Weekly Checkup

September 4, 2020

What Can the States Teach Congress About Surprise Medical Bills?

At the start of 2020, two issues in health care policy—drug prices and surprise medical bills—looked primed for action. But then the COVID-19 pandemic hit and swamped the best laid plans of mice and congressional leaders. More recently we’ve seen the Trump Administration give up on congressional action on drug prices and move forward with a slew of questionable executive orders and rulemakings. But on the matter of surprise medical bills, Congress is quietly still working away. While Congress continues to seek consensus, however, states have been taking action with increasing frequency, and with increasing similarity.

A surprise medical bill occurs when an insured patient receives either non-emergency or emergency care at an in-network facility, but one or more of the providers who treat the patient are not in the patient’s insurance network. Alternatively, a surprise medical bill can occur when an insured patient receives emergency care at an out-of-network facility. In these instances, patients can be billed for the difference between what a provider charged and what the insurer actually paid. Some 30 states have acted to protect patients from these unexpected charges, with several currently debating proposals. But states are prohibited from regulating large, self-insured health plans common to large employers under the Employee Retirement Income Security Act of 1974. As a result, in the absence of federal legislation, even in states that have enacted policies to prevent surprise medical bills, many patients are still unprotected.

As Congress seeks to negotiate a solution to surprise medical bills, it’s worth looking at how states have approached the challenge. Of the 30 states that have acted to protect patients, nine have stopped there, leaving it to providers and payers to fight out payment among themselves. Four states have opted to establish guidelines for insurer payments to out-of-network providers, in effect rate setting. Alternatively, 10 states have enacted some form of arbitration or independent dispute resolution process (IDRP) to resolve payment disputes between providers and insurers over out-of-network (OON) care. Finally, seven states have established an IDRP and combined it with a rate-setting component for initial payments prior to entering dispute resolution.

I wrote about these state approaches in a new paper published this week, and what emerges from a careful examination is that despite nuanced differences, there is a substantial amount of consensus among the various state approaches: Three-fifths of states have undertaken measures to protect patients from surprise medical bills (and there is consensus that patients are being well served in those states with comprehensive approaches); over two-thirds of these states have sought to mediate payment disputes between providers and insurers over OON services; and more than half of the states that have regulated surprise medical bills have included some type of independent dispute resolution. Further, the vast majority of states that enacted these laws within the last year—including Georgia, Virginia, Washington, and Texas— have gone this route and incorporated IDRPs.

Perhaps of particular interest to federal lawmakers, these recent approaches have been taken in red states, purple states, and blue states. These laws have been signed by Republican governors in Texas and Georgia and by Democratic governors in Washington and Virginia. As federal policymakers continue to work on a national surprise billing solution, they have many factors to consider, but a growing consensus in approach at the state level is certainly worth their close examination.

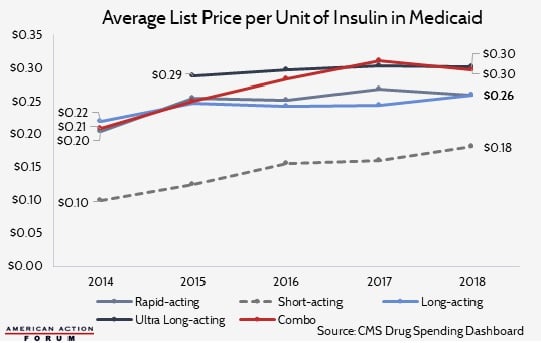

Chart Review: The Price of Insulin in Medicaid

Josee Farmer, Former Health Care Policy Intern

Overall Medicaid spending on insulin increased an average of 24.2 percent per year between 2014 and 2018. During this period, Medicaid enrollment increased significantly due to Medicaid expansion under the Affordable Care Act, a factor that certainly lead to increased insulin spending, but rising insulin list prices, depicted by the chart below, contributed as well. In 2017, however, average list prices in the Medicaid market leveled off, with the price for some insulin types even decreasing. The change in the trend correlates with recent declines in net prices – the price that includes rebates and discounts. This trend change could also be the result of greater variation in the market or of specific products losing their appeal as new products become available to patients.

Data obtained from CMS Medicaid Drug Spending Dashboard

Worth a Look

New York Times: 2 College Students Dreamed Up an A.L.S. Treatment. The Results Are In.

Axios: California could become first state to produce generic drugs