Weekly Checkup

September 11, 2020

Chronic Disease is More than a Health Care Challenge

The phrase “chronic disease” gets thrown around a lot in health policy circles, and there is widespread agreement that someone, somewhere, should do something about it. But often the discussion fails to go much deeper than that, and too often policymakers are focused on what to do once a person already has two or three or even five chronic conditions. A new primer from AAF’s Director of Human Welfare Policy Tara O’Neill Hayes and Serena Gillian looks at the trends around chronic disease and effectively defines the problem, but solutions will be more difficult.

A chronic disease is a condition that persists for at least a year, requires ongoing medical care, or interferes with daily activities. Hayes and Gillian note that an astounding 133 million Americans have at least one chronic disease, and roughly 30 million have five or more. The elderly, unsurprisingly, have high rates of chronic disease, but prevalence among them is not increasing beyond simple population growth. In other words, there are growing number of Medicare beneficiaries with chronic disease, but only because there are growing numbers of Medicare beneficiaries overall.

What’s really striking, however, is that 27 percent of U.S. children suffer from a chronic disease, and 6 percent have more than one. Hayes and Gillian write that in 1960 less than 2 percent of children experienced a chronic disease that negatively affected activities of daily living, but by 2010 that figure had increased to 8 percent. Of particular note is an increase in childhood obesity rates in recent decades. Today, 19 percent of children are obese, and juvenile diabetes rates increased by 23 percent between 2001 and 2009 alone. The prevalence of chronic disease is increasing across all age groups, but certainly the increases among children are particularly jarring.

While chronic disease may well be one of the defining public health policy problems of the moment—note how underlying conditions are a significant contributor to severe COVID-19 cases—its impacts are not limited to health policy. Hayes and Gillian go on to describe the economic ramifications of America’s exploding chronic disease challenge. They find that chronic conditions cost the United States $3.7 trillion annually, or 19.6 percent of gross domestic product. Some of this is direct costs related to hospitalization, medication, and emergency care, but indirect costs, such as lost productivity, limited educational attainment, and poor social well-being, also carry significant economic costs. When combined, the direct and indirect costs of chronic disease could cost the U.S. economy $42 trillion between 2016 and 2030. Chronic disease isn’t just a public health challenge; it’s one of the foremost economic problems facing the United States in the next few decades, particularly as an increasing number of Americans receive health care through federally financed programs.

Hayes and Gillian’s primer is chock full of useful charts and interesting data points, but my key takeaway is that policymakers will have to look at the challenge holistically, and with a view toward the long-term—never easy in Washington, DC. While we can and should do a better job of caring for those Americans with multiple chronic diseases, this is not a problem that will be addressed fundamentally in the hospital. We need to go back to the beginning and study the data. What is driving increased prevalence of these health challenges across various age demographics? For example, can we identify children who are at risk of developing chronic disease before they do, and what interventions can be undertaken to prevent or mitigate it? We won’t be able to win the battle against chronic disease if we don’t start fighting now to prevent future chronic disease, and we can’t afford not to win this fight.

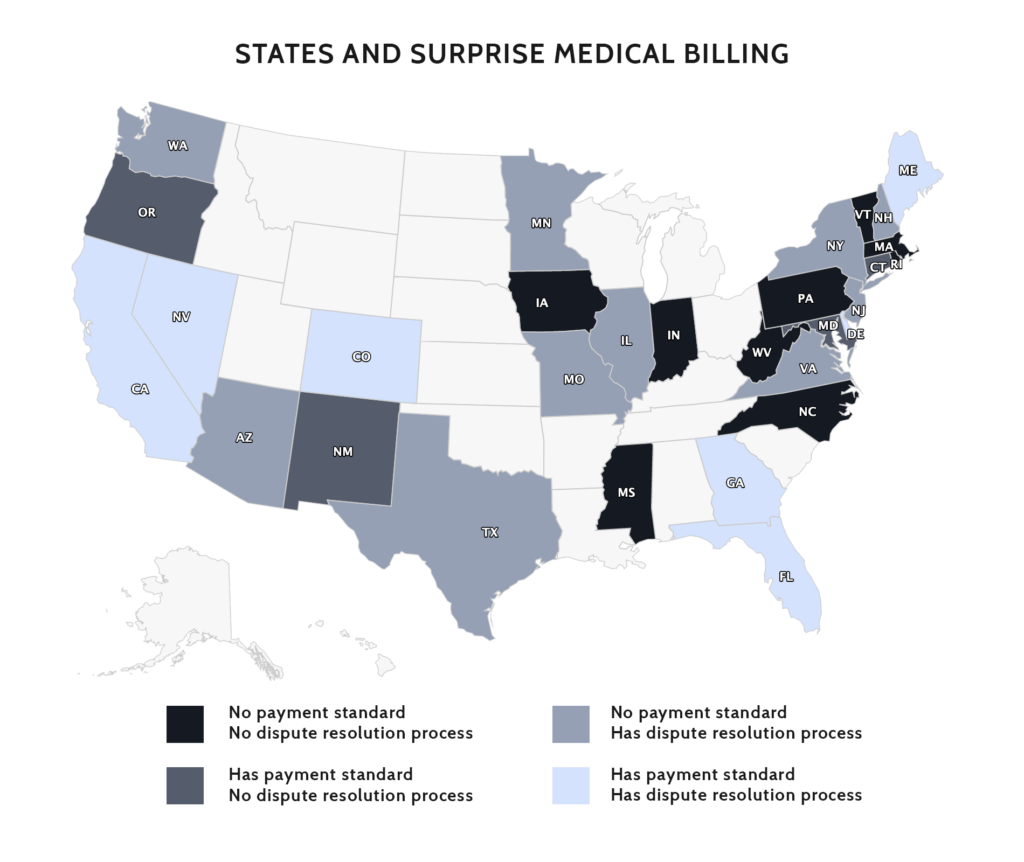

Chart Review: States and Surprise Medical Billing

In the absence of federal protections for patients from surprise medical bills, 30 states have implemented their own solutions, writes Christopher Holt in a recent paper. Though there is variation among state approaches and their relative effectiveness, there is also a striking amount of similarity in their content and design. In broad strokes, there are four categories of response that state have taken to address provider payment for surprise bills: (1) do nothing and leave payers and providers to fight it out; (2) rate setting; (3) independent dispute resolution process (IDRP); and (4) combine options 2 and 3 by establishing up-front minimum payments, while also providing an IDRP that providers can access under specified circumstances. Both the experiences of states as they have implemented surprise medical bill solutions, as well as the consensus that is forming around recent state initiatives, can inform the efforts of federal policymakers.

Worth a Look

Wall Street Journal: Ground Zero Workers With Chronic Conditions Get Hit Hard by Covid-19

Kaiser Health News: Obamacare Co-Ops Down From 23 to Final ‘3 Little Miracles’