Weekly Checkup

July 19, 2019

Requiem for the Cadillac Tax

Earlier this week, opponents and supporters of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) came together on the House floor in a rare kumbaya moment to repeal the law’s so-called “Cadillac” tax. There are both policy and budget implications from this change.

Recall that the Cadillac tax is—or rather was—a 40 percent excise tax on what were deemed excessively generous employer-sponsored health insurance (ESI) plans. To fully understand the history, one needs to return to the 2008 presidential campaign, when then-Senator and presidential candidate John McCain called for equalizing the tax treatment of health insurance. Individuals buying insurance on their own must do so using after-tax dollars (this will change somewhat in 2020 in light of the Trump Administration’s recent rule on Health Reimbursement Arrangements). Employees with ESI, however, pay with pre-tax dollars. Economists and health policy experts have long decried the disparate treatment. The McCain proposal would have eliminated the tax exclusion for ESI and instead provided every American with a refundable tax credit for the purchase of health insurance. Then-Senator and presidential candidate Barack Obama successfully framed this as a first-ever tax on employee health benefits. But this political win created a policy problem.

Once President Obama started developing his health plan, it became obvious that large sources of revenue were needed to pay for it. The tax exclusion was an obvious source of revenue, but having campaigned against that idea, Obama needed another option. Thus, the Cadillac tax was born as a convoluted, inefficient, backdoor way of getting at the same revenue stream. The Cadillac tax immediately became a political headache for Democrats, due to its impact on union members who for decades had negotiated larger and larger untaxed benefit packages. In fact, the Cadillac tax has been roundly objected to by virtually everyone outside of health policy wonks and economists—though even they would prefer a more direct approach. At this point, the tax seemed unlikely ever to take effect. As such, it probably makes sense to clear it off the books. But I’d like to draw your attention to another facet of this episode.

The Weekly Checkup has previously considered the utility of legislative cost-estimates. These estimates provide a valuable source of information when evaluating policy ideas, but they are ultimately carefully researched guesses and shouldn’t be determinative. Often, a score from the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) showing a proposal will increase spending can send a good idea to the discard pile. On the other hand, a score showing federal savings is touted as reason in-and-of itself to enact the policy.

During the ACA debate, the talking point that the law would be completely paid for was crucial to Democrats’ ability to build public support and enact the legislation. Not only are these scores inherently inaccurate, but those doing the scoring are bound by law to consider only what is written in the legislation (in other words, CBO is prohibited from considering the likelihood that future policymakers will renege on some of the provisions—even if there is a high likelihood they will do so). CBO scored the Cadillac tax as generating $149 billion in revenue between 2010-2019 in the Senate-passed version of the ACA, accounting for more than 100 percent of the bill’s total expected savings. By the time the legislation passed the House and went to the president to sign, the Cadillac tax had been delayed to 2018 and was only expected to generate $32 billion in revenue.

Of course, we now know even that amount would never materialize, and since Republicans generally don’t believe that tax cuts need to be paid for, and Democrats generally are disinclined to pay for anything, the Cadillac tax was never more than a budgetary gimmick to ease passage. The Cadillac tax is yet another reminder that scoring estimates are useful tools, but they are also imperfect predictors of outcomes and should not trump careful policy analysis and decisions about tradeoffs by legislators.

Chart Review

Ryan Haygood, Health Care Policy Intern

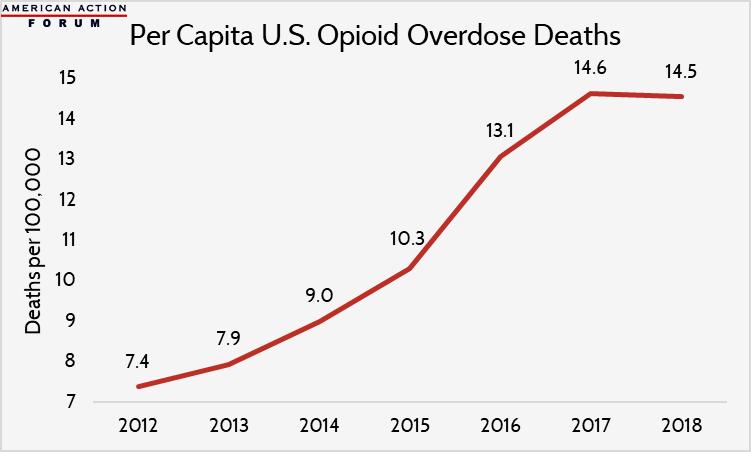

Although total U.S. opioid overdose deaths remain higher than ever, at 47,600 deaths annually, preliminary data indicate that their rapid growth has stopped and the death rate (shown below) has declined for the first time—at least for now. Looking beneath the headline estimate, this slowdown owes largely to fewer prescription painkiller deaths, which dropped from 14,500 to 12,800. Ohio and Pennsylvania, two heavily impacted Rust Belt states, witnessed among the sharpest declines in overdose deaths, while Maryland and Vermont saw continued marked growth in death rates. The Trump Administration has allocated $3.3 billion to combat the opioid epidemic through state grant programs expanding access to medication-assisted treatment options, which may also be a factor in the slowdown.

Data through 2017 is from the Kaiser Family Foundation; 2018 data, from the New York Times, is preliminary and subject to revision.

From Team Health

Event: Arbitration and Drug Pricing

Please join AAF on July 23 for a panel discussion over lunch examining the potential and pitfalls of current proposals to employ arbitration in drug pricing. Register here.

How Congress is Attempting to Lower Drug Costs

Deputy Director of Health Care Policy Tara O’Neill Hayes outlines the various proposals for lowering drug prices considered thus far and highlights their fundamental aim.

Worth a Look

Kaiser Health News: A ‘No-Brainer’? Calls Grow For Medicare To Cover Anti-Rejection Drugs After Kidney Transplant

STAT News: Do Elon Musk’s brain-decoding implants have potential? Experts say they just might