Insight

October 27, 2025

The Dangers of Price-Setting Endeavors

Executive Summary

- While most pharmaceutical pricing debates have been focused on most-favored-nation price-setting and direct-to-consumer pharmaceutical purchasing channels, the larger and more significant issue of Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) Medicare price-setting has been unfolding in the background.

- The IRA drug negotiations are only one piece of the price-setting puzzle, and the president’s recent remarks on the issue showcased the danger of government-driven, politically based drug-pricing decisions.

- Price-setting, a blunt tool to meet political ends, cannot match market incentives for price reductions and sets a dangerous precedent for using taxes to implement economy-wide price-fixing, hampering innovation incentives for drugs and biologics.

Introduction

While most pharmaceutical pricing debates have been focused on most-favored-nation (MFN) price-setting and direct-to-consumer pharmaceutical purchasing channels, the larger and more significant issue of Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) Medicare price-setting has been unfolding. These so-called “negotiations” are so complex and opaque that even the government officials ostensibly driving the efforts seem to misunderstand – or choose to ignore for political purposes – the status of the federal government’s price-setting scheme.

Take, for example, President Trump’s comments in a recent wide-ranging health policy press conference. When waxing about the price of GLP-1s in the United States compared to those abroad, the president mused, “In London, you’d buy a certain drug for $130…and in New York, you pay $1,300 for the same thing. So now we’re going to be paying, instead of $1,300, you’ll be paying about $150.”

The president has made no secret that GLP-1s are a major target of the administration’s pharmaceutical price-setting interests. But what appears to have been misunderstood or simply ignored is that a GLP-1 product is currently enmeshed in the secretive IRA Medicare Drug Negotiation Program. It was certainly recognized by Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) Administrator Mehmet Oz, who is nominally leading the ongoing IRA negotiations, jumped in to smooth over the president’s remarks. The attempted clarification only further muddied the interpretation of the state of play, because Dr. Oz failed to note that, at the time of the press conference, negotiations were already closed: CMS had made its last, best offer to the participating companies.

To inform this muddled discussion, this insight walks through the state of the IRA negotiations for initial price applicability year 2027 (IPAY 2027), and explains why the IRA’s price-setting scheme will not only fail at its intended aim, but set a dangerous precedent for using taxes to implement economy-wide price-fixing, and hamper innovation incentives for drugs and biologics.

Imminent Pricing Announcements

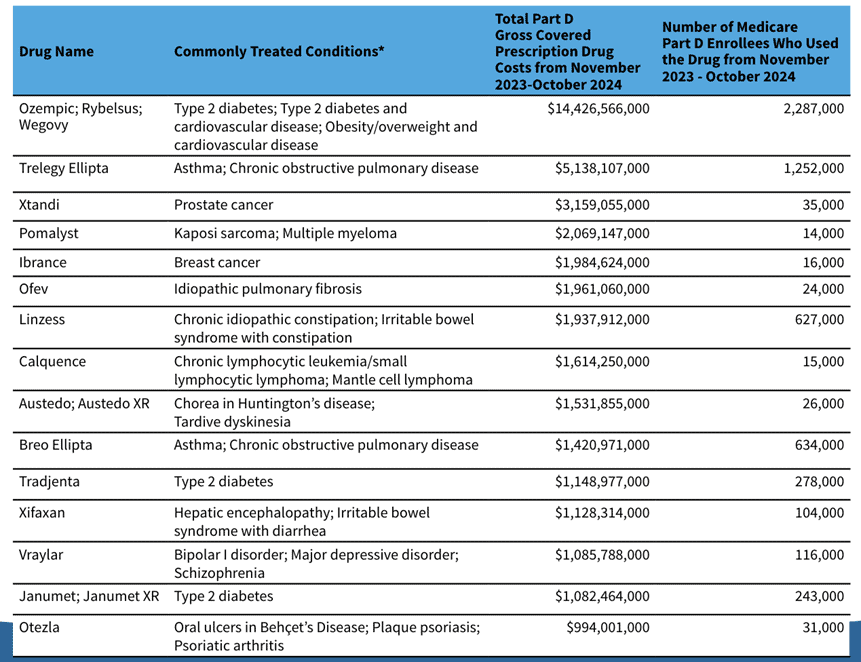

The IRA set forth very clear criteria for drug selection and strict timelines for CMS and industry to engage in “negotiations” to establish the maximum fair price (MFP) that Medicare will pay for the selected drugs. First, CMS selected 15 drugs (see table below) for IPAY 2027. These consist of high-spend or high-utilization drugs in Part D, with the aim of reducing spending in Medicare. The IPAY 2027 process, which has been underway since the beginning of 2025, unfolds over the course of the year. September 30, 2025, was the last day for negotiation meetings to take place, meaning all future deadlines are technically an exchange of paper. The fall deadlines are ultimatums:

- October 8, 2025: The last date by which CMS and participating drug companies may exchange additional written offers or counter offers.

- October 15, 2025: CMS’ deadline to send a final MFP offer to participating drug companies if the agreement was not reached during the negotiation meetings or the additional price-exchange process.

- October 31, 2025: The deadline for participating drug companies to accept or reject a final MFP offer from CMS.

- November 1, 2025: The IPAY 2027 negotiation period ends.

- November 30, 2025: Deadline for CMS to publish any agreed-upon MFPs through the second negotiation cycle.

Source: Medicare Drug Price Negotiation Program: Selected Drugs for Initial Price Applicability Year 2027

The declination of participation either means the removal of a drug from the Medicare or Medicaid formulary or, as American Action Forum President Doug Holtz-Eakin points out, “an increasingly large excise tax ultimately reaching 95 percent.” This results in a government-set price, which can hardly be called negotiation.

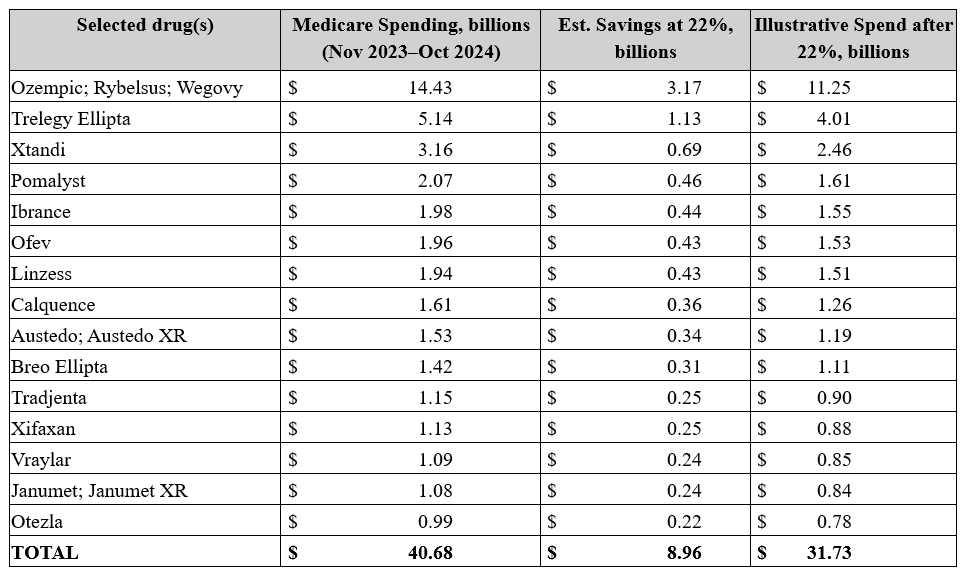

After the government effectively forces a company’s hand to accept the offered price, MFPs for this cohort will be effective starting in 2027. Given the approximately $41 billion spending base and the precedent of roughly 22 percent aggregate reductions from the first round, a reasonable planning assumption is mid-to-high single-digit billions in Medicare savings in 2027 from this cohort (heavily influenced by semaglutide and respiratory agents on the list) – hardly a Medicare-saving rate of return. The estimated savings can be seen in the table below.

Source: Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services and author calculations

Don’t mistake the estimated savings for immediate, market-wide list-price resets. IRA negotiation is narrower, slower, and more procedurally bounded than the president’s recent soundbites suggested.

The Fragility of the “Negotiation” Construct

Most recent pharmaceutical pricing discussions have focused on MFN pricing , disregarding swaths of the pharmaceutical development and manufacturing process with an unrealistic focus on a single list-price metric. The GLP-1 discussion, while often cited as an example of why price-setting models should be implemented in the United States, is complicated by the imminent inclusion of semaglutide in the previously enacted IRA price-setting model.

President Trump’s off-the-cuff GLP-1 pledge – claiming the monthly cost of Ozempic could drop to about $150 – illustrates how fragile the Medicare drug negotiation process is. CMS is behind closed doors finalizing MFPs, and the remarks instantly shaped expectations (and moved markets) before CMS’ IPAY 2027 negotiations are settled. As noted in the timeline above, the negotiation part of the process has concluded, and the parties (CMS and the drug companies) are only trading papers at this point. Most important, CMS has already made its last and final offer to the participating companies – in the case of the GLP-1 conversation, to Novo Nordisk – and the company is poised only to accept or reject that offer.

Agency guidance says it does not publicly discuss ongoing negotiations before releasing its formal explanation of any MFP, which further amplifies issues with the president’s comments. While it’s easy to dismiss the president’s statement as another throw-away remark, it raises the question of whether the $150 price tag may be more than a talking point and is an indication that there are instructions to outperform the Biden Administration’s first round of negotiations. These would represent the misaligned objectives with price-setting and negate the goal negotiation program was supposed to achieve. Regardless of the intent, research shows that the net prices announced from the first round of the Medicare drug negotiation program still exceeded those of foreign peers.

But CMS confidentiality requirements (which the president and Dr. Oz may have broken?) creates a one-way information valve where political rhetoric and company statements can create market confusion – see the market reaction to the president’s comment – without a mechanism to correct misimpressions in real time. Given the opacity of the process, remarks that imply a specific dollar amount risk being mistaken as fait accompli, even though MFPs apply only within Medicare Part D and are determined by the intense negotiations for specific company products.

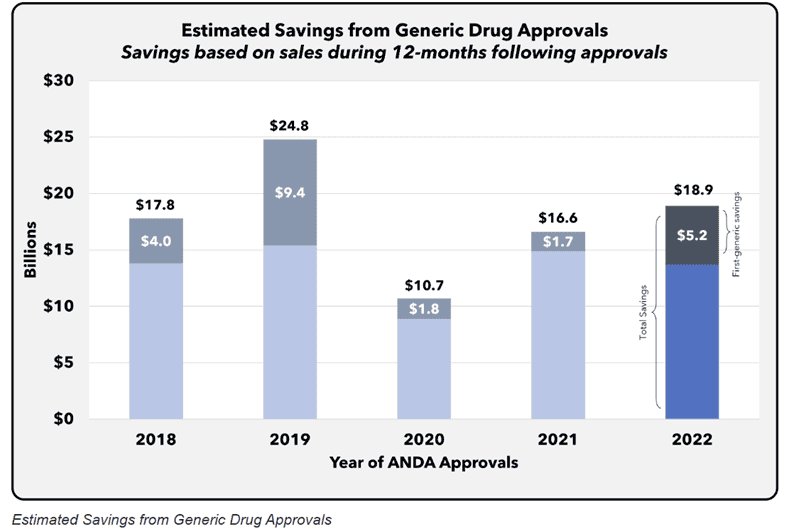

The Solution Is Not the IRA, But Competition

When policymakers talk about lowering drug spending, the cleanest, most durable way to do it is to let competition in, and the strongest proof comes from what happens when generics and biosimilars are introduced. FDA’s own economic work shows a simple relationship: As soon as even a few generic competitors enter the market, prices fall, and further entrants drive them lower still. In 2022 alone, the cohort of newly approved generics generated an estimated $18.9 billion in savings within 12 months. This is evidence that market entry of interchangeable products, not administratively set prices, delivers large recurring gains.

Source: Generic Competition and Drug Prices (FDA)

Generics dominate real-world use. Today, nine in 10 prescriptions filled in the United States are generic, reflecting both clinical substitutability and the powerful incentives that emerge once multiple manufacturers can compete on the same molecule. And the price gap is not marginal: FDA estimates generics are typically 80–85 percent cheaper than brand-name counterparts, a spread that compounds across chronic therapies and high-volume conditions. FDA’s “Generic Competition and Drug Prices” series documents this dynamic across markets.

Biosimilars bring the same logic to biologics, where single-source spending is concentrated. The Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) estimates that biosimilar competition lowered Medicare Part B spending on affected drugs by about 62 percent in 2023 versus a no-competition projection, with patients who used these products saving nearly $2,000 on average out-of-pocket that year. Independent oversight has reached similar conclusions. HHS’s Office of the Inspector General finds biosimilars have already reduced Part B costs for the program and beneficiaries while also highlighting headroom for still greater savings as uptake grows.

Crucially, none of this requires guessing the “right” price drug-by-drug. It requires timely entry of competitors and vigorous competition. That’s why avoiding the introduction of anticompetitive policies such as importing MFN pricing schemes from centralized health care systems or artificially creating exclusivity prices through CMS price setting that postpone first-generic or first-biosimilar launches is so important. Among all potential levers to tame drug spending, introducing generics and biosimilars is the most straightforward, effective, and proven method available. It scales automatically across molecules, preserves access, and aligns with how purchasers procure drugs. Policymakers who want lower drug prices should focus on everything that accelerates entry and substitution, because once competitors are in the market, the savings show up quickly and keep compounding year after year.

Conclusion

The IRA price-setting negotiations, among a host of similarly intended schemes, are so complex and opaque that even government leaders appear confused about their status. In sum, the government’s price-setting efforts will not only fail at their intended aim but set a dangerous precedent for implementing economy-wide price-fixing.