Insight

April 27, 2022

Legislative Options for Regulatory Reform

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

- A surge in costly regulatory activity under the Biden Administration is likely to spur renewed interest in legislative proposals to reform the rulemaking process with the aim of reducing regulatory burdens.

- Specifically, the continued emergence of costly regulatory policies from the executive branch is likely to increase pressure on Congress to constrain agencies’ rulemaking ability.

- While reform is unlikely in the near term, past congressional proposals could provide models for future reform; possible legislation could approach reform by updating the regulatory process to improve future rules, removing existing outdated and unnecessary regulations, and reasserting Congress’s authority over rulemaking.

INTRODUCTION

The Biden Administration entered office promising to use the regulatory capacity of the federal government to enact its agenda should Congress fail to do so. And, as Congress has failed to pass much of the administration’s agenda, the administration is keeping that promise, publishing final rules with an estimated total cost of more than $200 billion in its first year alone. The regulatory pace shows no sign of slowing in year two, as the administration has announced plans for rules aimed at climate change, labor, and competition issues – to name just a few areas of focus.

Following the comparative lull during the four years of the Trump Administration, the recent surge in costly regulatory activity and its likely continuation, coupled with public pressure to limit regulation that contributes to inflation, could prompt lawmakers to reform how rules are made with the goal of reducing regulatory burdens.

This analysis reviews some of the likeliest reforms that may be considered in 2022 and beyond and considers their strengths and weaknesses.

REGULATORY PROCESS REFORMS

The rulemaking process is a good place to start when considering how to reduce burdensome regulation. That process was created by the Administrative Procedure Act (APA), a 1946 law that established such rulemaking tenets as publication of proposed and final rules in the Federal Register and public notice-and-comment requirements. The process as enacted remains largely the same. In the 76 years since, Congress has established dozens of agencies unimagined when the APA was passed, including the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), and the Department of Health and Human Services. Its authors likely did not envision a future with single rules costing billions of dollars, making the APA ripe for modernization.

Administrative Procedure Act Overhaul

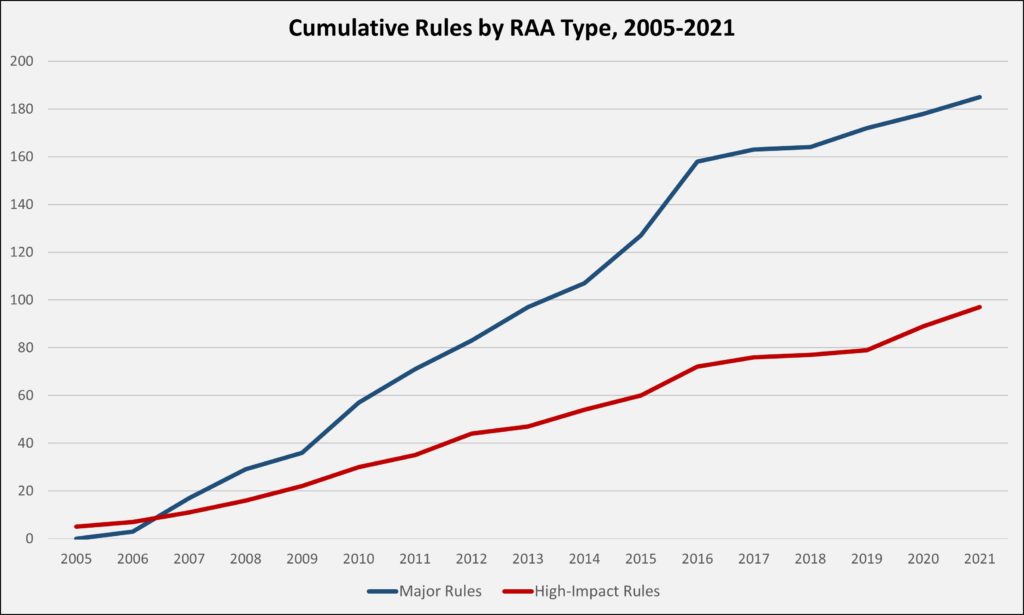

One option for lawmakers to consider is a major overhaul of the APA. Over the last decade, the Regulatory Accountability Act (RAA) has represented the most comprehensive and serious effort, passing the House of Representatives in multiple Congresses. The RAA would revise the definition of a “major” rule and create a new tier of rule called “high-impact.” Major rules would be defined primarily as those with an annual economic impact of $100 million, and high-impact rules as those exceeding $500 million (with those thresholds updated for inflation every five years). The chart below shows the cumulative number of final rules published under each of those thresholds since 2005, using information from the Regulation Rodeo database (none have been published so far in 2022).

Both types of rules would receive additional scrutiny prior to promulgation, including increased standards for the assessment of costs and benefits and a requirement for the consideration of viable alternatives made available for public comment. In addition, an agency must adopt the alternative that maximizes net benefits unless given approval for another alternative by the administrator of the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs.

High-impact rules would be subject to a further layer of scrutiny. Once such a rule is proposed, anyone can petition the agency to hold a public hearing to hash out factual disputes over the agency’s justification for the rule. The hearing would include testimony and cross-examination, resulting in an official decision either upholding the agency’s original factual basis for a rule or requiring some change.

Other major components of the RAA include allowing new administrations to recall midnight rules (those issued in the last 60 days of an outgoing administration) submitted to – but not yet published by – the Federal Register, requiring interim final rules to be finalized, modified, or rescinded within 180 days, and extending benefit-cost analysis to guidance with an economic impact of $100 million or more annually.

Among the strengths of this type of approach are its comprehensiveness and its delineation of rules at various levels of economic impact. Rules that will have a major or high-impact economic effect are deserving of extra scrutiny before they are proposed and finalized to ensure that their outsized impacts can be justified. The most glaring weakness for this type of approach is political, as opponents often claim that it would make it more difficult for agencies to issue needed regulations. This argument falls flat, however, because the most “needed” regulations would, if truly necessary, be the easiest to justify even when facing additional scrutiny.

Regulatory Flexibility Act Reform

Another option is to reform the regulatory process on a smaller scale. The Regulatory Flexibility Act (RFA) is a four-decade-old law designed to ensure that agencies consider the impacts of their rules on small entities – primarily small businesses – that are disproportionately affected by regulatory burdens. One key component of the RFA is its Small Business Advocacy Review (SBAR) panels, which occur when a potential rule is determined to have a “significant economic impact on a substantial number of small entities.” As the name implies, these panels convene small entities prior to proposal of a rule for feedback on how the rule could affect small businesses. At present, however, they are only required of EPA, OSHA, and the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau.

Like the RAA, the Small Business Regulatory Flexibility Improvements Act (SBRFIA) is a well-trodden reform idea that previously cleared the House of Representatives multiple times. One of its main reforms would be to expand the SBAR panel process to all agencies. It would also empower the chief counsel of the Small Business Administration’s (SBA) Office of Advocacy with the ability to write regulations on how federal agencies comply with the RFA. This authority is designed to address one of the RFA’s major problems, which is that it can often be ignored by agencies with little consequence. SBRFIA would also require agencies to consider both direct and indirect costs and benefits to small businesses.

The strength of this type of RFA reform is that it would substantially improve a policy that has produced results in reducing unnecessary regulatory costs. Despite the RFA’s loopholes, the SBA Office of Advocacy found that in fiscal year 2021 alone the law helped save $3.2 billion in costs on small entities, and billions more in previous years. Increasing the RFA’s effectiveness would likely add to that tally.

Its weakness is that it only pertains to a relatively small subset of rules as compared to the RAA – although it does cover many that have hefty price tags.

REGULATION REMOVAL

Another possible avenue for reducing regulatory burdens is to identify and remove existing regulations. Presidential administrations going back decades have tried to require some form of review process for existing regulations. Often, however, these efforts have yielded unimpressive results. One likely reason for this is that these measures have typically asked agencies to go over their own regulations and identify those that are unnecessary or redundant. Agency personnel often place increased importance on issues in which they have expertise, so they are reluctant to put forth meaningful recommendations. Some in Congress have considered trying to improve the process by 1) providing a meaningful statutory requirement, as opposed to an executive directive, and 2) removing agencies from making key decisions on which rules should go.

Independent Review Commissions

The reform that has gained the most traction is the establishment of an independent commission to come up with candidate regulations to be repealed. The Searching for and Cutting Regulations that are Unnecessarily Burdensome (SCRUB) Act is one such version of this idea. The crux of the SCRUB Act is to establish a Retrospective Regulatory Review Commission, made up of outside experts, that would develop a list of regulations to repeal, and that list would then be sent to Congress for an up-or-down vote. The idea was predicated on the Base Realignment and Closure (BRAC) commissions used to determine which military bases to shutter following the Cold War. The BRAC model helped members of Congress avoid political consequences for closing individual bases by cloaking those closures in a broad measure drafted by outside experts seeking greater Department of Defense efficiency. The same idea applies to the SCRUB Act: By having members of Congress vote for or against a package of repeals developed by regulatory experts, the bill seeks to minimize the political ramifications of voting to repeal individual regulations.

The strength of this idea is that it is a clear improvement over the ad hoc efforts of presidential administrations. Independent experts – from across the political spectrum – would be far better able to fairly judge whether a regulation is necessary than an agency official implementing said regulation. A weakness is that the repealed rules may not yield much in the way of burden reductions. Often, a regulated entity has already spent resources to comply with these existing regulations, and the costs of compliance tend to be greatest on the front end rather than years after the regulation has been in place.

Removing Regulations Paused During the COVID-19 Pandemic

Another idea is to focus solely on those rules suspended or modified by agencies during the COVID-19 pandemic. Although different in structure to the SCRUB Act, the Coronavirus Regulatory Repeal Act (CRRA), first introduced in 2020, considered such an approach. Rather than create one commission for the government, it would create several commissions, one for each committee of jurisdiction in the House and Senate. These commissions would consist of committee members and the head of each agency under its jurisdiction.

Instead of developing a list of rules to repeal or modify permanently, the commissions would develop a list of rules to keep. Those rules not on the list would be permanently repealed or modified (commensurate with the action taken during the COVID-19 emergency). Those rules on the list would have to be approved by the House and Senate and signed by the president to remain in place. If not, the rules would be repealed.

The strength of targeting repeals on regulations paused or altered during the pandemic – like those previously barring certain uses of telehealth, for example – is that there is clear evidence they can be repealed or modified with minimal, if any, effect on public health and safety. One weakness is that it would only affect relatively few regulations across the entire body of federal rules. A second, specific to the CRRA, is that its many commissions are structurally unwieldy and would be more difficult to implement than something like the SCRUB Act’s approach.

CONGRESSIONAL INVOLVEMENT

A third category of reform stems from the idea that a primary reason for the continued rise in regulatory costs is that Congress has delegated a great deal of authority to executive branch agencies. While most of this delegation may be necessary – one winces at the thought of Congress trying to enact specific emissions limits, for example – some have suggested that Congress should reassert its authority over rulemaking.

Congressional Approval of Rules

One idea for reasserting Congress in the regulatory process is to have it approve of certain rules before they are allowed to go into effect. The most well-known of these ideas is the Regulations from the Executive in Need of Scrutiny (REINS) Act. Simple in its design, the REINS Act would require major rules – as determined by the Government Accountability Office – to be approved by Congress before they could take effect. The idea is that major rules have such outsized economic impact that Congress should have to approve them to ensure agencies appropriately applied their delegated authority. Based on the last 20 years of rulemaking data, the affirmative approval requirement would have applied to about 2.2 percent of all final rules issued (for those rules determined to be major on a cost basis).

The strengths of the REINS Act are its simplicity and its limitation of applying to a small fraction of federal rules. One weakness is what it would require of Congress. It is easy to see how the body’s partisan nature would be exacerbated by trying to pass approval resolutions. The REINS Act would also require Congress to spend significant amounts of time trying to affirm what agencies have done, which would reduce its legislative capability even further. A second weakness is that it would inevitably lead to a large waste of agency time and resources spent on rulemaking that is ultimately rejected for political purposes.

Regulatory Budget

While the REINS Act would reassert Congress’ authority at the end of the rulemaking process, another approach would have Congress set limits on the front end. Congress could do so through a regulatory budget, which would set a cap on the total net economic cost of an agency’s rules. A form of the regulatory budget was implemented through the executive branch during the Trump Administration. That effort helped reduce the average annual total cost of final rules from $110 billion during the Obama Administration to $10 billion during the Trump Administration.

A congressionally enacted budget could be a significant improvement, as it would encompass the entire federal bureaucracy, whereas the Trump budget excluded independent agencies. It could also take many forms. A version introduced in 2014 would put Congress in charge of setting the budget and create an independent Office of Regulatory Analysis to determine regulatory costs – rather than relying solely on agency estimates. A legislative version of the Trump Administration’s process has also been considered, although it would have the administration set the caps and provide the estimates.

A strength of a regulatory budget is that it allows Congress to set parameters for regulatory costs without having to debate the merits and soundness of individual rulemakings, as it would have to do with a REINS Act-like approach. A weakness is that, like with any requirement pertaining to regulatory costs, estimates of economic impact could be manipulated – and there are certain costs and benefits that are simply not quantifiable.

CONCLUSION

The increase in regulatory costs from the Biden Administration is likely to produce renewed calls for regulatory reform, particularly if the pace of costly regulations continues and high inflation persists. While reform is unlikely in the near term, past congressional proposals could provide models for future reform; possible legislation could approach reform by updating the regulatory process to improve future rules, removing existing outdated and unnecessary regulations, and reasserting Congress’s authority over rulemaking.