Weekly Checkup

April 17, 2020

The Challenge of the Newly Uninsured

Over the past four weeks, 22 million Americans have filed for unemployment, with real unemployment estimated as high as 18 percent and likely to climb higher before things get better. The spiraling job loss is significant for myriad reasons, but one ramification policymakers will feel increasing pressure to address is the impact on health insurance coverage.

More Americans get their insurance through their employer than from any other source. In 2018, 157.3 million Americans received health insurance through their employer as part of their compensation. That’s 49 percent of the population. With unemployment growing at staggering rates, many Americans will be losing their health insurance along with their paycheck. To be sure, not everyone who loses their job as a result of the ongoing national shutdown will lose their health insurance; job loss has been heavier in the service industry where fewer employees receive employer-sponsored insurance (ESI). But sustained job loss on the scale we’ve seen so far will increasingly impact workers who do receive ESI.

Activists on the left will put tremendous pressure on policymakers to take advantage of the pandemic’s disruption and pursue various priorities such as Medicare for All or a public health insurance option. But this response would be foolish. As I wrote last week, a crisis is not the time to enact sweeping policy changes. Rather, the focus should be on the immediate needs, and one of the most immediate challenges is what to do about the newly uninsured.

In this vein, there have been increasing calls for the Trump Administration to reopen enrollment through the Affordable Care Act’s (ACA) exchanges in response to the pandemic and related job loss. President Trump has rejected these calls. The fight over a special enrollment period (SEP) seems to me to be more style than substance. The primary justification for a SEP is that people are losing their insurance along with their jobs. Job loss, however, is a qualifying life event already, meaning that those who lose their insurance because they lost their job as a result of the pandemic will be eligible to sign up for insurance through the ACA’s Marketplaces.

Another policy initiative gaining attention is the idea of providing federal subsidies for COBRA—a transitional insurance program dating back to 1985 that allows employees to continue with their existing ESI plan for between 18 and 36 months in most cases, provided they pay both the employee and employer shares of the premium. COBRA provides continuity, but it also can be prohibitively expensive. House Democrats are pushing for the federal government to pay the entire cost of COBRA premiums for an as-yet undetermined duration. Health insurers would also like to see consumers get help with COBRA premiums at least temporarily.

Conservatives are rightly hesitant to embrace yet another expansion of the federal role in financing health care. One can easily imagine COBRA subsidies being extended again and again in coming years. At the same time, there is perhaps value in keeping people in the insurance plan and provider network they’re already familiar with. Amid all the other disruptions buffeting the country, having 20 million (or 30 million or even 40 million) newly unemployed Americans trying to acclimate to a new insurance plan and provider network in the middle of a public health crisis could be counterproductive. One possibility to preserve continuity would be to allow the newly unemployed to apply the ACA premium subsidy they could receive on the exchange to their COBRA plan, and sunset the subsidy after the public health emergency has ended.

Regardless of whether COBRA subsidies are ultimately the right approach, policymakers will need to grapple with the implications of tens of millions of Americans losing their ESI. Policymakers would be wise to focus on the problem at hand, rather than pursuing broad, system-wide reforms in a time of crisis. And it would make sense to limit disruption to existing insurance arrangements during the pandemic to the degree possible.

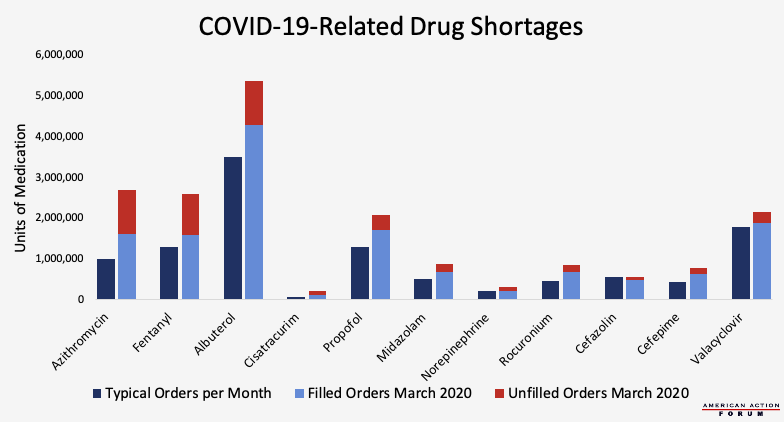

Chart Review: Drug Shortages Related to COVID-19

Margaret Barnhorst, Health Care Policy Intern

With the massive influx of COVID-19 patients, many hospitals are struggling to obtain the medications they need to treat patients on ventilators. According to new research from medical supplier Premier Inc., shortages are already evident for antivirals (Valacyclovir), antibiotics (Azithromycin, Cefazolin, Cefepime), vasopressors (Norepinephrine), neuromuscular blockers (Rocuronium, Cisatracurium), bronchodilators (Albuterol), and sedatives (Propofol, Midazolam, Fentanyl)—a combination of medicines that help treat patients on mechanical ventilators, keep airways open, control lung functions, reduce fevers, and manage pain. The demand for these critical drugs increased dramatically last month, with orders for antibiotics nearly tripling. Of note, the demand for Azithromycin increased 170 percent in March, and the demand for Cisatracurium increased 253 percent. Demand for Albuterol, a common medication in asthma inhalers, also rose significantly in March because of its use in easing respiratory distress in COVID-19 patients, therefore limiting the supply for asthmatic patients. As a result of this increased demand, the rate at which prescriptions are filled has decreased significantly, as seen by the number of unfilled orders in March. Before COVID-19 outbreaks, the average fill rate for ventilator-associated drugs was 95 percent, but it now ranges from only 51 percent (Cisatracurium) to 87 percent (Valacyclovir). In attempts to make these medications more accessible, pharmaceutical companies such as Pfizer and Teva Pharmaceuticals are adjusting production schedules to prioritize certain drugs, and the Drug Enforcement Administration temporarily increased production quotas for sedative drugs and medications necessary for patients on ventilators.

Data obtained from Premier Inc. COVID-19 Pharmaceutical Supply Chain Vulnerabilities Survey from March 31, 2020

From Team Health

Combatting COVID-19 After the Peak – Health Care Data Analyst Andrew Strohman

A national syndromic surveillance system could help society move toward normalcy before a vaccine comes online, but such a system also raises privacy concerns.

UPDATE: The Many Competing Proposals to Reform Medicare Part D – Director of Human Welfare Policy Tara O’Neill Hayes

Over the past year, Congress has put forward several proposals to lower prescription drug costs, each of which seeks to put downward pressure on prices by realigning incentives.

Analysis of the Competing Proposals to Reform Medicare Part D – Tara O’Neill Hayes

While the reform proposals are conceptually similar, the differences in the details result in significantly different impacts for the various stakeholders.

COVID-19: Impact and Response

All of AAF’s analysis on the pandemic and the federal government’s response can be found on this organized dashboard.

Worth a Look

FierceHealthcare: Healthcare leaders urge CMS, ONC to incentivize telehealth adoption as part of the ‘new normal’

Washington Post: Nurses, doctors take extreme precautions to avoid infecting family members