Weekly Checkup

June 1, 2018

Evaluating “Right-to-Try”

During this year’s State of the Union address, President Trump called on Congress to pass “right-to-try” legislation. Congress responded, and this week the president signed the legislation into law. For a White House that has at times struggled to motivate Congress to tackle its agenda, this week’s bill signing is a clear win on process. The substantive effect of the legislation, however, is a bit harder to determine.

What is right-to-try? The basic concept is that terminally ill patients who have exhausted all approved treatments for their condition should be able to elect to receive experimental treatments that have not yet been approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). The FDA’s drug approval process is a long and arduous one by design. The whole reason for the FDA’s role in approving medical treatments is to ensure that the treatments sold to American patients, often at a tremendous cost, deliver on their promises. The process further seeks to verify that the positive effects of those medications outweigh the negative ones.

But this process takes time, and the importance of ensuring safe and reliable medical treatments for the nation as a whole can be unpersuasive to an individual who has run out of other options. And so, for decades, the FDA has operated a “compassionate use” program by which patients with limited remaining treatment options can apply for approval to receive experimental treatments. Proponents of right-to-try argue that this program is insufficient and that patients should be able to bypass the FDA and go directly to drug developers for access to treatments that are still under review.

What effects will the new right-to-try law have? The long-term impact isn’t entirely clear. First, it’s not as if FDA was in the habit of denying these requests before—most are approved, so it’s not obvious that allowing patients to bypass the FDA will dramatically increase the number of patients who gain access to experimental treatments. Second, pharmaceutical companies still have discretion to provide the medication. It’s not a forgone conclusion that companies will be eager to distribute unapproved medication without the imprimatur of the FDA’s approval. Finally, it’s worth noting the importance of the clinical trial process, which depends on patient participation. If right-to-try ends up allowing large numbers of patients to bypass the clinical-trial process, the strength of the standard channels for medical innovation could be weakened.

The new right-to-try law could benefit some patients—although how many is unclear—but it could have some negative consequences as well. Both possibilities are important to keep in mind.

Chart Review

Ben Gitis, Director of Labor Market Policy

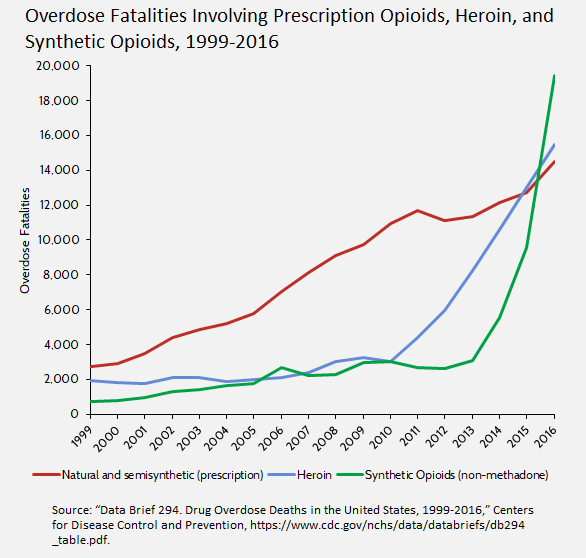

With opioid-related deaths and government efforts to combat them regularly in the news, AAF recently released a study of the kinds of opioids—prescription, heroin, and synthetic—involved in fatalities. As the chart below shows, the number of opioid-related deaths has risen for all kinds of opioids, but illegal synthetic opioids and heroin have accelerated most dramatically. The acceleration in overdose fatalities involving synthetic opioids and heroin corresponds to efforts to restrict prescriptions.

Worth a Look

Reuters: Another antibiotic crisis: fragile supply leads to shortages

Health Affairs: Precision Medicines Have Faster Approvals Based On Fewer And Smaller Trials Than Other Medicines

Wall Street Journal: Injured in Training or Injured in Combat? It Makes a Big Difference in Vets’ Access to Care