Insight

October 24, 2018

The Community Reinvestment Act: A Primer

Executive Summary

- Congress passed the Community Reinvestment Act in 1977 to prevent banks from withholding loans or general banking services from individuals living in low-income communities.

- The CRA encourages “banks to open new branches, provide expanded services, and make a variety of community development loans and investments” in these low- and moderate-income communities, with a focus on physical presence and investment in these areas.

- While the banking industry has changed since the CRA became law, the CRA itself has not; it now imposes anachronistic requirements on banks, prompting regulators to propose changes to the CRA.

Introduction

The Community Reinvestment Act (CRA) has received outsized attention recently. Bank regulators and community activists have clashed over proposed modernization to the CRA, as a recent Wall Street Journal article reported. Supporters and opponents of the modernization have lobbed op-eds back and forth, and most recently Senator Elizabeth Warren sparred with Office of the Comptroller of the Currency Chairman Joseph Otting over proposed updates in a Senate hearing.

As debate over the CRA and its future heats up, it’s important to begin by understanding the history of the CRA, how it works today, and what reform may look like.

The History of the CRA

Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal created the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) in 1934 to insure mortgages and help provide liquidity in the housing market. While the FHA made home ownership possible for many, some banks refused to originate mortgages to low-income communities and in some instances even denied banking services such as checking or savings accounts to these communities. Collectively, these practices became known as redlining.

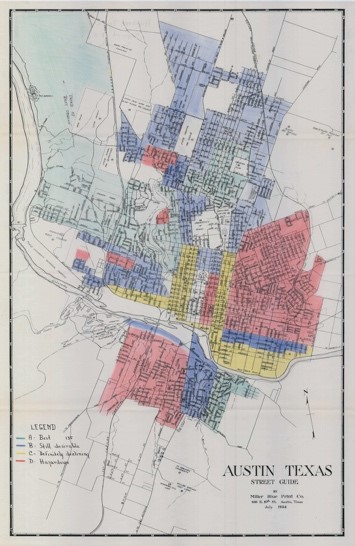

Redlining in Austin, Texas in 1934.

In 1964 Congress passed the Civil Rights Act, statutorily declaring “no person in the United States shall, on the ground of race, color, or national origin, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefit of, or be subjected to discrimination under any program or activity receiving federal financial assistance.”

While this made government financial discrimination illegal, the Civil Rights Act failed to include language that would prohibit private financial discrimination. Lawmakers corrected this oversight over 10 years later with passage of the CRA in 1977, essentially banning redlining and requiring banks “to help meet the credit needs of the local communities in which they are chartered.”

How the CRA Works

Three financial regulators oversee implementation and enforce compliance with the CRA: the Federal Reserve (Fed), Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), and Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC). CRA compliance applies to all FDIC-insured depository institutions, including national-bank holding companies, saving associations, and state-chartered banks.

When evaluating banks for CRA compliance, regulators conduct three tests: a) a lending test that evaluates the bank’s home mortgage, small business, farm, and community development lending; b) an investments test that evaluates a bank’s record of helping to meet the credit needs of its assessment area through qualified community development investments and grants that benefit the area; and c) a services test that evaluates the availability and effectiveness of a bank’s systems for delivering retail banking services and the extent and innovativeness of its community development services. Regulators consider other activities under the CRA, too. These are collectively known as community development, and can include offerings of social services, youth programs, homeless centers, soup kitchens, health care faculties, drug rehab centers, and even lead paint abatement.

The CRA’s multi-part evaluation process first appraises banks by size and sorts them into three classifications: small banks with assets less than $290 million, intermediate small banks with asset between $290 million and $1.16 billion, and large banks exceeding $1.16 billion. Small banks are only rated for their lending performance, and intermediate small banks and large banks are evaluated considering all three factors.

Based on their performance on the tests, banks are rated as either: Outstanding, Satisfactory, Needs to Improve, or Substantial Noncompliance. At the end of each evaluation, agencies prepare a written performance report on the bank’s activities, which is then made available to the public.

CRA ratings factor into regulators’ decisions to approve or deny bank mergers, acquisitions, branch expansions, and branch consolidations. Put another way, banks need to have a good CRA rating to pursue changes in their business. Thus, penalties under the CRA include denial of mergers or branch expansions, as well as the loss of expedited processing on corporate and regulatory affairs.

Banks are further incentivized to adhere strictly to CRA provisions as the penalties for bad banking practices that warrant a CRA rating downgrade get worse the further a bank is downgraded. For example, a downgrade from “Outstanding” to “Satisfactory” is much more manageable than a downgrade from “Satisfactory” to “Needs to Improve.”

The CRA Today

In assessing the CRA, it is useful to look at how it is achieving its goals, and whether it is functioning the way it is supposed to today. The CRA outlawed redlining, ending that particular practice, but it is less clear whether the law actually expanded access to credit and banking services in low-income neighborhoods. A Competitive Enterprise Institute study notes that “the Community Reinvestment Act does not appear to have had any positive effect on lending to residents of [low- and middle-income] neighborhoods. In fact, it appears to have had a negative effect on CRA lenders and [low- and middle-income] residents alike.”

While the CRA likely did not increase access to credit, it is almost certainly not functioning today the way it should. The law is over 40 years old, and while the banking industry has modernized significantly since 1977, the language in the CRA has not undergone any similar modernization. The Manhattan Institute notes that “notwithstanding this changed landscape, traditional banks must cope with the 1977 law as if the world is little changed; they are judged, for instance, on the extent to which they serve ‘LMI’ (low and moderate-income) neighborhoods in their ‘assessment area.’”

The application of physical “assessment areas” in bank ratings is the primary outdated part of the law. Under current implementation, evaluations for CRA compliance rely on servicers having physical brick-and-mortar locations as their nexus. More specifically, an assessment area is considered to be the “geographies where the bank has its main office, branches, ATMs and surrounding geographies in which the bank has originated or purchased a majority of its loans.” Under this definition, the evaluation excludes lending that occurs online, which leaves out banks that conduct lending practices partially or totally online via the Internet. For example, take the case of Ally, the only fully online bank in the United States (and which was noted in a previous American Action Forum Insight on the CRA): Ally is headquartered in Detroit, yet it receives no credit for fair lending there as it operates only online.

Recall that regulators use CRA ratings when deciding whether to approve bank business decisions around expansion, consolidation, mergers, or acquisitions. Because online-only banks cannot comply with the CRA, regulators have no ratings for these banks, and therefore the banks cannot receive approval for such decisions. The same problem exists for banks that invest heavily in online banking. By not recognizing their work on modern platforms, the CRA prevents banks from changing as the market demands.

Further, by requiring a physical presence and therefore driving up the cost of providing banking services and credit to low-income neighborhoods, the CRA harms these communities by making it less likely that banks provide them banking services in more efficient ways. Given this focus on physical locations, banks have little incentive to continue to offer online loans to low-income communities since they are not factored into their CRA ratings, removing much of the CRA incentive system that is meant to make low-income lending appealing to banks.

Because the law has not changed how it evaluates banks, even though banks are changing how they operate by applying technology, the law imposes archaic requirements on banks, hurting both the industry and low-income communities.

The Future of the CRA

Cognizant of these and other problems with the CRA, the OCC sent out an Advance Notice of Proposed Rulemaking (ANPR) soliciting comments from the public regarding how regulators should modernize the regulatory framework surrounding the CRA. For any modernization to occur, however, other regulators must act: Fed Vice Chairman of Supervision Randal Quarles and FDIC Chairwoman Jelena McWilliams must issue either their own rulemaking or a joint-rulemaking, neither of which formally has been done.

While it’s hard to predict how these CRA updates will materialize, or if they do at all, the OCC’s ANPR paid special attention to the concerns about assessment areas outlined above. Under a new regulatory framework, online loans and digital offerings may be factored into a bank’s CRA servicing of their assessment area or perhaps factored into the community development considerations.

Conclusion

No matter its historical context and good intentions, a law only ought to exist if it is effective in practice. Yet, research shows the CRA has done little good. The CRA should be updated to better account for innovations in banking, allowing banks to take advantage of the efficiencies that technology affords while still promoting access to banking services in the places that need them.