Insight

November 30, 2025

Inflation Reduction Act IPAY 2027 Maximum Fair Prices Have Been Published

Executive Summary

- The Trump Administration has published the maximum fair prices for covered drugs in the Medicare Drug Negotiation Program for initial price applicability year 2027; these 15 drugs in Part D were selected because of either high program spending or high beneficiary utilization.

- The administration’s touted $12 billion in savings (an approximately 44-percent reduction in net Part D spending if the prices had been in place for 2024) are nearly double the initial year of savings under the Medicare Drug Negotiation Program.

- While the savings seem significant, further analysis of the announcement identifies calculated inefficiencies, an overrepresentation of benefit, and the continued lack of evidence that any savings will truly materialize in Part D.

Introduction

On November 25, 2025, the Trump Administration announced the latest round of negotiated drugs under the Medicare Drug Negotiation Program established in the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA). The initial price applicability year (IPAY) 2027 announcement marks the second major wave of Medicare drug price negotiations, extending negotiated “maximum fair prices” (MFPs) to 15 high-spend or high-utilization Part D drugs starting January 1, 2027. These drugs accounted for roughly $42.5 billion in gross Part D spending in 2024 – about 15 percent of total program drug costs – and were used by about 5.3 million beneficiaries. The administration touted savings of $12 billion in net-covered-prescription drug costs, or approximately 44 percent lower aggregate net spending, if the MFPs had been in effect for 2024. For 2027, the administration estimated that people enrolled in Medicare prescription drug coverage would save $685 million in out-of-pocket costs under the MFPs. While seemingly impressive, these aggregated, theoretical savings based on retrospective data continue to tell only one aspect of the entire Medicare landscape.

CMS IPAY 2027 Announcement

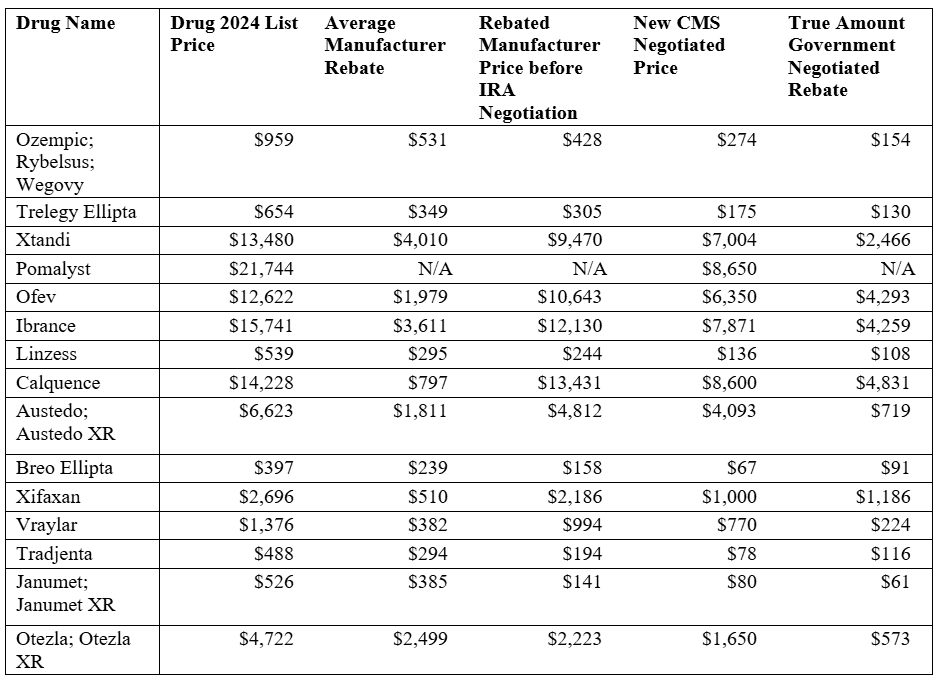

Under the Medicare Drug Price Negotiation Program, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) directly negotiates prices for high-expenditure, single-source Part D drugs lacking generic or biosimilar competition. For IPAY 2027, CMS finalized MFPs for 15 selected Part D drugs after a year-long negotiation process with manufacturers. The table below, from the CMS fact sheet announcing the MFPs, demonstrates the range of projected savings.

Source: CMS IPAY 2027 Fact Sheet

Headline Savings and Comparison to IPAY 2026

CMS’ 2027 estimates show larger aggregate savings in both absolute and percentage terms: $12 billion in net savings (44-percent reduction) excluding the coverage gap discount program (CGDP), and about $8.5 billion (36 percent) when CGDP is incorporated. Under the CGDP – or the Manufacturers Discount Program as it is now called – participating manufacturers are required to provide discounts on applicable drugs in the initial and catastrophic-coverage phases of Part D. In other words, a wide-reaching discount program already resulting in beneficiary savings without the IRA MFPs. On the beneficiary side, CMS projects that, under the defined standard Part D benefit, enrollees could save an estimated $685 million in out-of-pocket costs in 2027 from these MFPs alone.

The IPAY 2027 figures are frequently contrasted with those from the first negotiation cycle, IPAY 2026, which involved 10 Part D drugs used for conditions such as diabetes, heart failure, autoimmune disease, and blood cancers. For the first round, CMS estimated that if the 2026 MFPs had applied in 2023, Medicare would have saved about $6 billion in net spending – roughly a 22 percent reduction – while beneficiaries were projected to save about $1.5 billion in out-of-pocket costs in 2026.

The second-year discounts are deeper on average than those in the first year, in part because the 2027 group includes very high-spend GLP-1s and oncology agents with substantial room between list prices and MFPs. Additionally, the absolute out-of-pocket gain to beneficiaries from MFPs alone is smaller than in 2026 because the broader Part D redesign (including the new out-of-pocket cap) is now doing much of the heavy lifting on catastrophic costs. The table below shows numerous calculations to demonstrate the “true” amount of the government-determined rebate. Note: Pomalyst did not have sufficient data to assess average manufacturer rebates, and thus comparable numbers could not reliably be generated. Based on the calculations, some rebates may be impactful; others are clearly not huge sources of savings for either the government or beneficiaries.

Source: CMS IPAY2027 fact sheet; J Manag Care Spec Pharm.; author’s calculations

Potential Implications for Beneficiaries

For individual Part D enrollees, the practical impact of these new MFPs will depend on benefit design, utilization, and interactions with other IRA changes.

- Interaction with the Part D out-of-pocket cap: As of 2025, Part D enrollees face a $2,000 annual cap on out-of-pocket drug spending (rising to $2,100 in 2026), after which they owe no additional cost sharing for covered Part D drugs. For heavy users of high-cost products such as GLP-1s or oral oncology drugs, this cap may already substantially limit spending; the MFPs then reduce the amount of cost sharing they incur before hitting the cap and may mean fewer people hit the cap in the first place.

- Coinsurance versus copay designs: Beneficiaries in plans that charge coinsurance (a percentage of the drug’s price) should see a direct reduction in per-fill costs when the MFPs take effect, assuming the MFP is below the plan’s current net price. Those facing flat copays may see little or no immediate change if the plan keeps the same copay amount, even though the plan’s own liability falls. The magnitude of out-of-pocket savings from negotiation is inherently uncertain and will vary by plan design and beneficiary utilization.

- Formulary coverage and access: A key structural component is that Part D plans are required to cover all selected drugs with MFPs, including all dosage forms and strengths, which may reduce the risk that a beneficiary finds a high-profile drug excluded from their plan or subject to unusually restrictive utilization management compared to non-selected competitors. CMS has indicated it will scrutinize tiering and management practices that could undermine access to selected drugs.

- Distribution of gains: Because the IPAY 2027 list includes several specialty and high-cost products, savings will be concentrated among beneficiaries who use these specific drugs rather than spread evenly across all Part D enrollees. At the same time, program-level savings can exert downward pressure on premiums and on federal Part D spending over time, potentially benefiting a broader population indirectly.

Points of Confusion and Contention

Aggressive “negotiations” to address beneficiary needs

Outside of the IRA negotiations, the White House had long been signaling that drug pricing would be handled aggressively, with a mix of Most-Favored-Nation (MFN) rhetoric and tariff brinkmanship. The message to manufacturers and foreign governments has been: Accept lower prices, or face some combination of trade penalties, import restrictions, or regulatory pressure. That’s not a traditional negotiation over value; it’s a leverage campaign.

The IRA’s negotiation authority is just the domestic counterpart to these external tactics. MFN talk toward other countries says, “we’ll make you pay if you don’t give us your lowest price.” The IRA framework says to manufacturers, “we’ll tax you out of the Medicare market if you don’t sign the MFP contract.” This approach doesn’t build a principled, predictable pricing framework; it levies the threat of punishment to drag prices down in discrete skirmishes.

As noted in POLITICO, Chris Klomp, the Director of Medicare, stated this clearly:

The key factor in the second round of price negotiations was the administration’s willingness to walk away from the table if they didn’t reach a deal, said Chris Klomp, deputy administrator of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, which handled the talks.

“A true negotiation implies that you might not reach a negotiated outcome,” Klomp said.

Thus, framing the IPAY 2026 and IPAY 2027 rounds as “negotiations” obscures what’s really going on. The same strategy that underlies MFN posturing and pharmaceutical tariff threats – naming and shaming manufacturers and threatening punitive penalties for headline-ready percentage cuts – has simply been imported into Medicare. The millions of beneficiaries that CMS is arguably responsible for representing have no say in the determination of an acceptable price, so the central decision-making process can’t be called a negotiation. It creates a blurred line between legitimate purchasing strategy and ad hoc economic coercion, and it makes it hard to argue that the resulting prices are the product of a thoughtful, evidence-based process rather than the latest move in a high-stakes game of chicken.

Any “value” created is narrow

On paper, the IPAY 2027 MFPs deliver several billion dollars a year in lower Medicare spending on a carefully curated list of high-spend drugs. But those “savings” are calculated relative to a baseline that assumes the old system – escalating list prices and opaque rebates – would have continued unchanged. There is still no serious accounting for how manufacturers will respond when a significant share of their Medicare revenue is capped by statute: higher prices in commercial markets, trimmed investment in follow-on indications, different launch strategies, or more aggressive contracting outside Medicare. Those downstream effects are invisible in the headline savings figure, but they are very real economic costs.

For beneficiaries, the purported benefits are muddled. The projected out-of-pocket savings sound impressive in aggregate, but they are narrowly concentrated among people taking a small set of drugs and sit on top of a redesigned Part D that would have reduced catastrophic exposure anyway. A sizable share of the “benefit” claimed through MFPs is arguably just double-counting: The out-of-pocket cap and restructured liability phases are doing most of the heavy lifting, while MFPs marginally lower the prices that feed into that benefit formula.

The graph below shows that the comparative impact of these “negotiations” is less than the market itself could drive. Only four of the 15 selected drugs (the graph omits Pomalyst due to sparse data) have an IRA rebate that outperforms the market. This is more than last year’s MFPs – which had no IRA rebates that out-performed the market – but it is not a ringing endorsement of the program’s success.

The Ever-present Mismatch of GLP-1 policy

As if the GLP-1 coverage decision-making process wasn’t convoluted enough, the gap between the semaglutide MFP for IPAY 2027 and the earlier, highly publicized GLP-1 “deal” is a useful case study in how ad hoc this policy environment has become. The administration has announced two different prices for the same medication that is intended to be administered in the same program. We now have two competing reference points:

- a statutory MFP for semaglutide inside Part D, produced by the IRA’s statutory process and meant to apply across plans; and

- a program-specific GLP-1 price, marketed as a breakthrough “deal,” that in some cases lands below, and in other cases above, the semaglutide MFP – depending on channel, indication, and details of the arrangement.

CMS has already announced that the separately negotiated GLP-1 deal will supersede the IRA MFP outcomes, which could support a narrative that the Medicare drug negotiation program is not a rational, rules-based anchor for the market, but instead is a stopgap for the price-setting endeavors being led by the White House. It tells patients and plans that there is no single “true” price for these drugs; there are multiple, politically negotiated prices depending on where you sit. The result looks less like a principled, evidence-based pricing regime and more like a layered set of one-off bargains.

Conclusion

CMS’ long-awaited announcement of maximum fair prices for covered drugs in the Medicare Drug Negotiation Program closes one of the largest outstanding items on its 2025 regulatory agenda. The accompanying data, however, do not provide clear evidence of the benefits of the IRA Medicare drug negotiation program. While the savings seem significant, further analysis of the announcement identifies calculated inefficiencies, an overrepresentation of benefit, and the continued lack of hard evidence that any savings will truly materialize in Part D. The health care industry still has not experienced a world in which any MFP has been effectuated for Part D, and until this is the case, the impact of any MFPs remains theoretical and unsubstantiated.