Insight

February 22, 2022

Rating the Credit Rating Agencies Over the Pandemic

Executive Summary

- The financial stresses of the global financial crisis of 2007-2008 and the COVID-19 recession have provided significant real-world stress tests of the performance of the credit rating agencies.

- Comparing financial and public health crises, however, reveals how very different the circumstances are for governments, the economy, and the credit rating agencies, themselves.

- Over the course of the pandemic, the credit rating agencies have added a valuable stabilizing force to markets, provided price-sensitive information to investors in a timely fashion, and accurately predicted which companies were most at risk of failure.

Introduction

Credit rating agencies perform a vital function in the modern economy by assessing the likelihood of default of debt instruments and the issuers of debt instruments, including companies and sovereign nations. The necessity of some form of credit scoring has not, however, made credit rating agencies immune from criticism, and the industry has endured scrutiny from Congress for decades. Much of this criticism stems from the key role played by credit scores in the global financial crisis of 2007-2008; the highly complex toxic mortgages that eventually were downgraded to “junk” status, causing losses of half a trillion dollars, were inappropriately rated as safe investments by the “Big Three” credit rating agencies – Moody’s, Standard & Poor’s, and Fitch Ratings. Key critiques of credit rating agencies in times of crisis typically revolve around inappropriate asset valuation, response time, and inconsistent and opaque methodology.

The unique economic challenges posed by the COVID-19 pandemic and subsequent recession therefore represent the most significant challenge and opportunity for credit rating agencies. The context, of course, is not identical. The global financial crisis and the COVID-19 recession have had different economic implications over different timelines, and the credit rating agencies themselves have seen subsequent legislative reform and invested billions into their management and risk processes. Yet the performance of the credit rating agencies remains as important as ever, with access to federal emergency lending facilities tied directly to an applicant’s credit rating.

Understanding these differences and the continued vital role of the credit rating agencies, how should one rate the performance of the credit rating agencies over the course of the COVID-19 pandemic?

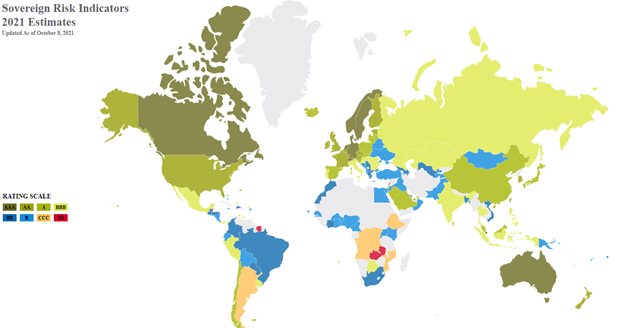

The Credit Rating Agencies and Sovereign Credit Ratings

Credit rating agencies issue credit ratings, not just for individual companies, but also for countries in what are known as sovereign credit ratings. Governments raise capital by issuing government bonds and selling them to private investors, and a sovereign credit rating represents the assessment of a credit rating agency of the likelihood that a country will be able or willing to meet its future debt obligations. Sovereign credit ratings represent the best indicator of sovereign default risk, despite the criticism the credit rating agencies have received for a perceived failure to react fast enough to crises, including the European debt crisis and subsequent Greek debt default.

Source: S&P Global

A perceived lack of timeliness is the key criticism of the credit rating agencies in a pivotal University of Cambridge paper assessing sovereign credit ratings during the COVID-19 pandemic. That paper found that between January 2020 and March 2021, the Big Three credit rating agencies issued 99 sovereign rating downgrades on 48 countries. Of these, the paper draws a comparison between S&P Global’s sovereign rating downgrades in the six months beginning in February 2020 (19) and six months after the collapse of Lehman Brothers in September 2008 (31). The paper’s authors use this comparison of governments in wildly different stages of economic health, against entirely different global economic contexts, and in response to different economic crises to suggest that, by having downgraded fewer sovereign governments, the credit rating agencies were “coasting in a business-as-usual mode.”

While the pandemic represented a sudden and unanticipated economic shock, it is not immediately obvious that the credit rating agencies should have operated any differently from business-as-usual or deviated from their schedule of sovereign reviews as required by regulation. In addition to providing investors with the highest degree of investment comfort commercially available, credit rating agencies perform a valuable stabilizing role on markets. Scheduling out-of-season review, as the Cambridge paper suggests, may instead have exacerbated the negative financial impacts of the pandemic, and in particular, any perceived financial instability, including the 2020 stock market crash.

That the credit rating agencies operated per their usual procedures at an unusual time indicates that the flexibility built into their process as a result of industry and regulatory reform post Dodd-Frank may be working. The Cambridge paper also noted that, despite its criticisms of the industry, sovereign rating news from Moody’s and S&P Global conveyed price-relevant information to the bond markets, the most valuable information available to investors.

The Credit Rating Agencies and Companies

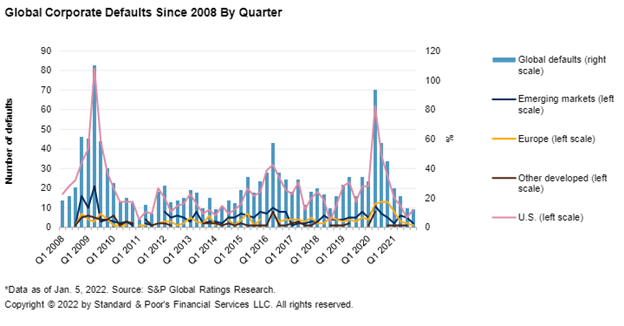

Companies, fortunately, collapse far more readily than governments; it was expected that the COVID-19 recession would trigger a rise in the global level of corporate default.

Source: S&P Global

While increased financial distress in the form of corporate default was anticipated once the economic shock of the COVID-19 recession was identified, the corporate default rate is considerably lower than that experienced as a result of the global financial crisis, and not much higher than the rate in 2015.

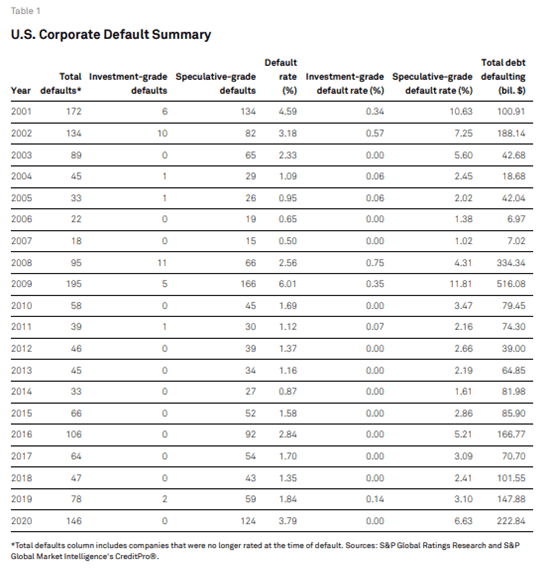

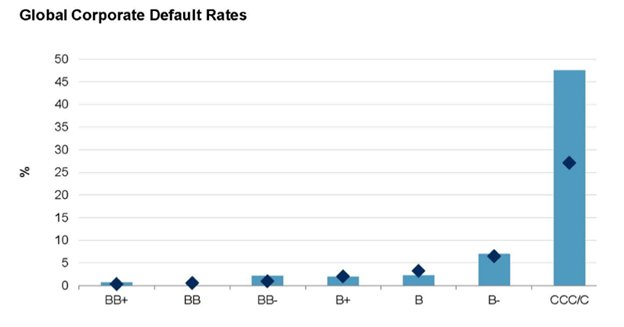

If credit ratings are to be relied upon, corporate default should be concentrated on lower-rated financial instruments. While the credit rating agencies differ in their credit rating methodologies and the credit rating scores that they give, ratings can be broadly summarized across the Big Three as “investment grade” (the term used to imply a low risk of default, and an umbrella term for the highest ratings offered by the credit rating agencies) or “speculative grade” (a higher risk of default, and the lowest ratings offered by the credit rating agencies).

Source: S&P Global

In 2020, 96 percent of all corporate defaults were of speculative grade. While investment grade tracked close to their historic default average, speculative grade bonds defaulted at a level far above historic projection.

Source: S&P Global

That default was concentrated in those issuers that S&P Global indicated were most likely to default indicates that the credit rating agencies are performing their role as quantifiers of creditworthiness and providing the best information possible to investors. Although much has been made of the differing rating approaches by the Big Three what is more important than the inherent factual basis or methodology of any individual rating is the ability to compare ratings to other potential investments. A Fitch rating, for example, has less or no value in isolation than it does as compared with all other Fitch ratings that are compiled using the same methodology. It is indicative of the success of that methodology that the vast majority of corporate defaults noted by S&P were of the lowest rating given by S&P.

Also of note, 2020 saw the default of zero companies rated investment grade (the remaining 15 percent of defaults were of unrated entities). 2008 saw the default of 11 companies rated investment grade; this seems to suggest that credit rating methodologies are only improving and that comparisons between the economic circumstances of the global financial crisis and the COVID-19 recession that fail to take these differences into account will fail. One of these key differences, of course, is the billions of dollars of support for companies issued under the Federal Reserve emergency lending facilities and other sources of pandemic stimulus. While there is little to indicate that credit rating agencies are not presenting an accurate picture as to the health of the overall economy, that health is itself somewhat artificial given the nature of economic support provided by the Fed.

Conclusion

The global financial crisis represented a failure of instrument and issuer. The inappropriate valuation of highly complex securitized mortgages triggered in turn the collapse of investment grade issuers. Neither of those sources of global systemic economic stress are apparent in the COVID-19 recession and aftermath. It remains to be seen whether the credit rating agencies could cope with a similar set of circumstances, although regulation and better risk management at the credit rating agencies themselves would suggest that they are considerably better equipped to do so. In these quite different circumstances, however, the credit rating agencies have stabilized markets, provided timely price-sensitive information to investors, and have accurately predicted which instruments and issuers would most likely fail.