Weekly Checkup

February 19, 2021

COVID-19, Medicaid Expansion, and the Unfinished Business of the ACA

The Weekly Checkup has already considered the American Recovery Plan’s COBRA subsidy and premium tax credit expansion, so this week let’s turn to its changes to Medicaid. As I detailed recently, congressional Democrats and the White House are working to include as much of the president’s broader agenda as possible in the reconciliation legislation because it is not subject to a filibuster in the Senate and thus can be passed on a party-line vote. As a result, a package that is touted as a response to the pandemic includes myriad provisions unrelated to COVID-19. The bill’s Medicaid provisions run the gamut from clearly pandemic-related to obviously unrelated.

For example, under current law drug manufacturers can be required to pay penalties to state Medicaid programs if they raise the price of their drugs faster than the rate of inflation. But these rebates can quickly compound such that the manufacturers could be required to pay more to the state in rebates than the state paid for the drug to start with. Since 2009, these rebates have been capped at 100 percent of the cost of the drug to prevent that from happening. The reconciliation bill would remove this cap beginning in 2023, allowing manufacturers to be forced to pay states to use their drugs. This provision would punish drug manufactures, who are a favorite target of progressives, as well as generate extra money to spend—since apparently $1.9 trillion in spending wasn’t sufficient on its own. Neither of these objectives have anything to do with COVID-19.

On the other hand, proposed changes to allow Medicaid to cover prison inmates’ health care during their last 30 days of incarceration could help address gaps in coverage that often accompany an inmates’ release from prison prior to reenrolling in Medicaid. While this isn’t exclusively related to the pandemic, ensuring seamless health coverage during the pandemic makes some sense, although it’s not clear why this temporary policy needs to continue for five years.

While there are a number of other Medicaid-related provisions you can read about here, the most significant changes related to the Affordable Care Act’s (ACA) Medicaid expansion. Back in 2012, the Supreme Court ruled that the federal government could not force states to expand Medicaid to 138 percent of the federal poverty level (FPL), as the law originally aimed to do. The ACA’s premium subsidy structure assumed Medicaid expansion, however, and as a result roughly 2.2 million people who make below 100 percent FPL and reside in non-expansion states are not eligible for either Medicaid or ACA subsidies. ACA supporters have long been working to cajole states that have not expanded eligibility to do so. To date, 12 states still have not expanded. Under current law, the federal government pays 90 percent of the cost of care for the expansion population, and from 56.2 percent to a high of 81.2 percent of the cost for states’ traditional Medicaid population.

As an incentive for states to expand their Medicaid programs, under the reconciliation bill any state that expands its Medicaid program will receive a 5 percent increase in the federal contribution for its traditional Medicaid population for two years. This increase would be in addition to the 6.2 percent increase in the federal contribution to state Medicaid costs included in the Families First Coronavirus Response Act for the duration of the public health emergency declaration. The argument is that expanding Medicaid coverage is crucial to ensuring all Americans can receive care for COVID-19. This legislation, however, already would allow states to cover COVID-19 related treatment, testing, and vaccination at no cost for any uninsured individual by promising 100 percent federal reimbursement for those costs. Enrollment in Medicaid isn’t necessary to cover COVID-19 costs.

This provision is really about the unfinished business of the ACA’s Medicaid expansion. Ironically, while Biden’s proposed ACA subsidy enhancements would allow even billionaires to receive subsidized ACA coverage, getting states to expand Medicaid would actually strip people between 100 percent and 138 percent of FPL of the subsidized coverage they have right now and instead force them into Medicaid. At least Biden isn’t promising that if they like their plan, they can keep their plan.

Video: The ACA’s Insurance Subsidies

AAF’s Christopher Holt explains why the Biden Administration’s proposal to change ACA insurance subsidies under the American Recovery Plan is not an appropriate response to COVID-19.

Tracking COVID-19 Cases and Vaccinations

Ashley Brooks, Health Policy Intern

To track the progress in vaccinations, the Weekly Checkup will compile the most relevant statistics for the week, with the seven-day period ending on the Wednesday of each week.

| Week Ending: | New COVID-19 Cases: 7-day average |

Newly Fully Vaccinated: 7-Day Average |

Daily Deaths: 7-Day Average |

|

Feb. 17, 2021 |

77,385 |

499,555 |

2,708 |

|

Feb. 10, 2021 |

102,530 |

625,844 |

2,975 |

|

Feb. 3, 2021 |

134,029 |

433,486 |

3,001 |

|

Jan. 27, 2021 |

161,534 |

302,261 |

3,285 |

Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Note: The U.S. population is 330,089,706.

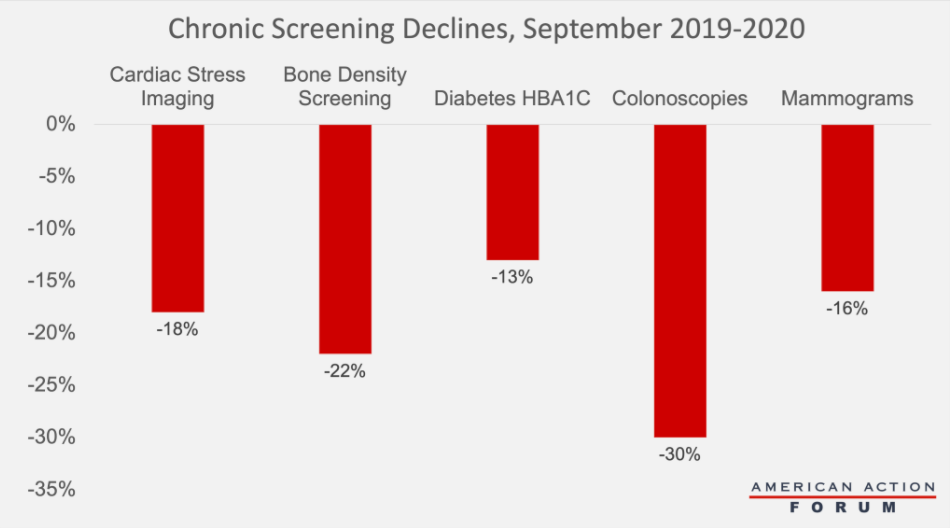

Chart Review: Delayed and Forgone Care as a Result of COVID-19

Madeline VanHorn, Health and Human Welfare Policy Intern

One widely reported effect of the pandemic is a widespread deferral of care. As shown in the chart below using data from over 900 hospitals across the United States through September 2020, screenings for many common health conditions were far below 2019 levels. Nearly 36 percent of adults reported delaying or forgoing some sort of health care by September 2020. Over 75 percent of these people possessed chronic health conditions such as diabetes, hypertension, heart disease, cancer, and kidney disease. Physicians warn that delayed or forgone care, especially for those with chronic conditions that require careful monitoring, can lead to rapid health deterioration. Of those who delayed care, 17 percent reported that it worsened one or more of their health conditions. A prolonged avoidance of care could mean delay of diagnosis of new conditions, more long-term health concerns, and increased deaths unattributed to COVID-19. While patient volumes rose and health services spending began to rebound in Q3 of 2020, there is concern that the decline in health care utilization during the pandemic will result in sicker patients and costlier care throughout 2021.

Source: Healthcare Financial Management Association

From Team Health

Has COVID-19 Vaccine Distribution Been Equitable? – Director of Human Welfare Policy Tara O’Neill Hayes

A close look at the data around vaccine distribution undermines any easy narrative of an inequitable distribution of the COVID-19 vaccine.

Daily Dish: Equity and COVID-19 Vaccination – AAF President Douglas Holtz-Eakin

The equitable distribution of vaccines is a difficult issue to grasp and address.

Worth a Look

Kaiser Health News: Medicare Cuts Payment to 774 Hospitals Over Patient Complications

Fierce Healthcare: Hospital admissions down 8.2% from March to December 2020 due to COVID-19