Weekly Checkup

August 5, 2022

It’s Not a Negotiation When They Have a Cudgel

The reports of Build Back Better’s death have been greatly exaggerated; it turns out it just needed a quick name change (it’s been rebranded as the Inflation Reduction Act, or IRA). Last week, President Biden was gifted a badly needed win by Senator Joe Manchin (D-WV), and the left are jumping for joy. While my colleagues at AAF have explained the follies of the IRA’s tax and climate provisions, this column focuses on the drug pricing “negotiation” provisions. A quick review of how a negotiation typically works: A buyer attempts to get the price as low as possible, the seller attempts to get it as high as possible, and they usually meet somewhere in the middle. Failing that, both parties walk away and accept the opportunity cost of not making a deal. Humans have been negotiating this way since we figured out how to make things other humans wanted.

What the IRA proposes for drug pricing is not a negotiation. The “negotiations” start with a statutory ceiling called the “maximum fair price” for drugs that have been approved for less than 12 years (“short-monopoly drugs”) of 75 percent of the average manufacturer price (AMP); for drugs approved between 12–16 years prior to being selected (“extended monopoly drugs”), that drops to 65 percent; and for drugs that have been approved for 16 more years (“long-monopoly drugs”), the ceiling plummets to 40 percent of the AMP. Depending on certain calculations specified in the legislation, the maximum fair price for Part B and Part D drugs could go even lower than those percentages. If manufacturers refuse these terms, they will face a decision: Pay an excise tax of up to 95 percent or pull out of the U.S. market entirely. In fact, the 95 percent excise tax doesn’t factor in the full effect of how the taxes are calculated; according to the Tax Foundation, it could actually reach up to 1,900 percent.

That’s not a “negotiation.” That’s the government holding a club and telling drug manufacturers to take it or leave it. Drug manufacturers cannot counter with an offer higher than specified in statute, and if their drug is selected by the secretary of Health and Human Services, they cannot back out of the “negotiations.” There is no opportunity for a fair negotiation between parties as the leverage the federal government would wield far exceeds that of drug manufacturers.

Should this become law, we will see one of two outcomes: The U.S. market will lose some drugs entirely, or U.S. drug manufacturers will significantly reduce their investments in research and development. Many on the left like to mock the latter as a “theoretical” argument, but it has happened before. Up until the 1990s, Europeans outpaced the United States in research and development investments. Then, in those years, European governments started adopting price control policies. By the end of the decade, the United States had surpassed Europe in drug research and development. The global dominance of an entire industry was determined by who had the better regulatory scheme for drug pricing. Stop calling the IRA’s drug pricing provisions a negotiation and recognize what they really are: an innovation-killing price control scheme.

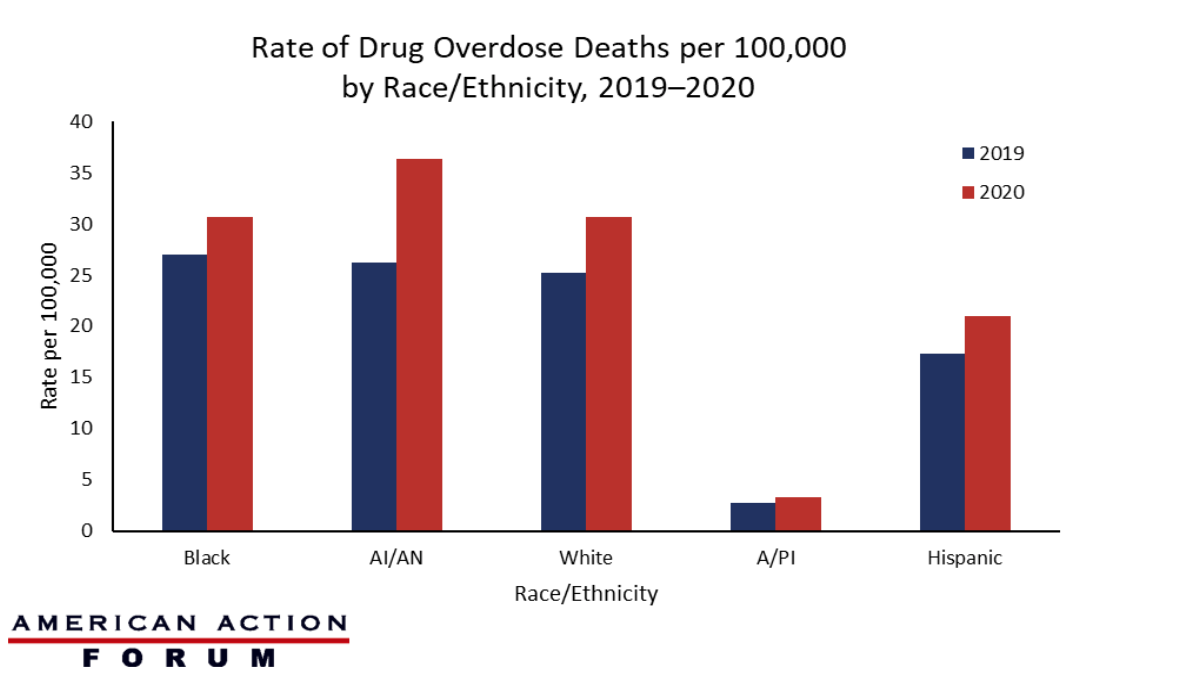

Chart Review: Rate of Drug Overdose Deaths by Race and Ethnicity, 2019–2020

Evan Turkowsky, Health Care Policy Intern

On July 22, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) released its report on drug overdose deaths from 2019–2020, the last year of available information. The report, which used data from the State Unintentional Drug Overdose Reporting System (SUDORS) from 25 states and the District of Columbia, showed a 30 percent increase in overdose deaths. The COVID-19 pandemic and the ensuing disruption in access to prevention, treatment, and harm reduction services likely contributed to an increase of nearly 27,000 drug overdose deaths in 2020. The chart below shows the rate of drug overdose deaths per 100,000 among different racial and ethnic groups in the United States. The “relative change” increases, which represent change based on different population totals, were highest from 2019–2020 among Blacks and American Indian/Alaskan Natives (AI/AN) at 44 percent and 39 percent, respectively. Among Whites, the relative change increased by 22 percent during the same period. With the smallest represented population (455 surveyed), Asian/Pacific Islanders (A/PI) showed the same relative change increase—22 percent—as Whites, who had the largest represented population (48,546 surveyed). Hispanics also demonstrated a similar relative change (21 percent). The findings in this report highlight the increasing impact of the overdose crisis across all races and ethnicities.

Data Source: The CDC and SUDORS