Research

March 8, 2021

Food Insecurity and Food Insufficiency: The Impact of COVID-19

Executive Summary

- Official reports and countless news stories suggest significant increases in the number of Americans going hungry during the COVID-19 pandemic despite substantial financial aid from the federal government.

- Careful consideration of the data, however, reveals an inconsistency with historical trends large enough to bring into question any conclusions, making it difficult to gauge the pandemic’s true toll on hunger levels.

- One of the more perplexing and historically inconsistent findings in the data from the past year is that food insufficiency appears to have risen as the unemployment rate fell.

- While it may be that the generosity of the enhanced unemployment benefits, which effectively provided a higher income for many than when they were working, made food more difficult to buy when they returned to work, it may also be that the data are simply unreliable.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has caused numerous challenges beyond the virus’s health effects. One of the commonly reported adverse impacts is rising hunger, yet this impact is arising despite substantial financial aid from the federal government, including significantly enhanced nutrition assistance for low-income individuals. This paper analyzes the available data related to food insecurity and food insufficiency to gauge the severity of the pandemic’s impact, including how the current statistics compare with historical trends. This analysis reveals inconsistencies not easily explained simply by the toll of the pandemic. Rather, the best available data collected over the past year are not well-suited for comparison with historical data, making it difficult to assess how drastically food insecurity has risen and why.

For background on the differences among food insecurity, very low food insecurity, and food insufficiency, as well as historical trends, refer to this primer from the American Action Forum.

How has food insecurity changed during the COVID-19 pandemic?

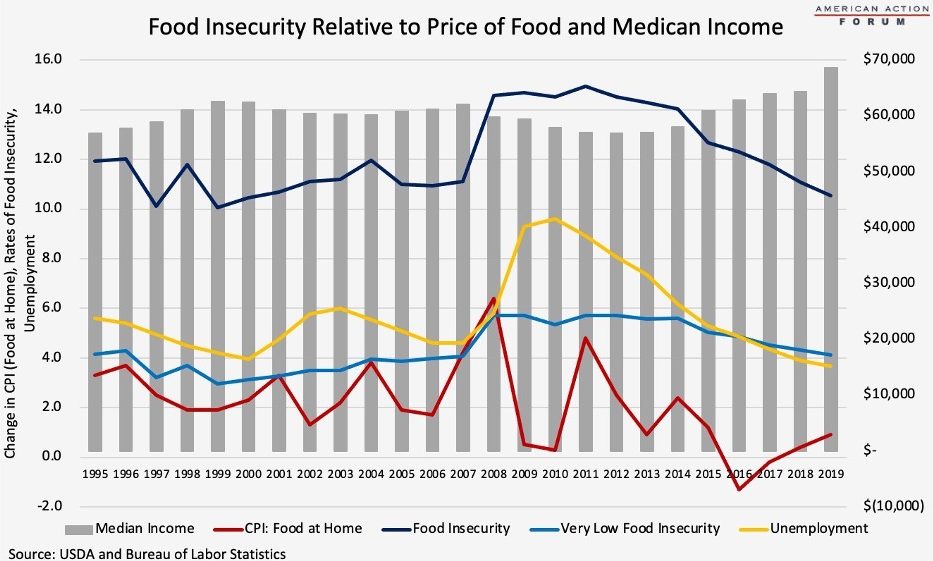

Food insecurity is highly correlated with financial challenges and the state of the economy. Prior to the pandemic, food insecurity had been steadily declining since 2014, with 10.5 percent of Americans classified as food insecure in 2019 and 4.1 percent considered to have very low food security, as shown in the chart below. These estimates are based on the annual Current Population Survey Food Security Supplement (CPS-FSS), conducted by the Census Bureau each December, asking a nationally representative sample of respondents about their access to food over the past year.

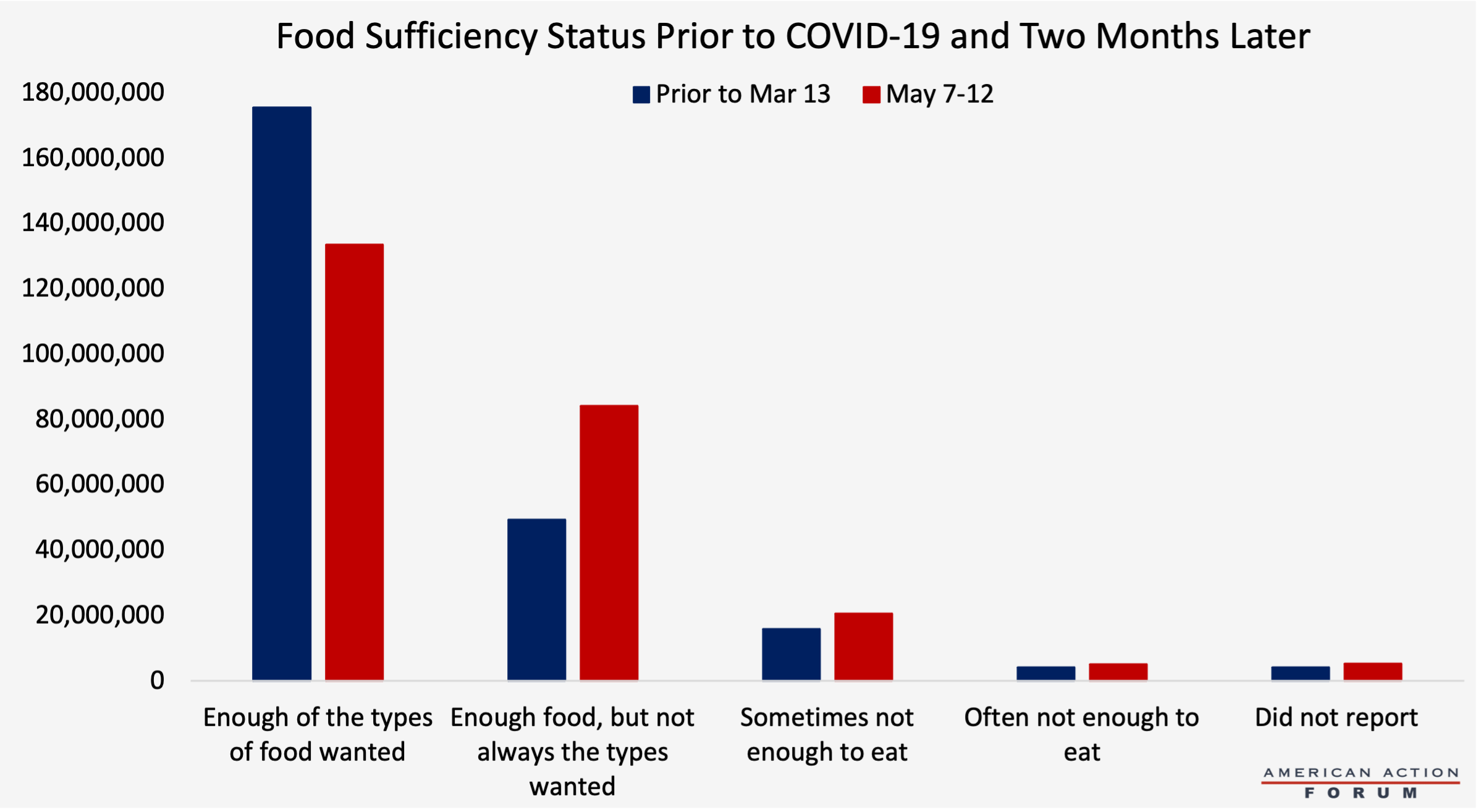

Since the start of the pandemic, the Census Bureau has attempted to capture changes in household situations in close to real time, including whether or not people have enough to eat. Based on the first biweekly Census Household Pulse Survey (HPS), conducted from April 23 to May 5, 2020, of a nationally representative sample, 175.5 million people—roughly half the country—had enough of the types of food wanted prior to March 13, 2020 (the day the United States declared COVID-19 a national emergency), and 8.1 percent (representing 20 million) reported food insufficiency (sometimes or often not having enough to eat). Two months later (according to the results of the May 7-12 survey), the share of people reporting having enough of the types of food wanted fell 24 percent, while the number reporting “sometimes” or “often” not having enough to eat increased by 31 percent and 22 percent, respectively.

These data should be interpreted cautiously. Note that the 8.1 percent of people who reported food insufficiency prior to March 13 is nearly double the 4.1 percent rate of very low food security reported in 2019. Further, when including those who stated they had “enough food, but not always the types wanted,” 27.9 percent would be considered food insecure; this figure is nearly triple the 10.5 percent rate found by the CPS-FSS in 2019. Given the downward trajectory that had persisted since 2014, it seems unlikely that food insufficiency or insecurity would climb that much prior to the pandemic and any real change in the economic situation. While it has been noted that food insufficiency and very low food security are defined somewhat differently, this level of inconsistency suggests a fundamental difference in the surveys, whether in the way the questions are being asked or answered or in the method by which data are being collected and results interpreted.

The data from during the pandemic provide more somewhat puzzling trends. Over the course of the year, the surveys indicate that overall food insufficiency increased even as unemployment reached its lowest levels since the start of the pandemic, particularly in November and December. Granted, this rise in food insufficiency is only true for those who reported a loss in employment income, as shown in the chart below, despite unemployed individuals still receiving an extra $400 per week in unemployment compensation at that time, as they had been since August. The share of respondents reporting food insufficiency but no loss in income remained relatively constant throughout the year, consistently accounting for roughly 2.5 percent to 3.0 percent of all respondents and between 4.5 percent and 5.5 percent of those reporting no loss in income. One possible explanation for the rise in food insufficiency toward the end of the year may be that money for food began competing with other expenses that were suddenly increasing in the fall, such as heating costs as the weather began to cool or holiday gifts in December. Regardless of reason, the survey responses show that food insufficiency reached as high as 20 percent among people with a loss in employment income and 12 percent overall in December, despite unemployment reaching its lowest point since April, another inconsistency with historical trends.[1]

Perhaps the generosity of the unemployment benefits—which for 50 percent of American workers provided greater income than they had received from their paychecks—resulted in many people having less money to purchase food upon returning to work relative to when they were collecting unemployment benefits. If they are returning to work when other expenses are higher (e.g. later in the fall as temperatures drop), the combination of higher costs and lower income could lead to greater food insecurity.

Also shown is the much higher number of people who reported that it was “somewhat” or “very difficult” paying for usual household expenses (this question was not asked in the first few months the survey was conducted). The discrepancy between the number of people reporting difficulty paying usual expenses and those reporting not having enough to eat suggests that people tend to prioritize the purchase of food or typically found sufficient means of assistance in acquiring food.

Feeding America’s estimates of food insecurity during the pandemic are based on a formula derived from historical data, heavily reliant on changes in the unemployment and poverty rates.[2] Their estimates from between March and May 2020 projected food insecurity would increase over the course of the pandemic between 1 percentage point (3.3 million individuals) and 5.2 percentage points (17.1 million individuals), depending on how the economy fared. With unemployment spiking an estimated 10 percentage points from March to April, food insecurity would have risen even more at the outset than its worst–case scenario predicted, reaching close to 20 percent. Feeding America’s October update estimates that the 2020 food insecurity rate will average 15.6 percent. Again, because food insecurity is not the same as food insufficiency, it is hard to compare its estimates to the findings of the HPS data, but an average of 37.3 percent of HPS respondents stated they either sometimes or often did not have enough to eat or had enough food, but not always the type wanted—2.5 times more than Feeding America’s estimate of food insecurity.

What do changes in SNAP and WIC participation reveal?

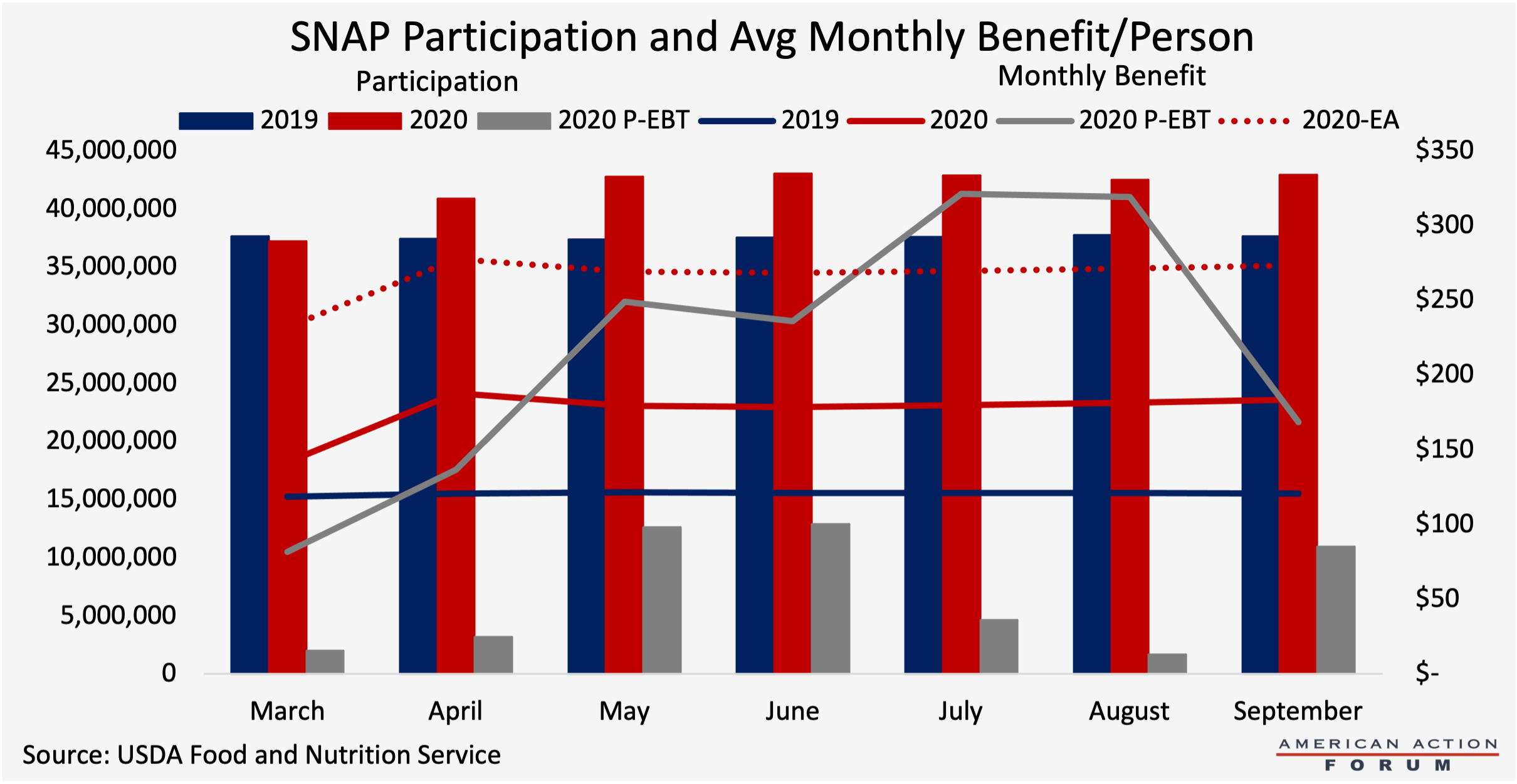

The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) is the largest food assistance program in the United States. As eligibility for the program is based on income, participation naturally would be expected to increase during an economic decline that results in many people losing their income, such as what happened during the COVID-19 pandemic. As the chart below shows, the data followed the expected trend. From March to April, as unemployment skyrocketed, SNAP participation increased 3.6 million, or 10 percent. The benefit level also increased dramatically, climbing 32.5 percent from March to April, as a result of legislative changes included in the Families First Act to provide more generous benefits during the crisis. The December relief package included a 15 percent benefit increase from January through June 2021.

In addition to the enhanced SNAP benefit payments, Congress also provided emergency nutrition assistance allotments worth $14.6 billion and to 23.2 million people per month from March through September 2020, averaging $90 per person per month in additional benefits (as shown by the dotted line in the chart above).[3] These emergency allotments allowed individuals who were not receiving the maximum benefit (which has been temporarily increased) to do so. Further, the newly established Pandemic Electronic Benefit Transfer (P-EBT) program provided nutrition funding for children who would have received free or reduced-price lunches at school, had their schools been open. An additional $10.7 billion in benefits was provided under this emergency program from March through September 2020 for an average of 6.9 million children per month, as shown in the chart above.[4] President Biden signed an executive order to increase the P-EBT amount by 15 percent on January 22, 2021.

In addition to the enhanced SNAP benefit payments, Congress also provided emergency nutrition assistance allotments worth $14.6 billion and to 23.2 million people per month from March through September 2020, averaging $90 per person per month in additional benefits (as shown by the dotted line in the chart above).[3] These emergency allotments allowed individuals who were not receiving the maximum benefit (which has been temporarily increased) to do so. Further, the newly established Pandemic Electronic Benefit Transfer (P-EBT) program provided nutrition funding for children who would have received free or reduced-price lunches at school, had their schools been open. An additional $10.7 billion in benefits was provided under this emergency program from March through September 2020 for an average of 6.9 million children per month, as shown in the chart above.[4] President Biden signed an executive order to increase the P-EBT amount by 15 percent on January 22, 2021.

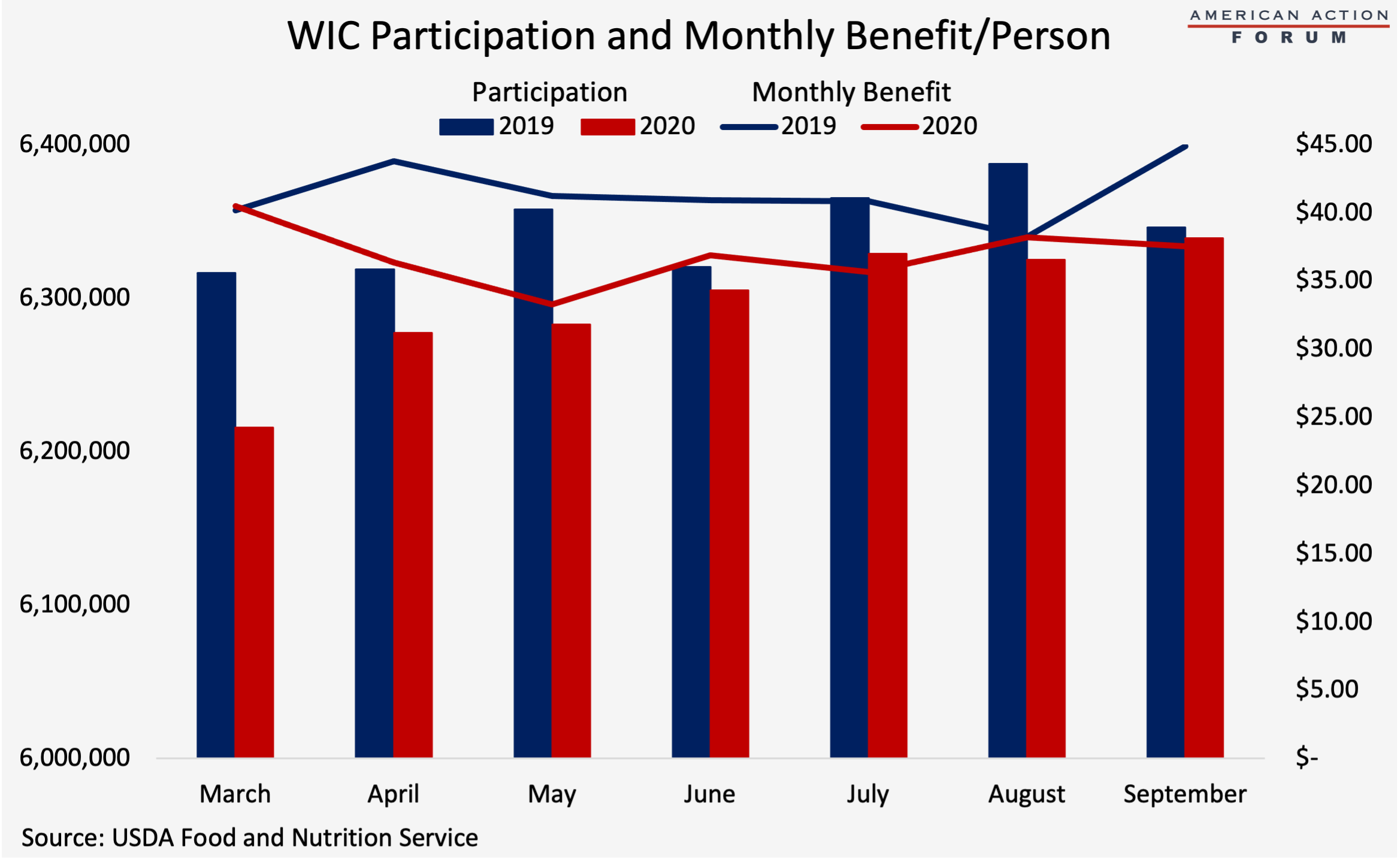

While SNAP participation and benefit levels significantly increased in 2020, participation and benefits levels in the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) declined, relative to 2019.[5] WIC provides nutrition assistance to pregnant and postpartum women and children up to age 5 through an annual appropriation from Congress. It is unclear why participation declined, but it may be that fewer low-income women are becoming pregnant during the pandemic. Recent reports from five states show that the once-anticipated “Coronavirus Baby Boom” turned out to instead be a bust, with birth rates down significantly compared with a year ago.[6]

As noted earlier, the number of people who reported sometimes or often not having enough to eat increased by roughly 6 million from March to May. So why did 2.4 million fewer people sign up for SNAP or WIC than reported going hungry? It may be because they were not eligible or did not know they were eligible. In fact, the generosity of the unemployment benefits that have been provided throughout the pandemic may have kept many unemployed individuals from being eligible for SNAP since the value of those benefits is counted as income when determining eligibility. Further, it is not known whether some of those reporting not having enough to eat were receiving SNAP or WIC benefits.

Historical data show that not everyone eligible for SNAP tends to participate, particularly those with some earned income: In 2017, 84 percent of eligible individuals nationwide participated, while only 73 percent of the eligible “working poor” did so.[7] For those who do participate, SNAP benefits are relatively low and beneficiaries may still have difficulty affording a sufficient amount of healthy food. SNAP requires beneficiaries to cover 30 percent of their expected food costs, based on the Department of Agriculture’s analysis of how much food should cost. This analysis is based on the Thrifty Food Plan (TFP), but numerous studies have identified myriad flaws with the TFP, including that the true cost of food and meal preparation is significantly underestimated, often resulting in inadequate benefits.

Additional Challenges with the Data

In surveys that rely on the respondents’ own accounting of their past experience, the respondents can interpret the questions or their own experience inconsistently, leading to inconsistency in the results. If respondents feel their experience does not neatly fall into a given answer choice, some will choose to “round up” while others will “round down.” Further, comparing responses from an annual survey (the CPS-FSS) that asks respondents to consider their experience over the past year with a survey asking respondents about their experience over the past few weeks may be impacted by recall bias, which makes people more likely to remember recent events and to feel their effect more strongly than they might remember experiences further in the past. The overall effects of the pandemic may also be playing a role in how people respond to these specific questions: The myriad stressors presented by the pandemic may be causing a confounding bias that leads to people feeling as though obtaining sufficient food has been more difficult lately because everything, generally, has been (or at least has felt) more difficult. Moreover, the figures provided above have been estimated based on the responses of a much smaller (and inconsistently sized) representative sample, with response rates as low as 1 percent and only twice reaching as high as 10 percent. While extrapolation is a common statistical method for estimating outcomes for a larger population based on those of a smaller subpopulation, it is not imperfect.

Conclusion

Prior to the pandemic, food insecurity was relatively low and falling. With millions of people losing their jobs during the pandemic, one would expect food insecurity rates to rise given the correlation between food security and income. In an effort to prevent that from happening, Congress quickly passed numerous relief measures that included direct payments, enhanced unemployment benefits, and more generous nutrition assistance than had ever before been provided. Nevertheless, despite the trillions of dollars in assistance provided over the past year, reports of rising food insecurity persist. A closer look at the data, however, reveal sharp inconsistencies with historical trends, making it difficult to assess the true toll of the pandemic on food insecurity and insufficiency in the United States. Most surprising is the alleged rise in food insufficiency as the unemployment rate has fallen. It is unclear if the number of individuals without enough to eat is truly rising, particularly at the rate indicated, or if the data are unreliable.

[1] https://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/empsit.pdf

[3] https://www.fns.usda.gov/data/january-keydata-report-september-2020-data

[4] https://www.fns.usda.gov/data/january-keydata-report-september-2020-data

[5] https://www.fns.usda.gov/data/january-keydata-report-september-2020-data

[7] https://fns-prod.azureedge.net/sites/default/files/resource-files/Reaching2017-1.pdf