Testimony

March 29, 2017

Evaluating the Paperwork Reduction Act: Are Burdens Being Reduced?

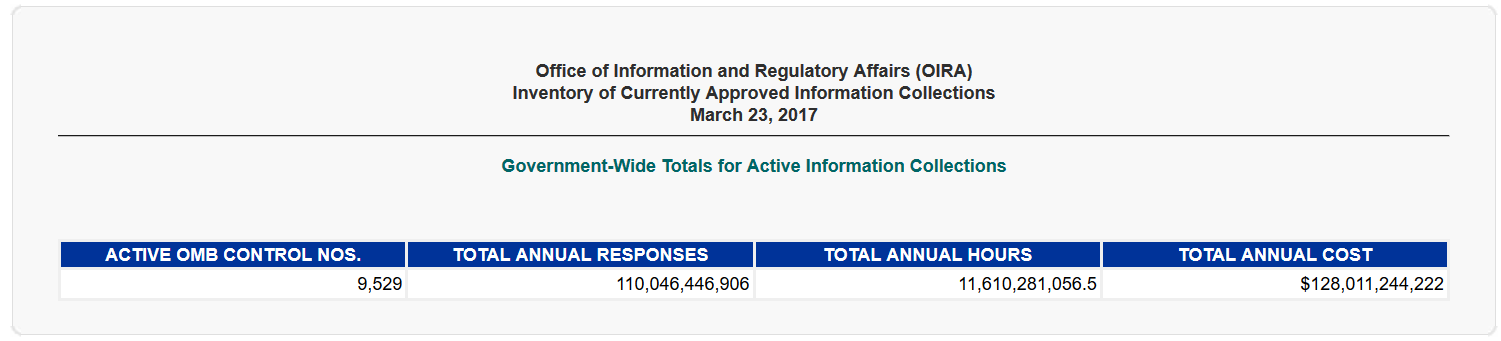

- The short answer to the title of this hearing is, no, burdens are not lower. In 1997, after amendments to the Paperwork Reduction Act (PRA), the cumulative burden was 6.9 billion hours. Today, it stands at 11.6 billion hours. Small businesses are particularly affected, with 3.3 billion hours of compliance burdens and $111 billion in costs.

- The figures above are shocking, but are they accurate? Many have referred to burden calculations as “artificial” or “pseudo-science.” The American Action Forum (AAF) has documented several instances of extreme calculation errors. Where there are mistakes, the PRA is also rife with missing cost data.

- The PRA suffers from historical mismanagement from federal agencies who routinely violate the law. Last fiscal year, the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs (OIRA) reported 283 violations, but there are no consequences for agency violations. Individual or business violations, however, can carry stiff penalties.

- Finally, there are several reform options for Congress as it examines updates to the PRA. Agencies could begin to monetize the costs of paperwork collections, meet targeted reduction goals from Congress, move more reporting requirements online, and foster greater public participation for new or major changes to an existing collection.

Let me provide additional detail on each in turn.

Growth in Federal Paperwork

Reducing the amount of paperwork Americans fill out should largely be a bipartisan exercise. No one should praise spending hours on tax, health care, or housing forms. However, Americans currently labor under more than 11.6 billion hours of paperwork according to the recent tally from OIRA.

For perspective on this incomprehensible figure, it is roughly 35 hours for every man, woman, and child in the U.S. That is a work-week dedicated simply to filling out federal forms and retaining information for federal regulators.

When Congress last amended the PRA in 1996, it set a goal to reduce government-wide burdens by 10 percent in fiscal years 1996 and 1997, and at least 5 percent from 1998 through 2001. That never happened. Congress’s goal was a paperwork reduction from seven billion hours to roughly 4.6 billion hours. Instead, by 2001 the burden grew to 7.65 billion hours and to 8.2 billion hours in 2002.

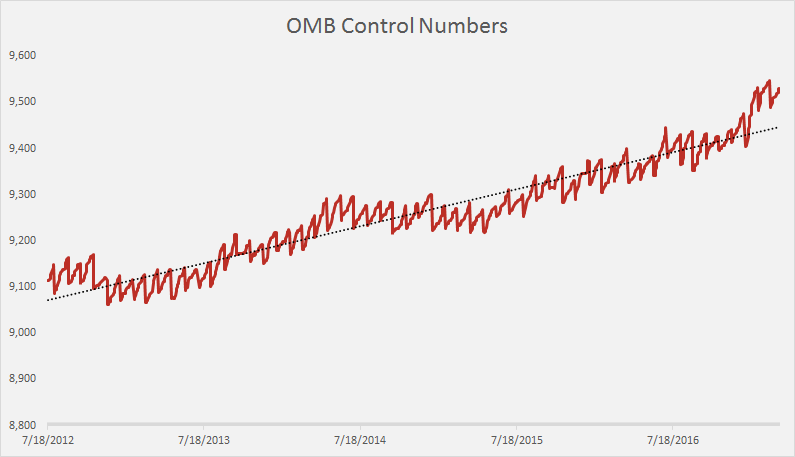

During the Obama Administration, this pace only quickened. In May of 2009, there were 8,674 OMB Control Numbers, the macro requirements that impose paperwork burdens and require OIRA approval. Today, there are more than 9,500, an increase of 9.8 percent. When AAF attempted to quantify the total number of federal forms last year, we found more than 20,000, mostly from health care and agriculture. Furthermore, since 2012, AAF has tracked daily paperwork totals, both for hours and control numbers. The growth in the graphs below is pronounced.

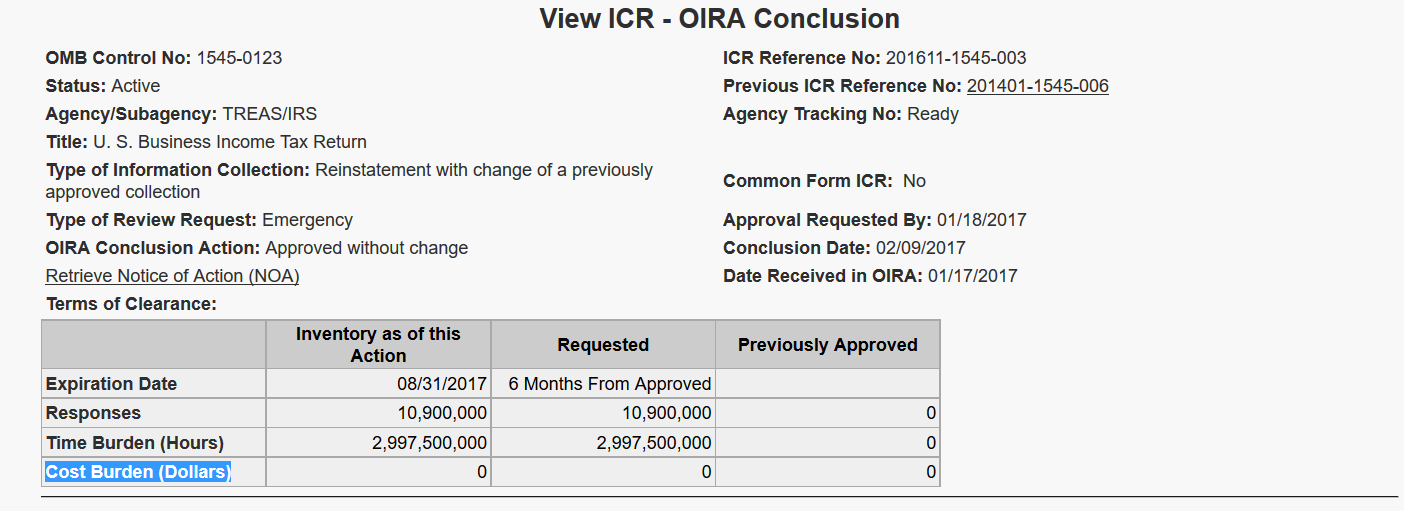

The huge dips and spikes in the hourly graph represent major tax collections expiring and renewing. For example, the U.S. Business Income Tax expired on December 31, 2016, eliminating “on paper” burdens of 2.8 billion hours. An emergency request for renewal was not sent to OIRA until January 17, 2017, with next day approval requested. It was not approved until February 9, 2017. During this month-long gap, U.S. businesses still had to pay and file taxes, but the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) did not legally have the authority to impose the requirements.

Small businesses are particularly affected by paperwork and compliance burdens. According to OIRA, there are 74 OMB control numbers that directly affect small establishments. Combined, these requirements elicit 1.3 billion responses from businesses, impose 3.3 billion hours of paperwork, and generate $5 billion in “on paper” costs. However, that $5 billion is misleading because only 31 of the 74 control numbers monetize the costs of paperwork. Using a central wage rate of $33.36 per hour (the average wage for a compliance officer) and applying it to the unmonetized hours, yields $111 billion in annual paperwork costs, not $5 billion. This is driven largely by the OIRA representation that the 2.9 billion-hour Business Income Tax does not impose monetizable costs. I will discuss this phenomenon later in the testimony.

Broadly, higher paperwork burdens can have profound impacts on smaller establishments. According to a 2013 Minneapolis Federal Reserve study, hiring two more compliance officers in small banks reduces profitability by 45 basis points and causes one-third of banks to become unprofitable. AAF research has reached similar conclusions from rising regulatory burdens.

“Compliance officer” has become a popular occupation in the nation recently. In 2013, there were 227,500; today, there are more than 257,000, an increase of 12.9 percent in just three years, outpacing overall nonfarm payroll growth of 5.7 percent.

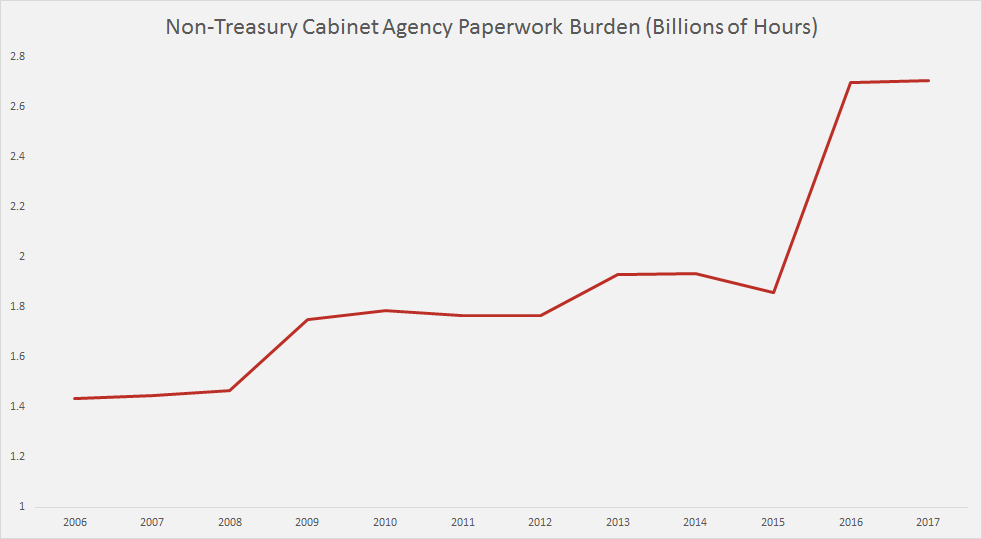

Although IRS is often seen as the main driver of paperwork in the U.S., it is not alone. The agency (Treasury broadly) does impose 8.2 billion hours, or 71 percent of the cumulative government total. Other agencies have drastically increased their regulatory burden. For instance, in fiscal year 2009, the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) imposed 494 million hours of paperwork. Today, the total stands at 1.3 billion hours, an increase of 181 percent in just one administration. Likewise, EPA’s burden has increased 22 percent since 2009 and the Commodity Futures Trading Commission has pushed its paperwork total up by 58 percent since 2013.

The totals above should not be shocking to many, considering there were fundamental changes to the nation’s energy, health care, and financial services industries during the last eight years. Although Treasury represents an out-sized burden, due mainly to tax collections, other agencies have also drastically added paperwork. The graph below depicts cabinet agency burdens with the Treasury totals excluded.

As the graph demonstrates, Treasury alone doesn’t paint the whole picture of the PRA. Non-Treasury burdens have been growing steadily during the last decade, jumping from 1.4 billion hours in 2006 to 2.7 billion hours today, an increase of nearly 93 percent. The numbers are stark, whether considering paperwork or control numbers. The bigger question is whether these figures are verifiable and how is the ultimate cost on the economy increasing because of the PRA?

Accuracy of Data and Benefit-Cost Calculations

Imagine a lowly agency that routinely imposes less than one million hours of paperwork suddenly seeking to impose 43 billion hours with one collection. There is a formal request in the Federal Register and a second notice as well. Then, the notice arrives at OIRA with no immediate correction.

That agency, the National Credit Union Administration (NCUA), originally estimated a routine “Truth in Savings Act” request would impose 43 billion hours of paperwork, require 2.6 trillion periodic statements, and each response from a credit union would take 1.58 million hours, the equivalent of 790 employees working full-time at a bank to fulfill one federal requirement. If those estimates appear unbelievable, it is because they were. The actual ongoing hourly total was just 7.1 million hours. The stark difference was not a typo, but the result of agency officials multiplying totals together when they were supposed to add them. This arithmetic error turned a routine and non-controversial requirement into potentially the largest federal collection of paperwork ever. Unfortunately, this is not an isolated example and significant mistakes are common with PRA requests.

Last April, IRS and OIRA approved a revision to the Affordable Care Act’s “Summary of Benefits and Coverage Disclosures.” The burden hours declined from 649,000 to 431,000. Strangely, the cost of compliance increased from $5 million or $7 per hour, to $1.7 trillion or $4 million per hour of compliance. There is little doubt these new health care summaries imposed some burdens, and created some benefits for consumers, but few could believe one paperwork collection imposed burdens equal to the GDP of Canada.

AAF highlighted this error last April, but it remained public on OIRA’s website until last week when the agency revised the burden down from $1.7 trillion to $9.2 million. Part of the problem was the number of responses; originally at 213 billion, it was revised down to 71 million. In its brief explanation, the agency noted costs were, “incorrectly reflected in our previous submission.” If IRS is off by roughly $1.7 trillion and NCUA erred by 43 billion hours, how many other egregious errors exist within PRA analyses?

Many former OIRA staffers have stated that PRA data is largely unreliable. Although sorting through 4,000 to 5,000 control numbers annually takes time, there is anecdotal evidence that OIRA does not consider these approvals a priority. According to one report from Rutgers University Professor Stuart Shapiro, an official noted, “I think tabulating and counting burden hours is an artificial exercise that has no use in the real world.” Another remarked, the process of burden-hour calculation was “pseudo-science.” Based on the numerical examples above, it is a mix of pseudo-science and poor calculation.

Finally, one underreported aspect of the PRA is the extent to which there is no real estimate of costs or benefits. Although benefits of transparency may be difficult to quantify and monetize at times, even a back-of-the-envelope calculation should be possible for monetizing costs. For example, last year AAF reviewed the 50 largest paperwork collections and found only seven monetized the cost of those requirements.

The listed cost of those seven collections was $44 billion, but when the remaining 43 requirements are monetized at a reasonable hourly rate, AAF found more than $61 billion in additional costs. The most egregious example is the aforementioned U.S. Business Income Tax. At 2.9 billion hours of paperwork, one would expect at least some attempt to estimate costs. Instead, the listed burden is $0.

This is a gross omission by OIRA in its PRA role because the supporting statement from IRS does list $52 billion in costs and 275 hours (nearly seven weeks) per business to file. No reasonable person would deny that there are significant compliance burdens with this collection. Yet since 1981, this collection has grown from 26 million hours to 2.9 billion (a 115-fold increase), but never once has OIRA listed a cost figure for the U.S. Business Income Tax.

Looking to other agencies, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) publicly reported a cost burden under the PRA of $41 million. Yet, the “Care Labeling Rule” and a collection for textiles imposes more than $540 million in annual burdens, more than 12 times what FTC represents publicly. AAF also found HHS’s purported PRA burden of $852 million omitted more than $5 billion in costs that were contained in supporting documents, but not reported online.

It’s striking that $60 billion in unreported costs were found in just the 50 largest collections. There are countless more requirements that have either not calculated or publicly reported the costs of imposing millions of hours of paperwork. The text of the PRA is clear that “financial resources expended” is a factor in the definition of burden. This does not appear to be the practice of many federal agencies.

Agency Violations

When business complies with federal regulation, they are held to a high legal standard. Generally, failure to comply results in fines and other penalties. For EPA, the average fine for relatively minor paperwork violations from 2009 to 2014 was $12,300, or about 14 weeks of earnings for the typical American worker. However, agencies frequently violate the PRA and there are few consequences other than a listing of violations in the administration’s annual “Information Collection Budget” (ICB).

For the past several years, the ICB has demonstrated a continual pattern of agencies flouting the PRA process, mainly the Department of Defense and HHS. In the most recent fiscal year, the Obama Administration reported 283 PRA violations, an increase of 58 violations or 25 percent more than the previous year. Generally, a violation occurs when authority to collect information or impose a recordkeeping requirement lapses.

The ICB does have a ranking system and in the most recent edition, four agencies made the “poor” list, indicating 25 or more violations. Defense (59 violations), HHS (49 violations), Homeland Security (35 violations), and IRS (30 violations) all routinely failed to comply with the PRA. In addition, OIRA classified three agencies as “needs improvement:” Agriculture (14 violations), Treasury (11 violations), and Veterans Affairs (11 violations).

Given the problems with Defense, HHS, and Homeland Security, policymakers might expect actions to correct these deficiencies. However, HHS and Defense frequently lead all agencies in the number of PRA violations. HHS led the pack in 2013, with 80 violations; Defense had 71 violations in 2012 and HHS had 57. Finally, Defense had 74 violations in 2011 and HHS was close behind with 68. Given the track record of these agencies for roughly the past six years, why aren’t they and OIRA working together to correct PRA procedure? Why are other agencies able to comply with a relatively straightforward law, yet HHS and Defense seem unable?

Although this is not a direct violation of the PRA, we have found several instances of agencies using federal money to pay respondents for information. In this EPA request, respondents could receive $50 for completing the full survey. In addition, one HHS survey of five Chinese regions offered, “a 100 Yuan (equivalent to 15 US dollars) … for completing the survey.” Finally, another HHS collection offered web participants $10 and focus groups $30 per person for their participation. This might increase response rates for agencies, but it could result in a non-representative sample, and of course, it does spend taxpayer money.

Finally, there is the ministerial matter of simply publishing the ICB. Like the Unified Agenda and OIRA Reports to Congress, the ICB has somehow morphed into a political football. It wasn’t until October of 2014 when the Obama Administration released its 2013 and 2014 ICB together, a gap of 20 months from the 2012 ICB. To compound the delays, the Obama Administration waited more than two years to issue the next ICB. Like the Unified Agenda, a basic report outlining paperwork at the federal level should not be a political matter and reporting should be annual, given the ICB reflects paperwork within a given fiscal year. In the future, OIRA should work to publish the ICB in a timely manner every year.

Reform Options

One primary duty of the Administrator of OIRA is to, “minimize the Federal information collection burden, with particular emphasis on those individuals and entities most adversely affected.” It’s clear, from a wealth of academic and other peer-reviewed studies, that small businesses are most adversely affected by large paperwork impositions. What evidence is there that the federal government is actively attempting to reduce paperwork on small entities?

For instance, during the Obama Administration, there were 17 PRA actions that reduced paperwork by more than one million hours. However, just one of these 17 deregulatory actions directly affected small businesses and a Regulatory Flexibility Act analysis was only performed for four of them. Of the 17 largest reductions under the PRA during the last eight years, just one directly benefited the smallest businesses. Why, when the impacts of hiring additional compliance officers are most pronounced for the smallest institutions?

AAF has studied this phenomenon in the past. We found that a ten percent increase in cumulative regulatory costs results in a five to six percent decrease in the number of small business establishments (fewer than 20 employees). On the other hand, the largest businesses (more than 500 employees) actually saw growth in the number of establishments, by two to three percent, in the face of rising regulatory burdens. Thus, it appears that high regulatory burdens impact small businesses the most and a disproportionate share of the deregulatory actions do not benefit these businesses directly.

Monetize and Report Costs

With regard to the PRA, as discussed above, agencies should attempt at least a back-of-the-envelope monetization of hourly burdens. The PRA speaks directly to “financial resources expended,” but agencies either decline to monetize notable hourly burdens or OIRA, for some reason, fails to report these tabulations online.

As an example, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) currently has 50 active control numbers. Of those, only 14 provide cost estimates for hourly burdens online. One of its largest collections, Regulation V, imposes 4.1 million hours of paperwork, but OIRA lists $0 in burdens. Yet, the supporting statement declares $110 million in associated labor costs, more than CFPB’s total listed burden of $42 million. Likewise, its implementation of a Dodd-Frank collection imposed 387,500 hours of paperwork, but in the supporting statement, CFPB bluntly declares, “There will be no annualized capital or start-up costs for the respondents to collect and submit this information.” Does anyone believe there are no costs to comply with more than 380,000 hours of paperwork? Unfortunately, the examples above are only a fraction of the discrepancies and omissions replete with PRA compliance.

Setting Reduction Targets

To address the rising volume of paperwork, Congress could set hard caps on growth and even targeted reductions, as it did with the 1996 amendments to the PRA. Unfortunately, agencies never met those reduction targets and paperwork increased. Legislators can learn from those past mistakes and devise a way to make reductions enforceable. This will require coordination with OIRA and perhaps even some penalties or incentives for agencies during compliance. Reforms could address the cumulative amount of paperwork and the number of control numbers. Although a ten percent reduction might sound trivial, that would equal 1.1 billion hours or $38.6 billion in annual savings (assuming $33.26 per hour).

Online Reporting

There is also the issue of general modernization in reporting under the PRA. When EPA moved its National Pollution Discharge Elimination System online, the agency claimed $156 million in total savings to the industry over ten years, $23 million annually, and nearly 200,000 fewer paperwork burden hours. Unfortunately, submitting forms online is still not possible for many agencies. For example, there are 5,257 control numbers that contain forms in the federal government; only 3,284 may be submitted electronically. In other words, there are nearly 2,000 forms that cannot be submitted online. Congress, federal agencies, and OIRA could work to drastically lower that number to provide cost savings to government, individuals, and businesses.

Increase Public Participation

The paperwork burdens under the PRA are incredibly top-heavy. The ten largest collections impose 70 percent of all paperwork hours. However, the largest, most impactful requirements, are treated the same as the smallest, most routine collections.

Congress and the administration could examine opportunities to place more scrutiny on the largest paperwork requirements and deemphasize routine collections. This could take the form of proposed and final rule status for significant measures, as opposed to treating them as one of hundreds of weekly notices in the Federal Register. Historically, even major collections receive few substantive comments. If the goal of PRA reform is to increase public participation and accuracy, perhaps more scrutiny of major collections is one method to explore.

Conclusion

The PRA has existed for more than a generation, but flaws remain in a law ostensibly designed to “reduce” paperwork. That goal has clearly failed, as the PRA has turned OIRA into a manager of paperwork, one where “pseudo-science” reigns and little hard data exist. Reforming the PRA to increase public participation, eliminate redundant forms, and strengthen benefit-cost analysis, should be a bipartisan exercise. For the next generation of the PRA, government should strive to produce better data while imposing lower costs on respondents and the federal government.

Thank you. I look forward to answering your questions.