Weekly Checkup

July 12, 2019

Where Does It Go From Here? Drug Pricing Policy After the Rebate Rule Reversal

Late Wednesday, news broke that the Trump Administration was withdrawing a controversial proposed rule that would have altered how drugs are paid for in the Medicare Part D program. There is much to say about the potential merits and challenges of the proposed rebate rule, but the administration’s decision to abandon it is perhaps more important for what it signals about where the drug pricing debate is headed.

While the rebate rule would have been a significant change in Medicare policy with a host of implications for all stakeholders—manufacturers, insurers, the federal government, pharmacy benefit managers, and beneficiaries—it was still limited in scope. The rule would have likely increased premiums moderately for all Part D plans, while providing steep discounts to some patients who are prescribed especially high cost medications. The proposal was also projected to increase federal spending—though how much weight to give to those estimates is unclear, and something AAF has contemplated here, here, and here. The bottom line, however, is that the policy itself made sense in that it would have spread risk more equitably across the pool of beneficiaries.

Yet—and here’s the rub—any effects were largely limited to the Part D program, and it probably wouldn’t have had a notable impact on drug list prices.

President Trump has been clear that he is laser focused on the issue of drug list prices. In October 2017 the president said, “Prescription drug prices are out of control. The drug prices have gone through the roof. The drug companies, frankly, are getting away with murder.” In his 2018 State of the Union address, Trump pledged to make “fixing the injustice of high drug prices one of our top priorities for the year. And prices will come down substantially. Watch.” While it might have been good policy, the rebate rule wouldn’t have achieved the president’s goal of bringing down list prices. Further, the rebate rule faced opposition from Congress as well as from inside the White House, due to the political implications of increasing seniors’ Part D premiums.

The pressure to do something (really, anything) to bring down drug prices isn’t going away. With the rebate rule off the table, there will be renewed focus on finalizing the even more controversial—and misguided—International Price Index proposal, which would set prices for Medicare Part B drugs at a rate based on an index of what other countries pay for those drugs. Further, President Trump’s commitment to lower drug prices means that Republicans, and especially those in the White House, will feel an increasing need to reach a deal with House Democrats on legislation reducing drug prices.

All these policy roads seem to be leading toward expanded federal government intervention in the drug marketplace, a policy path Republicans have historically been loath to tread. But across the health care space, both Democrats and now Republicans seem eager to involve further the government in matters that have traditionally been left to the private sector: see Senate and House legislative proposals (detailed by AAF’s Jonathan Keisling here) aimed at dictating how hospitals, insurers, and physicians should handle “surprise” medical bills.

Health care in America isn’t by any means a “free” market. Even before the Affordable Care Act, there were simply too many federal-policy shackles on the various stakeholders to pretend it was an unfettered marketplace. And arguably, health care shouldn’t be left entirely to unrestricted market forces. At the same time, the federal government has historically approached market intervention, even in health care, from the perspective that markets work and that government direction of the economy should be limited. It’s exactly this philosophy that led to a successful Part D program.

Do we still believe markets generally work, and that market forces lead to better outcomes? The fact that the health care market is not a completely free market does not mean we should actively erode market forces, but unfortunately, that seems to be where policymakers are heading.

Chart Review

Ryan Haygood, Health Care Policy Intern

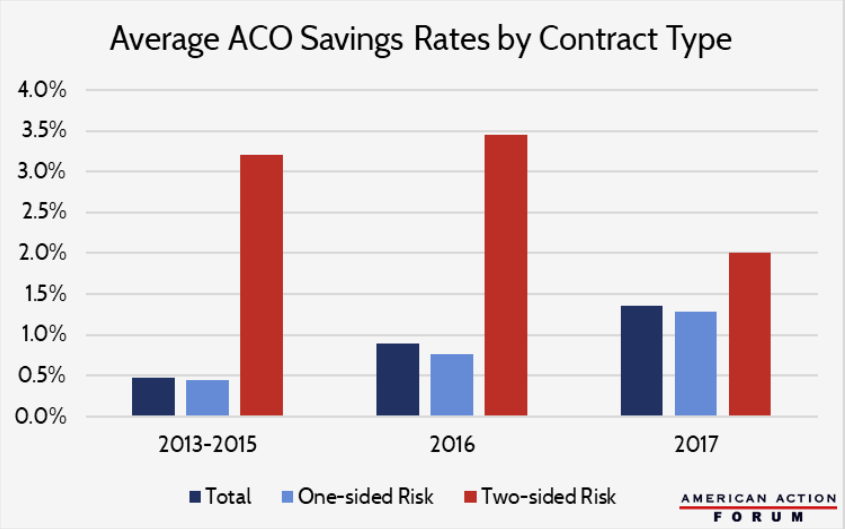

As part of the ACA’s move from volume- to value-based payments, Medicare formed its first shared-savings contracts in 2012 with dozens of Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs), groups of providers that voluntarily coordinate care in an effort to cut costs without compromising quality. Under the program, if an ACO generates cost-savings while adhering to certain quality standards, Medicare reimburses it a share of the savings. That share is 50 percent for one-sided, “upside-only” contracts, which hold the ACO harmless if its costs grow, and 60 or 75 percent of savings for two-sided contracts, which penalize ACOs for cost-growth. By imposing real risks on these two-sided ACOs, Medicare hopes to incentivize further cost-savings, and it intends to phase out upside-only contracts and move these into the expanded-risk model over time. Indeed, two-sided contracts have historically outperformed the one-sided model, but uptake has been slow — 82 percent of 2018 ACOs are still upside-only. Program-wide cost savings remain meager, and it’s unclear if expanding two-sided models will move the needle, since ACOs that have opted for downside risk may have done so because they expected high savings to begin with.

From Team Health

Assessing the Legislative Responses to Surprise Billing and Other Transparency Issues

Health Care Policy Analyst Jonathan Keisling examines the mechanics and potential impact of House and Senate efforts to curb the prevalence of surprise medical bills.

The Inconsistent Treatment of Biosimilars in Medicare and Medicaid

Deputy Director of Health Care Policy Tara O’Neill Hayes digs into the treatment of both biosimilars and generics to explain when, and why, federal policy treats them differently.

Daily Dish: Advancing American Kidney Health

AAF President Douglas Holtz-Eakin explains the reasoning behind President Trump’s executive order focusing on end-stage renal disease.

Worth a Look

Reuters: Study finds possible link between sugary drinks and cancer

STAT News: Canada case highlights possible long-term risks of experimental stem cell therapy