Weekly Checkup

March 19, 2021

Special Enrollment Periods and the ACA’s Stability

One of President Biden’s first acts upon taking office was to order a special enrollment period (SEP) giving individuals who had skipped insurance coverage through the Affordable Care Act’s (ACA) marketplaces during the December open enrollment period—or who lost their job in the intervening two months—a second chance. That SEP is ongoing, running from February 15 to May 15. This week, word leaked out that the Biden Administration is considering what you could call an extra special enrollment period—extending the current SEP beyond May. I’m on the record as believing that Biden’s SEP is relatively pointless and not particularly objectionable, but if market-wide SEPs were to evolve into a continual open enrollment period, there would be real risks to the health insurance market.

Recall that back when the ACA was passed, two key features were its guaranteed-issue requirement and protections for those with preexisting conditions. Insurers were required to sell to all comers, and they could no longer carve out coverage exemptions for pre-existing health conditions. The problem with these provisions is they opened the health care system to freeloading. Individuals could elect not to purchase insurance coverage, knowing that the insurer of their choice would have to sell them coverage later if they needed it. But for insurance to work, insurers need lots of healthy people paying premiums that can be used to cover the medical expenses of a smaller number of enrollees who need care. In a vacuum, policies like these would result in spiraling premiums as insurers tried to get sufficient revenue from a shrinking pool of enrollees. So the law’s authors also mandated that all Americans sign up for health insurance, established a penalty for those who didn’t, and limited signups to one open enrollment period prior to the start of each new plan year. There were SEPs built in for specific extenuating circumstances—birth of a child, change in employment, etc.—but for the most part, if you decided to roll the dice and skip coverage, you would pay a fine and be stuck waiting until the next year if you ended up needing coverage.

The individual mandate penalty was effectively unenforced in the early years of enactment, and now the penalty itself is set to zero. With the penalty for waiting to buy coverage gone, insurers largely depend on the threat that you’ll have to wait until the next plan year to sign up if you get sick. But if open enrollment now extends into the third quarter of the plan year, waiting doesn’t pose all that much of a risk.

The counter-argument for the extra SEP is that this is a unique situation, given the pandemic as well as the enhanced benefits that could make coverage cheaper than it was in December. But, if you haven’t noticed, the pandemic has been around for more than a year, and the current SEP will last more than two months past the enactment of the reconciliation bill. Given the left’s focus on expanding coverage above all else, future SEPs, perhaps tied to natural disasters or economic slowdowns, seem likely. But eventually these universal SEPs will impact premiums. The ACA’s premiums have been stabilizing in recent years, but policies that make freeriding easier will lead to higher premiums.

Advocates for the ACA aren’t particularly worried about higher premiums, because they’ve just increased federal subsidies. At some point, however, borrowing more money to subsidize ever-increasing premiums will become untenable. But there is a progressive solution for that as well: Medicare for All.

Video: Another Round of Reconciliation

Amid talks of another reconciliation bill, AAF’s Christopher Holt explains how federal reconciliation is more limited than it seems.

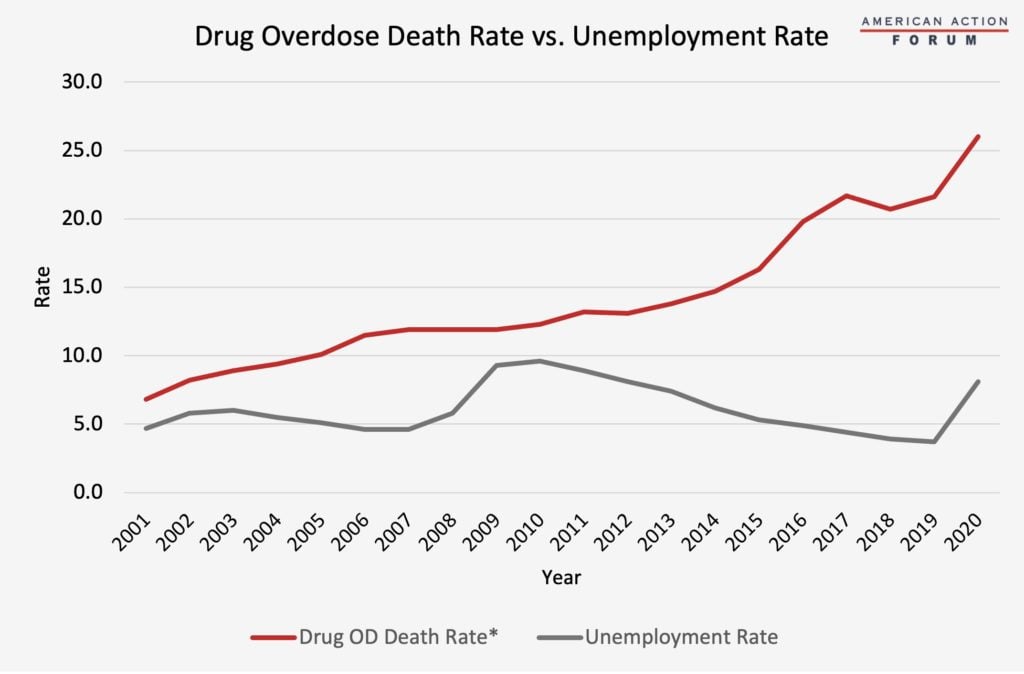

Chart Review: Drug Overdose Deaths and Unemployment

Alexis Williams, Human Welfare Policy Intern

Roughly 83,000 people died from a drug overdose between August 2019 and July 2020, the highest number recorded in a 12-month period, according to the data in the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s December report. Similarly, the average unemployment rate increased 4.4 percentage points from 2019 to 2020, primarily due to the pandemic. While the two points rose in tandem over the last year, the trends over the past two decades show no correlation, as the chart below shows. COVID-19 is an underlying factor that may have caused the rate of drug overdose deaths to increase along with the unemployment rate. The increase in drug overdose deaths over the past 10 years may be attributed to greater incidences of people experiencing poor mental health and suicidal thoughts. Overdose deaths could also be concentrated in areas with higher-than-average unemployment, such that unemployment is correlated with deaths at a more local level.

Sources: Bureau of Labor Statistics and the National Institute on Drug Abuse

Tracking COVID-19 Cases and Vaccinations

Ashley Brooks, Health Care Policy Intern

To track the progress in vaccinations, the Weekly Checkup will compile the most relevant statistics for the week, with the seven-day period ending on the Wednesday of each week.

| Week Ending: | New COVID-19 Cases: 7-day average |

Newly Fully Vaccinated: 7-Day Average |

Daily Deaths: 7-Day Average |

|

March 17, 2021 |

53,772 |

708,575 |

1,052 |

|

March 10, 2021 |

67,348 |

863,288 |

1,495 |

|

March 3, 2021 |

62,767 |

856,565 |

1,933 |

|

Feb. 24, 2021 |

66,324 |

800,377 |

2,062 |

|

Feb. 17, 2021 |

76,739 |

710,121 |

2,688 |

|

Feb. 10, 2021 |

103,585 |

667,986 |

3,010 |

|

Feb. 3, 2021 |

134,277 |

461,048 |

3,014 |

|

Jan. 27, 2021 |

161,865 |

321,493 |

3,297 |

Sources: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Trends in COVID-19 Cases and Deaths in the US, and Trends in COVID-19 Vaccinations in the US

Note: The U.S. population is 330,143,887.

Worth a Look

Reuters: Britain to slow vaccine rollout due to supply crunch in India, testing of big batch

Axios: FEMA to reimburse funeral costs for coronavirus victims