Weekly Checkup

February 1, 2019

A Dramatic Attempt to Lower Drug Costs

Late yesterday, the Trump Administration put forward a significant proposal on drug rebates. If you were confused after seeing health policy wonks in a tizzy over a proposed rule dropping, let me explain.

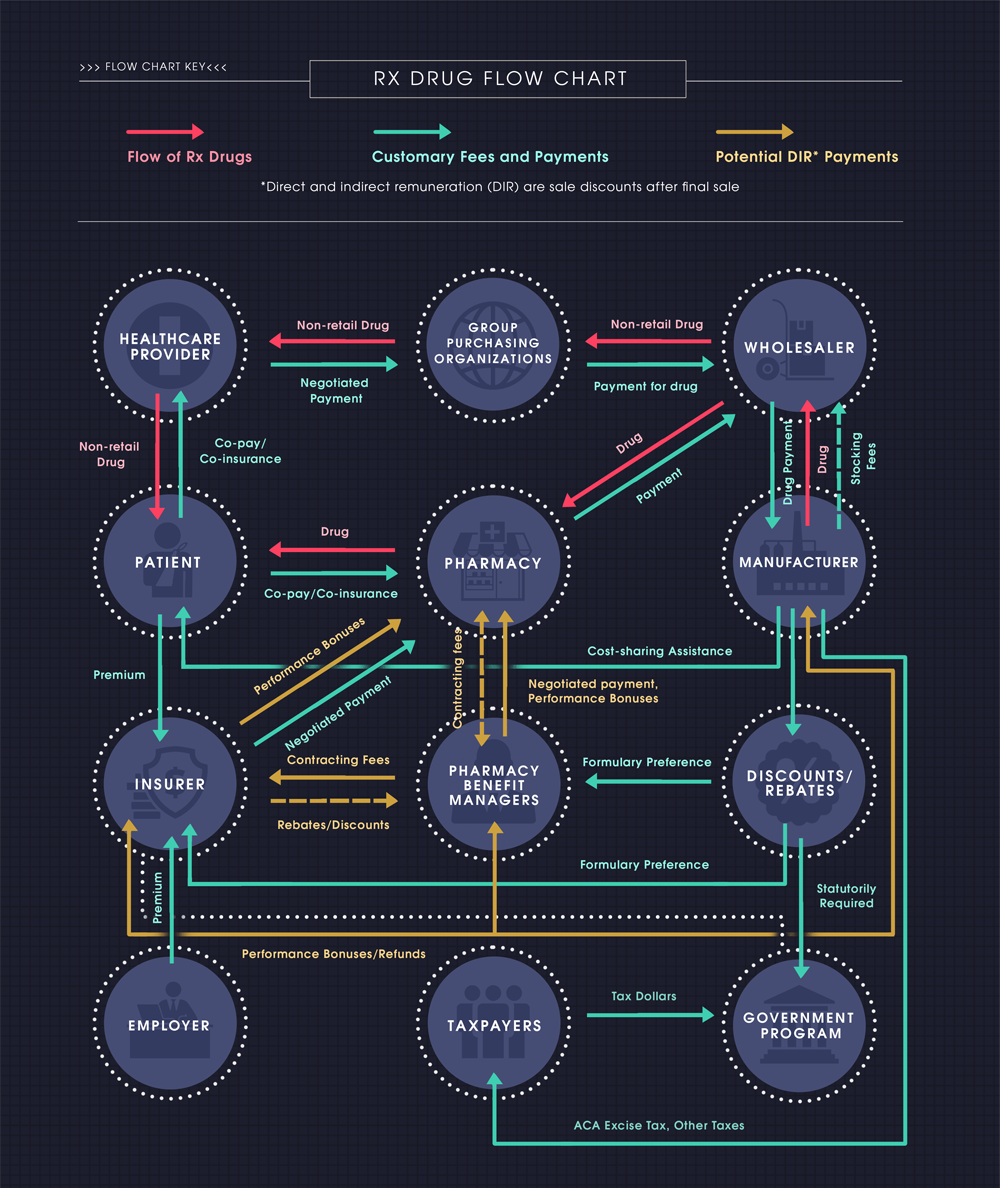

Yesterday’s proposal will result in significant changes to the current drug pricing and rebate structure, which is a bit of a labyrinth (see this week’s Chart Review below). The current system contains complicated and sometimes perverse incentives, which impact drug prices/costs.

Let’s cut to the chase. Under current law, drug manufacturers typically provide significant rebates for drugs provided at the pharmacy counter (averaging nearly 30 percent in Medicare Part D), especially for drugs with competing alternatives. These rebates are most commonly paid to pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) in exchange for preferred placement on the insurance plan’s drug formulary (i.e. the patient will be more likely to take that drug than another because it will be placed on a lower tier with lower cost-sharing). The PBMs, however, do not often share those rebates with patients when they pick up their medicine at the pharmacy counter. Instead, the rebates are typically used to hold down premium costs for everyone.

While many like to measure the success of health insurance programs by the premium amount, the premium is not necessarily the best metric. The easiest way to get low premiums is to have high out-of-pocket (OOP) costs—and that’s exactly what’s happening here. Using rebates on high-cost drugs to broadly lower premiums instead of passing them through to beneficiaries results in the (high-cost) sick subsidizing the (low-cost) healthy, which seems counter to the intent of an insurance product.

The proposed rule would change that practice, beginning next year. Drug rebates would no longer be allowed unless they are completely passed through to the patient at the point of sale. In other words, when a rebate is provided for a drug, the rebate will actually reduce the amount that the patient must pay at the pharmacy.

And yes, if you’re following, this shift would almost certainly lead to increased premiums for everybody. Those increases are likely to be minimal, however, as the cost increase would be spread across all beneficiaries. On the other hand, the reduced cost-sharing expenses that the highest-cost beneficiaries would see should outweigh those premium cost increases, resulting in a net benefit to patients. Of course, not all beneficiaries would benefit equally or even at all. Those patients with the highest costs would see the greatest benefit.

Further, to the extent this change reduces beneficiaries’ OOP costs, it should reduce the number of beneficiaries in Medicare Part D who reach the catastrophic phase, as OOP costs are used to determine when a patient moves from one phase of coverage to the next. AAF has written extensively on why keeping people from reaching the catastrophic phase is important and has proposed further changes to modernize the program and realign incentives even more.

Finally, while this rule only applies to Medicare Part D and Medicaid managed care plans, it is likely that this rule would have an indirect impact on the private market.

Chart Review

Christopher Holt, Director of Health Care Policy

While the newly proposed rulemaking from the Department of Health and Human Services—discussed above—would make some changes to this process, the infographic below (from this primer) displays the long and winding path that prescription drugs (and the money to pay for them) currently take from the manufacturer to patients.

Worth a Look

Axios: Medicare pitches 1.6% rate hike for private plans

New York Times: How One Woman Changed What Doctors Know About Heart Attacks