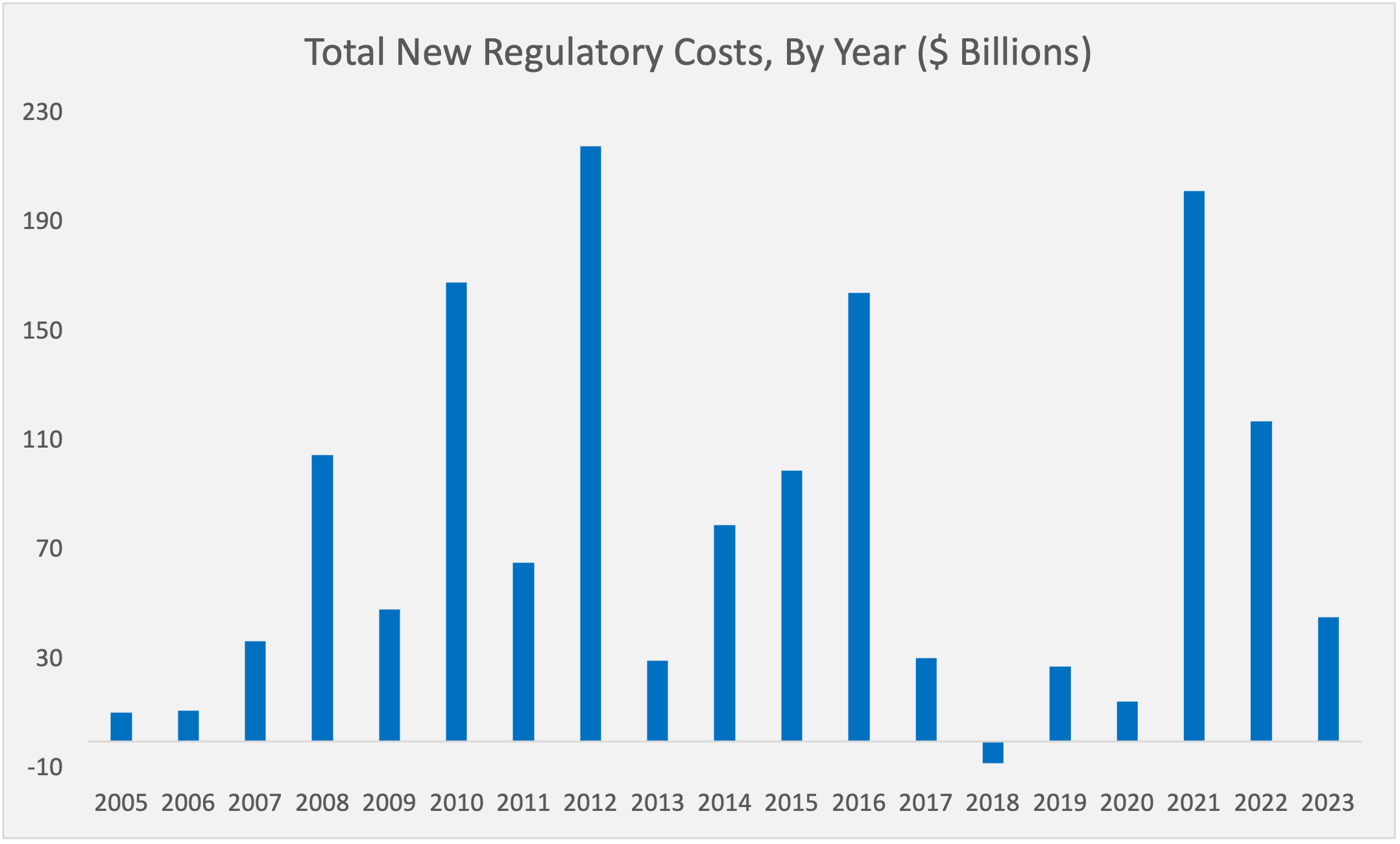

The cumulative picture, however, largely demonstrates the rough scale of regulation. There have been four different presidential administrations in power at some point during the span that RegRodeo covers, with both parties represented in two of those administrations apiece. Thus, it is important to examine the regulatory trends over time. The following graph charts the total costs imposed in a given year:

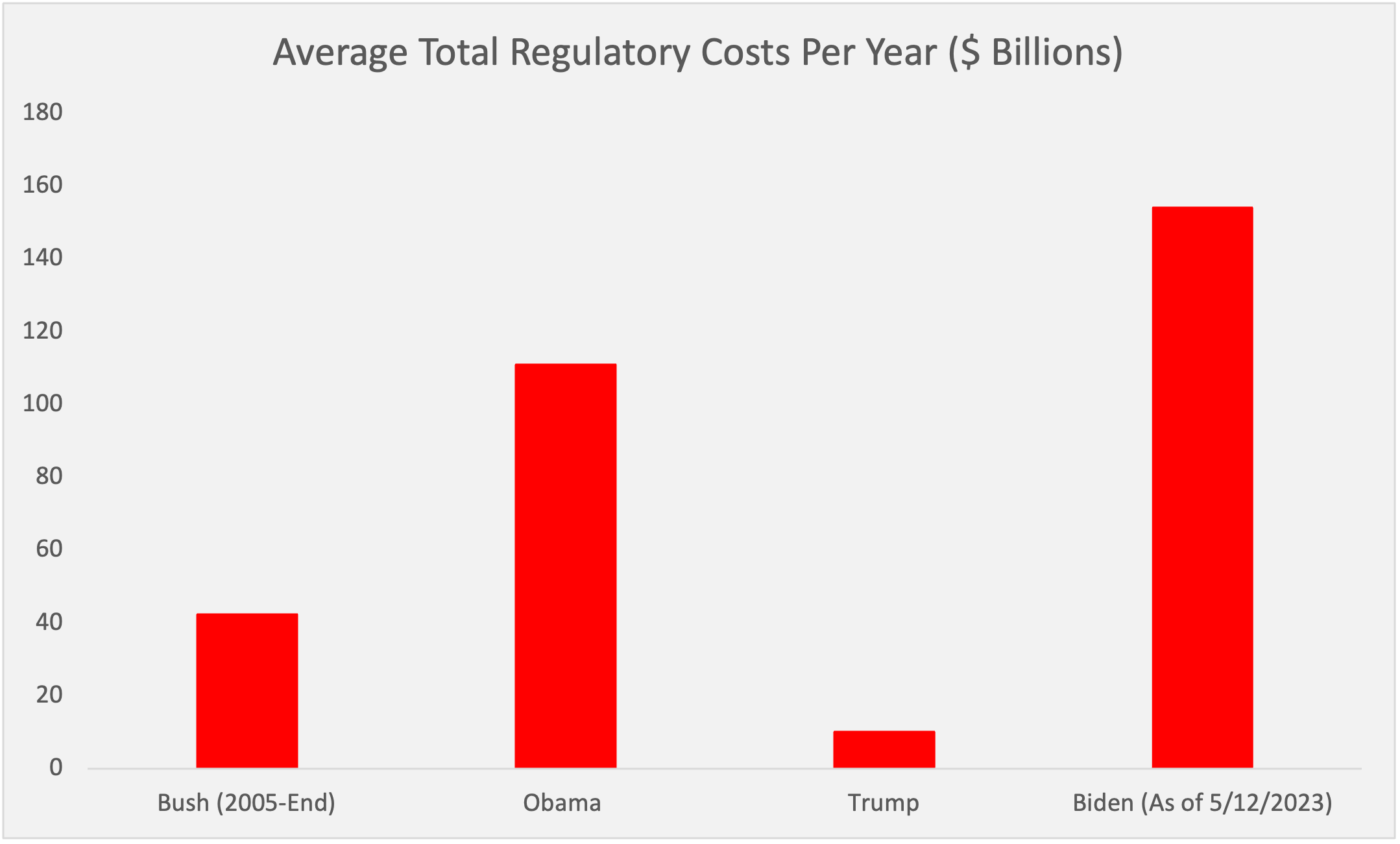

Granted, this only includes a partial sample of the Bush and (by necessity) Biden Administrations. It is nevertheless difficult not to draw some immediate conclusions regarding administration-to-administration trends. There is a noticeable difference in the magnitude of impacts imposed under Republican administrations (Bush and Trump) versus Democratic administrations (Obama and Biden). The following graph illustrates this point more finely by providing each the per-year average total costs imposed under a given administration:

It is also useful to examine some of the most consequential rules in order to better understand which industries are most heavily affected. The following table includes the 20 costliest rules recorded in RegRodeo:

| Regulation | Agency | Total Costs

($ Billion) |

| Revised 2023 and Later Model Year Light-Duty Vehicle Greenhouse Gas Emissions Standards | Environmental Protection Agency |

180.0 |

| 2017 and Later Model Year Light-Duty Vehicle Greenhouse Gas Emissions | Environmental Protection Agency |

156.0 |

| Defense Federal Acquisition Regulation Supplement: Assessing Contractor Implementation of Cybersecurity Requirements (DFARS Case 2019-D041) | Defense |

92.9 |

| Beneficial Ownership Information Reporting Requirements | Treasury |

84.1 |

| Importer Security Filing and Additional Carrier Requirements | Homeland Security |

56.0 |

| Light-Duty Vehicle Greenhouse Gas Emission Standards | Environmental Protection Agency |

51.8 |

| Federal Acquisition Regulation: Prohibition on Contracting With Entities Using Certain Telecommunications and Video Surveillance Services or Equipment | Defense |

42.9 |

| Control of Air Pollution From New Motor Vehicles: Heavy-Duty Engine and Vehicle Standards | Environmental Protection Agency |

39.0 |

| Transparency in Coverage | Health & Human Services | 34.5 |

| Definition of the Term “Fiduciary”; Conflict of Interest Rule | Labor |

31.5 |

| Greenhouse Gas Emissions Standards: Heavy-Duty Engines and Vehicles-Phase 2 | Environmental Protection Agency |

29.3 |

| Regulation Best Interest: The Broker-Dealer Standard of Conduct | Securities and Exchange Commission |

27.5 |

| Energy Conservation Program: Standards, Residential Refrigerators | Energy |

27.3 |

| Energy Conservation Standards for Residential Water Heaters | Energy |

26.6 |

| Asylum Application, Interview, and Employment Authorization for Applicants | Homeland Security |

24.0 |

| Disposal of Coal Combustion Residuals From Electric Utilities | Environmental Protection Agency |

23.2 |

| Positive Train Control Systems | Transportation | 22.5 |

| Energy Conservation Standards: General Service Fluorescent Lamps | Energy |

19.9 |

| Corporate Average Fuel Economy Standards for Model Years 2024-2026 Passenger Cars and Light Trucks | Transportation |

15.6 |

| Energy Conservation Standards for Commercial Air Conditioning, Heating Equipment | Energy |

15.0 |

Combined, these 20 rules involve total reported costs of nearly $1 trillion ($999.5 billion to be precise). In what is hardly a shocking development, energy and environmental regulations clearly involve the most dramatic regulatory costs, with half of this sample emanating from either the Environmental Protection Agency or the Department of Energy. Other areas of notable regulatory activity include defense, labor, health care, trade, and financial services.

Regulatory Costs and the Pace of Growth

There is no definitive estimate of the growth consequences of excessively costly regulation. Nevertheless, there is a growing literature examining the economic consequences of regulation. Van Reenen, Aghion, and Bergeaud (2023) analyze the consequences of a sharp increase in the burden of labor regulations on companies with 50 or more employees. Using panel data from France, they find that regulation is a headwind to innovation and growth: “Using the structure of our model we quantitatively estimate parameters and find that the regulation reduces aggregate equilibrium innovation (and growth) by 5.8% which translates into a consumption equivalent welfare loss of at least 2.3%, approximately doubling the static losses in the existing literature.”

Similarly, Armstrong, Glaeser, and Hoopes (2023) find that: “Consistent with regulation imposing net costs on firms, firms’ overall exposure to regulation negatively relates to their profitability and more regulated firms earn higher future returns.”

Finally, Dawson and Seater (2013) look at the economy as a whole and conclude: “We introduce a new time series measure of the extent of federal regulation in the U.S. and use it to investigate the relationship between federal regulation and macroeconomic performance. We find that regulation has statistically and economically significant effects on aggregate output and the factors that produce it–total factor productivity (TFP), physical capital, and labor. Regulation has caused substantial reductions in the growth rates of both output and TFP and has had effects on the trends in capital and labor that vary over time in both sign and magnitude. Regulation also affects deviations about the trends in output and its factors of production, and the effects differ across dependent variables. Regulation changes the way output is produced by changing the mix of inputs. Changes in regulation offer a straightforward explanation for the productivity slowdown of the 1970s.”

These findings are not surprising. Regulation imposes costs on firms, which compete with opportunities for innovation, capital investment, worker training, and productivity growth. At present, they also represent an additional supply shock that exacerbates inflation pressures. At present, however, Congress has little say in the evolution of the regulatory burden. Legislation would be needed to embed regulation reform as part of a growth strategy.

Options to Control Regulatory Costs

The Need for Further Legislative Reform

Any regulatory reform program that seeks to have a meaningful impact on aggregate growth trends will need to be structural and sustainable over the long haul. One point that is clear from the data discussed above is that any sort of policy seeking to roll back the growth of regulatory burdens that is primarily driven by the executive branch will likely have only transitory effects on the overall flow of new regulations. The only year recorded in RegRodeo data with net regulatory cost savings was 2018. For all the consternation regarding the Trump Administration’s deregulation policy under EO 13771, the cumulative impact of rulemakings during that administration added up to $40.4 billion in net costs.

There are several reasons for this. First, given that the policy emanated from an executive order, it had essentially no impact on the independent agencies operating outside of the White House’s purview. Such agencies produced roughly $41.4 billion in new regulatory costs over the Trump term. Second, outside of certain Obama Administration actions it could either rescind or indefinitely delay, all Trump-era deregulatory actions had to go through as typical notice-and-comment rulemakings. These actions take time and resources to produce and – as was occasionally apparent during the previous administration – are as vulnerable to judicial scrutiny as any cost-adding rulemaking. Finally, while the Trump Administration took on a primarily deregulatory posture, certain policy priorities of that administration – primarily in areas of trade and immigration – sought explicitly regulatory aims.

More important, however, is the simple fact that any executive-driven regulatory reform program is fundamentally at the whim of the incumbent executive. Even if the Trump Administration did not get to net-zero in regulatory burdens, the data discussed in the previous section clearly show that agencies were at least far more restrained than during either the Obama or current Biden terms. That restrained position went away as soon as President Biden assumed the office.

One key example that helps demonstrate the ephemeral nature of executive-driven actions came late in the Trump Administration. The Department of Health and Human Services put forward its “Securing Updated and Necessary Statutory Evaluations Timely” (SUNSET) rule that sought to set up a program under which the agency would conduct a comprehensive review of its regulatory stock and then allow outdated, unneeded, or duplicative provisions to expire. While the rule would have established one of the more notable federal-level regulatory reform frameworks in recent memory, the timing of its finalization made it vulnerable to repeal by the incoming administration.

Regulatory reforms that come as a result of legislative action are inherently more durable. While laws are, of course, repealed or amended by subsequent Congresses from time to time, the nature of the legislative process often makes it far more difficult to rescind laws than it would be for a given administration to repeal the actions of a preceding administration. Additionally, legislation that passes into law – especially in such politically contentious times – will likely need some degree of bipartisan buy-in to even become law. As such, a successful regulatory reform law will be insulated to some degree from political efforts to repeal it. The following section examines a few high-profile examples of regulatory reform proposals put forward in recent years that would have meaningful effects on economic growth trends.

Past and Current Reform Proposals Worth Consideration

REINS Act

One of the more notable reform proposals in recent years has been the “Regulations from the Executive in Need of Scrutiny” (REINS) Act. Most recently, it has seen a higher profile with the Limit, Save, Grow Act of 2023 including its provisions. The REINS Act would essentially be an updated Congressional Review Act (CRA). Whereas currently under the CRA Congress can elect to vote on a final rule’s repeal after it has been formally published, the REINS Act would require Congress to approve major rules (as determined by the Government Accountability Office) before finalization and allow the option for an approval vote for non-major rules. On one hand, the mandatory nature of major rule approval would add a currently absent level of political accountability to the rules with the greatest economic impact. Like the CRA, however, the REINS Act macro-level impact would be somewhat limited since a) it only addresses the regulatory picture in piecemeal fashion and b) the potential success of “approval” votes is inherently dependent upon the partisan make-up of a given Congress. Regulatory reform that has a more definitive impact on economic growth would need to be more systemic in nature.

SCRUB Act

One example from recent years that addresses regulatory burdens in a more comprehensive fashion is the “Searching for and Cutting Regulations that are Unnecessarily Burdensome” (SCRUB) Act. Mostly recently introduced in the , the SCRUB Act framework would establish a “Retrospective Regulatory Review Commission to conduct a review of the Code of Federal Regulations to identify rules and sets of rules that collectively implement a regulatory program that should be repealed to lower the cost of regulation,” with a goal of at least a 15 percent reduction in regulatory costs. Partially modeled on the Base Realignment and Closure commissions, the SCRUB Act would take the fact-finding effort out of the hands of partisan actors and attempt to conduct a system-wide review of the nation’s regulatory stock by placing the regulatory provisions flagged by the commission together for a single up or down recission vote. The SCRUB Act also establishes a rudimentary regulatory budget framework while the commission conducts its review in its “regulatory cut-go” provisions that require agencies to designate a rule in the review pool for repeal before they implement a new rule of similar costs.

Regulatory Budget

Perhaps the most high-profile regulatory reduction program in recent memory has been the “regulatory budget” program established under President Trump’s EO 13771. The regulatory budget expands upon the prototype of the SCRUB “cut-go” provisions to set up a more holistic, forward-looking reform structure. Broadly, a regulatory budget involves a mechanism by which agencies develop deregulatory actions that balance out – or exceed – new regulatory actions and establishes costs or savings goals across a given agency and/or the federal government writ large. In the years since the Trump Administration, there have been legislative versions of this general program introduced. Additionally, there have been state-level efforts in regulatory budgeting in recent years. Implemented properly, a regulatory budget program provides the most comprehensive reform of the regulatory process. It allows a given administration and/or the agencies under it to prioritize their regulatory – or deregulatory – aims. As discussed earlier, however, for a regulatory budget to have a real impact on macro trends, it needs to be durable across administrations since the transitory nature of politics leaves it vulnerable to shifting partisan whims.

Thank you. I look forward to your questions.