Research

March 10, 2021

PRIMER: The Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC)

Executive Summary

- The Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) is a federally funded, state-administered nutrition assistance program for low-income and nutritionally at-risk women, infant, and children.

- WIC provides assistance in the form of financial benefits to purchase nutritionally rich food and infant formula, as well as educational services and materials.

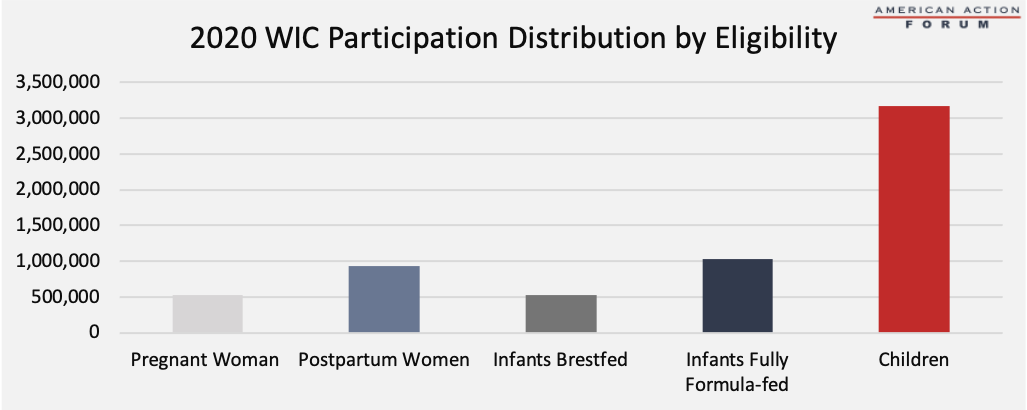

- WIC participation has been steadily declining over the past decade as the economy has improved since the Great Recession, but children have consistently accounted for roughly half the beneficiaries while pregnant and postpartum women and infants account for roughly equal shares of the other half.

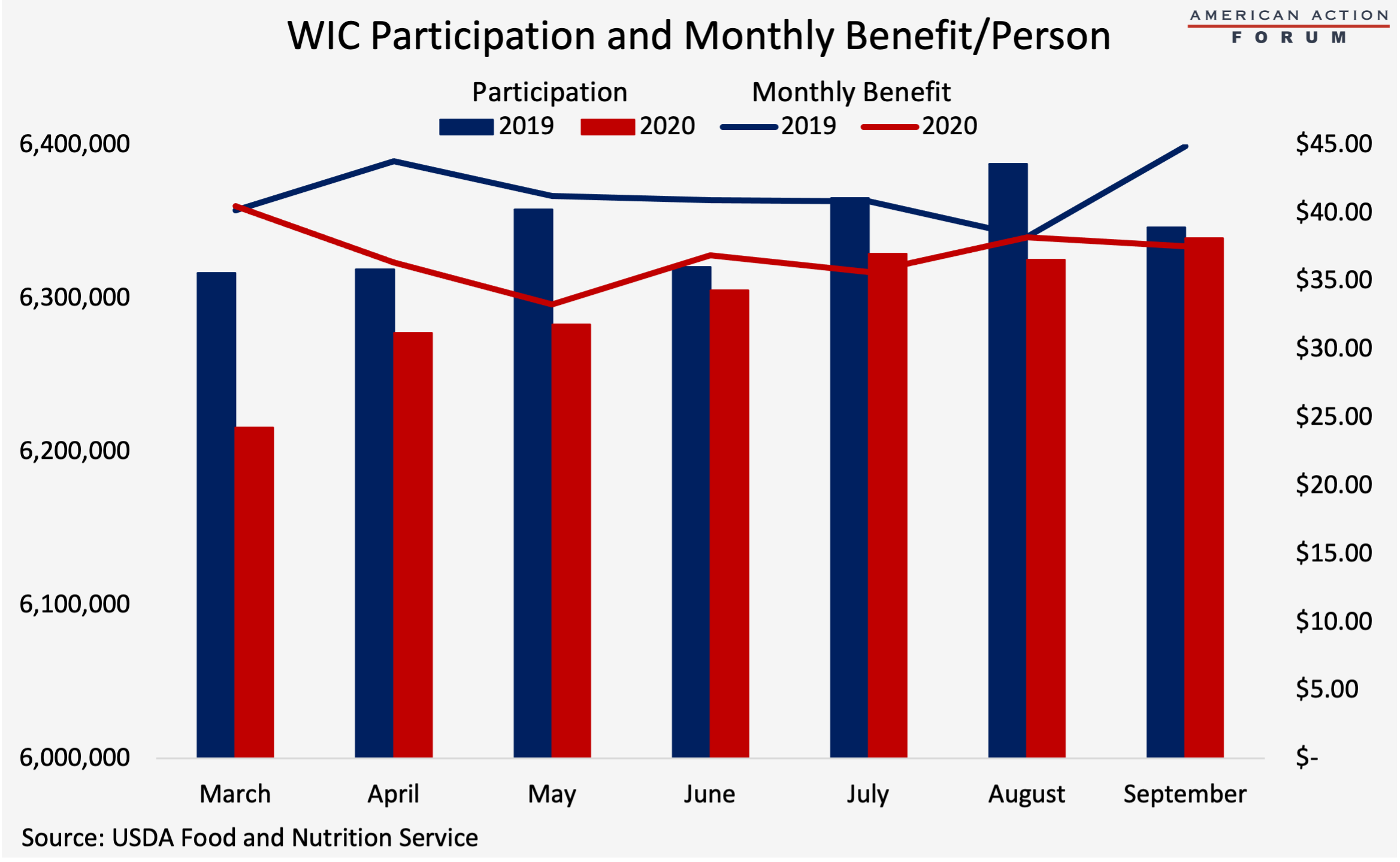

- Despite the COVID-19 pandemic, WIC participation and benefits in 2020 were slightly below those of 2019; this may be because the anticipated “baby boom” has not occurred and fewer low-income women have become pregnant relative to years past.

Introduction

Established as a pilot program in 1972, the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) was made a permanent federal program in 1974.[i] Like the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), it is administered at the federal level by the Food and Nutrition Service in partnership with the states. State agencies are responsible for assessing participant eligibility and providing benefits and services. WIC provides federal grants to states for supplemental foods, health care referrals, and nutrition education for low-income pregnant and postpartum women, and to infants and children up to age five who are found to be at nutritional risk. Participants receive checks, vouchers, or Electronic Benefit Transfer (EBT) cards to purchase specific foods from approved retailers, such as grocery stores or farmers’ markets. WIC is a short-term program and participants typically lose eligibility after six months to a year. Participants must then reapply to the program if they would like to continue receiving the benefits and services.

Eligibility

To be eligible to participate in WIC an individual must meet the categorical requirement for women or the age requirement for infants and children, as well as residential, nutrition risk, and income requirements. Women must either be pregnant, postpartum (up to six months after the birth of the infant or the end of the pregnancy), or breastfeeding (up to the infant’s first birthday). Infants are eligible up to their first birthday and children, after their eligibility is reestablished, are eligible up to their fifth birthday.[ii] The residential requirement mandates that applicants live in the state in which they apply, though they are not required to live there for any minimum length of time. Programs are available in all 50 states, 34 tribal organizations, the District of Columbia, and five U.S. territories.

“Nutrition risk” is defined as an individual who has medical or dietary-based conditions. To determine nutritional risk, applicants must be evaluated by a health professional, such as a physician, nurse, or nutritionist, and diagnosed with one of the following: anemia, underweight, poor diet or history of poor pregnancy outcome. This evaluation can be done at a WIC clinic at no cost to the applicant or at any doctor’s office.

Each state may set its own income limit within the range dictated by the federal government: between 100 and 185 of the federal poverty level (FPL).[iii] Because the federal government covers the full cost of benefits without any requirement of state matching funds, every state uses the maximum benefit level of 185 percent FPL. If a woman or her family receives SNAP benefits, Medicaid, or Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF), they may be (depending on the state) automatically deemed eligible for WIC through a process known as adjunctive eligibility.

If WIC agencies do not have enough funding to provide benefits to all eligible individuals, a priority system based on those with the most serious conditions is used to determine placement on the waiting list. Of late, however, Congress has sought to ensure that all eligible individuals have access to benefits by providing funding based on expected participation.[iv]

Benefits

WIC provides various types of benefits to help pregnant women, new parents, and young children eat well and stay healthy. Each month, WIC gives participants either vouchers or EBT cards to purchase at no cost to them specified amounts of foods rich in protein, calcium, iron, vitamins A and C, and other important nutrients. Such foods include milk, cheese, breakfast cereal, eggs, whole wheat bread, brown rice, peanut butter, canned fish, and legumes.[v] There are seven food packages for which a beneficiary may be eligible which determines the specific foods they may purchase. Previously, if a beneficiary was using a paper voucher, all items in the monthly food package for which a beneficiary is eligible had to be purchased in a single visit.[vi] For example, if a beneficiary is eligible for milk, eggs, cereal, and peanut butter, but only purchases milk, eggs, and cereal, they would not be able to later purchase peanut butter that month. As of October 1, 2020, all states were required to upgrade their systems to use EBT cards, allowing beneficiaries to purchase eligible foods during multiple visits throughout the month, as the electronic system is capable of tracking purchases and redeemed benefits.[vii]

Eligible children and women are also given $8 and $11 vouchers, respectively, to buy fruits and vegetables each month as part of their monthly benefits, which may also be used at farmers’ markets. WIC supplies formula for babies up to 11 months, and infant cereal, food, fruits and vegetables for babies six-11 months.[viii] In order to save money, states restrict qualifying foods to specific low-cost brands or require rebates for items, particularly infant formula.[ix]

Additionally, WIC provides services such as breastfeeding education and support for expectant and postpartum mothers; nutrition education and counseling; and screening referrals to other health, welfare, and social services.[x]

Participation

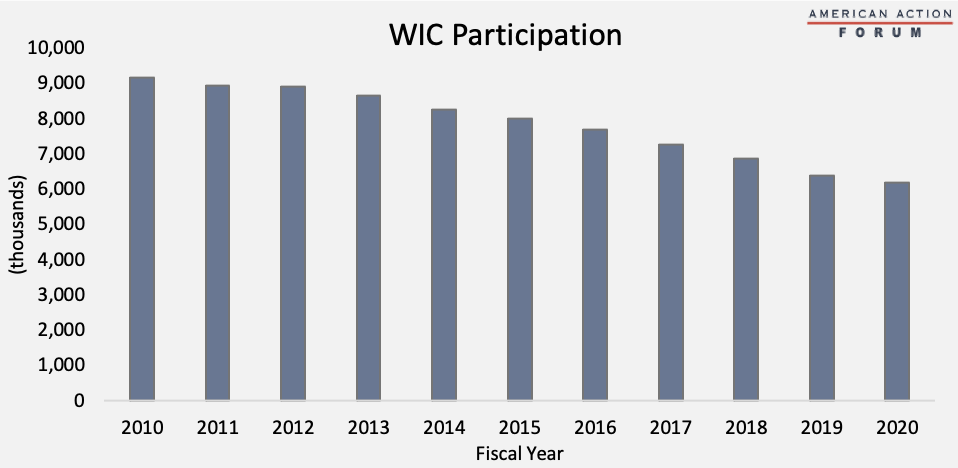

Over the past decade, WIC participation has steadily declined from a high in 2010 of 9.2 million to a low in 2020 of 6.2 million.[xi]

In 2020, 1.5 million women, 1.6 million infants, and 3.2 million children participated.[xii] The coverage rate—the share of eligible people who receive benefits—was highest among infants, with an estimated 80 percent of eligible infants participating, followed by 58 percent of one-year-olds, but dropping to just 25 percent of four-year-olds.[xiii] Participation is also much higher among non-breastfeeding women (96 percent) compared with just 56 percent of eligible postpartum women who are breastfeeding (56 percent), likely because of the cost burden of formula needed by non-breastfeeding women.[xiv]

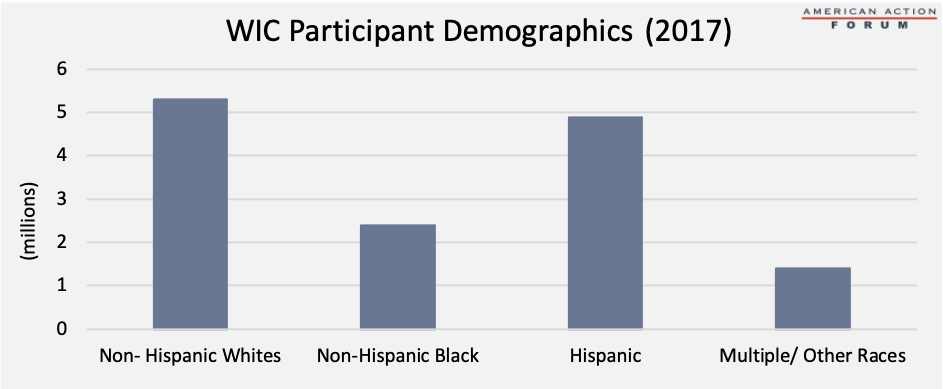

In 2017, WIC participants included 5.3 million non-Hispanic White people, 4.9 million Hispanic individuals, 2.4 million non-Hispanic Black people, and 1.4 million who identify as other or multiple races.[xv] The coverage rate is about the same for non-Hispanic Black people (59 percent) and Hispanic people (60 percent).[xvi] The coverage rate is estimated at 41 percent for non-Hispanic White people and 43.7 percent for people who identify as another race or multiple races.

Costs

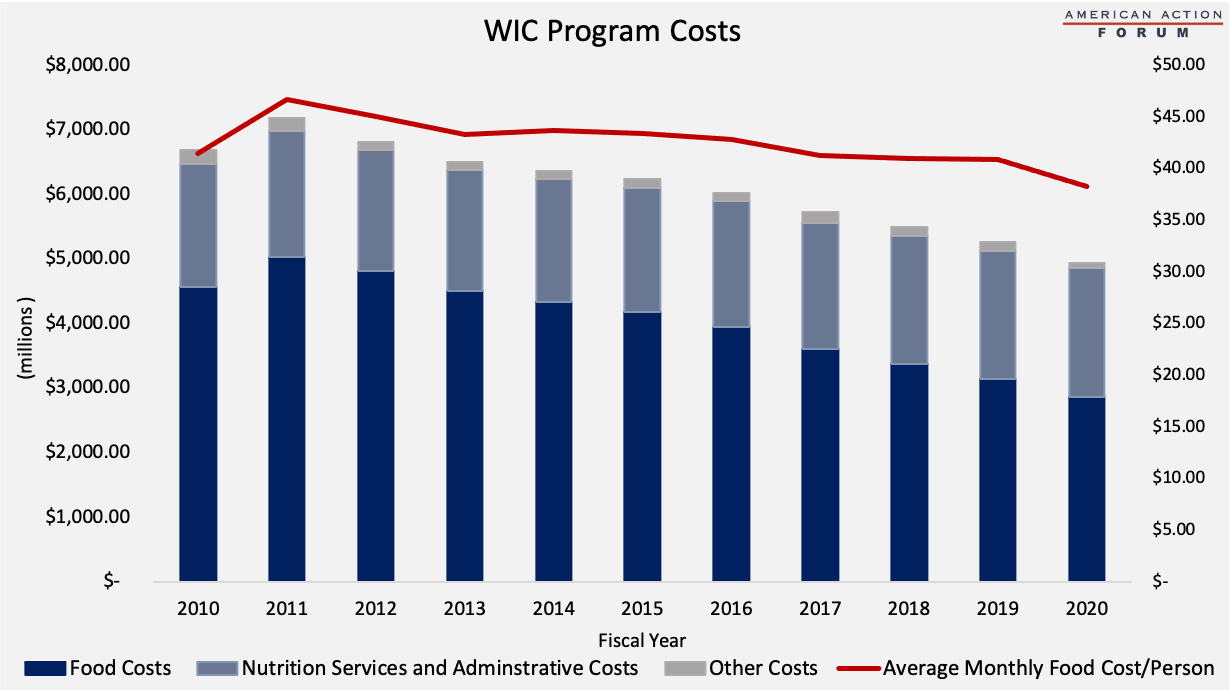

An annual appropriation from Congress controls WIC program costs. A formula is used to distribute funds to states based on expected need.[xvii] Program costs are primarily driven by participation rates; spikes in food costs can, however, have a significant impact, as happened in 2011 (shown here). As such, over the past decade, program costs were highest in 2011 at $7.2 billion and lowest in 2020 at $4.9 billion.[xviii] Per-person, per-month food benefits have averaged $42.50 over the past decade, reaching nearly $47 in 2011 and dropping to $38 in 2020.[xix]

WIC During the COVID-19 Pandemic

While SNAP participation and benefit levels significantly increased in 2020, WIC participation and benefits levels declined relative to 2019.v It is unclear why participation declined, but it may be that fewer low-income women are becoming pregnant during the pandemic. Recent reports from five states show that the once-anticipated “Coronavirus Baby Boom” turned out to instead be a bust, with birth rates down significantly compared with a year ago.vi

[i] https://www.fns.usda.gov/wic/about-wic-wics-mission

[ii] https://www.fns.usda.gov/wic/wic-eligibility-requirements

[iii] https://www.fns.usda.gov/wic/wic-eligibility-requirements

[iv] https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R44115

[v] https://www.benefits.gov/news/article/391

[vi] https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R44115

[vii] https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R44115

[viii] https://www.fns.usda.gov/wic/wic-food-packages-maximum-monthly-allowances

[ix] https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R44115

[x] https://www.fns.usda.gov/fmnp/overview

[xi] https://fns-prod.azureedge.net/sites/default/files/resource-files/37WIC_Monthly-1.pdf

[xii] https://fns-prod.azureedge.net/sites/default/files/data-files/Keydata-September-2020.pdf

[xiii] https://www.fns.usda.gov/wic-2017-eligibility-and-coverage-rates

[xiv] https://www.fns.usda.gov/wic-2017-eligibility-and-coverage-rates

[xv] https://www.fns.usda.gov/wic-2017-eligibility-and-coverage-rates

[xvi] https://www.fns.usda.gov/wic-2017-eligibility-and-coverage-rates

[xvii] https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R44115

[xviii] https://fns-prod.azureedge.net/sites/default/files/resource-files/wisummary-1.pdf

[xix] https://www.fns.usda.gov/pd/supplemental-nutrition-assistance-program-snap