Weekly Checkup

July 8, 2022

Never Say Die

If you’ve recently been feeling stuck in a time loop, where events just repeat themselves endlessly, you’re not alone. Congressional leadership has decided, once again, to try to pass legislation using the fast-track reconciliation process. This includes the Senate Finance Committee’s latest attempt at price controls for prescription drugs covered under Medicare. There have been some changes since the committee’s last drug pricing proposal as part of the Build Back Better Act, some large and some small.

To start, the new legislation includes timing changes. Implementation dates for “negotiations” (price controls), applicability periods, effective dates for new prices and the Part D redesign and the like would be pushed back a year, because that’s how long Congress has been talking about this proposal but not voting on it. Of note, negotiation on biologics would be delayed longer than negotiation for other drugs – reflecting the expectation that more biosimilars will be coming out in the next couple of years. If a biosimilar fails to enter the market during the delay period, however, the biologic manufacturer would be penalized and owe Medicare a rebate.

The legislation also firms up the language around the number of drugs for which the Department of Health and Human Services secretary must dictate prices. The new language sets a requirement for 10 drugs in Part D to be negotiated in 2026, 15 for Part D in 2027, 15 for Parts D and B in 2028, and 20 in Parts D and B in 2029. The legislation also clarifies that manufacturers would not be required to provide price concessions that exceed the lower end of a drug’s 340B price or the Medicare-negotiated price.

Most of the legislation’s Part D section is in line with previous iterations; while the timing has changed by a year, it pushes the $0 out-of-pocket maximum cap in the catastrophic phase, to 2024, and the $2,000 per-year cap on total out-of-pocket spending to 2025. Changes were made to expand the Part D low-income subsidy from 135 percent to 150 percent of the federal poverty level, while premium growth would be capped at 6 percent per year through 2029 instead of 4 percent through 2027. The repeal of the rebate rule would be pushed back yet again to January 2027.

Perhaps the most notable difference between this legislation and its previous iterations is that the insulin provisions were taken out, meaning there wouldn’t be a $35 out-of-pocket insulin cap. Reportedly, the insulin provision was removed in anticipation of bipartisan legislation spearheaded by Sens. Susan Collins (R-ME) and Jeanne Shaheen (D-NH). This reversal is surprising, because while the policy itself is flawed, capping patients’ out-of-pocket insulin costs at $35 is a particularly popular proposal. Thus, removing the provision is a bit of a gamble: The Shaheen-Collins legislation needs 60 votes to pass, which it almost certainly does not have. Moreover, the legislation’s insulin provision was never its most controversial. That prize goes to its “negotiation” policies, which could be summarized as “we tell you what price we’re going to pay, and you can take it or get shut out of the market.” Such tactics are fundamental to this legislation but also represent the legislation’s biggest problem, and very much remain so in this latest iteration.

All in all, despite a year’s worth of debate, this legislation ended up looking very similar to last year’s version – except without one of its most popular provisions. The hardball negotiation framework remains in place, the Part D reforms are mostly the same (for a better way to do Part D reform, check out previous American Action Forum research here), and this legislation’s political chances look about as good as they did last year.

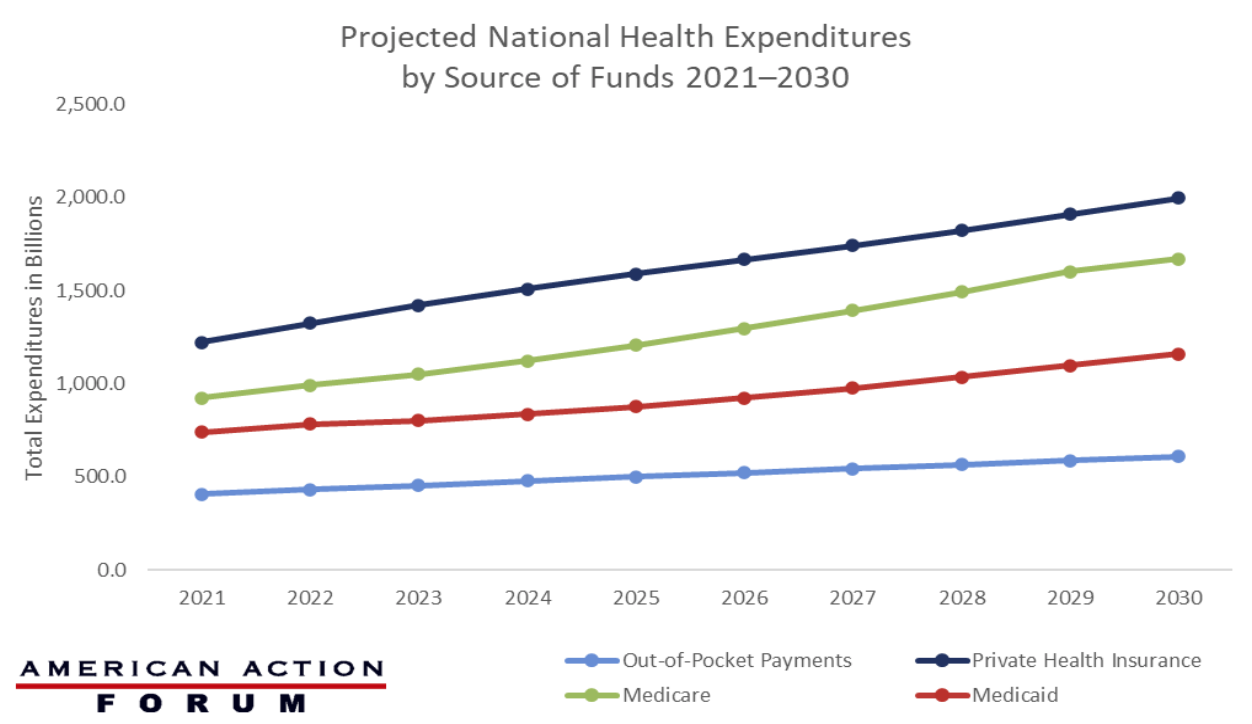

Chart Review: National Health Expenditures Projected Annual Growth, 2021–2030

Evan Turkowsky, Health Care Policy Intern

According to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), the National Health Expenditure, a measure of total health care spending, both public and private, is projected to grow 5.1 percent per year from 2021–2030, reaching nearly $6.8 trillion by the end of that period. As seen in the chart below, the total expenditures of the four largest sources of health care funds are expected to grow through 2030, the last projected year available, with Medicare expenditures growing the fastest at 7.2 percent per year. Medicare expenditures will exceed the $1 trillion mark for the first time in 2023 ($1.1 trillion) and see an average 4.3 percent growth per year, reaching $1.7 trillion in 2030. This exponential growth will most likely start to plateau in 2029 with the last of the Baby Boomers enrolling in Medicare. Out-of-pocket payments are projected to grow at the slowest rate, at an average of 4.6 percent per year, with an overall growth of $203 billion from 2021–2030. Private health insurance expenditures are projected to grow at an average of 5.7 percent annually through 2030, driven by projected rebounds in utilization in 2021 and 2022. Finally, Medicaid expenditures are expected to grow at a rate of 5.6 percent per year through 2030.

Data Source: The CMS National Health Expenditure Projection Accounts