Research

October 3, 2019

Projecting FY 2019 Regulatory Budget Results

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

- The end of fiscal year (FY) 2019 on September 30 wrapped up the latest year of the Trump Administration’s regulatory budget, which established a goal of $17.9 billion in total savings across all executive agencies.

- This analysis estimates the administration missed its target but still achieved net savings of $8.6 billion for FY 2019.

- At the agency level, the Department of Health and Human Services achieved the most net savings while the Department of the Treasury added the most net costs.

- Some rules that were not clearly regulatory or deregulatory could have implications for the Trump Administration’s final accounting later this year.

INTRODUCTION

The end of FY 2019 completes the latest year of the Trump Administration’s regulatory budget, in which the administration established a net-savings target for the economic impact of its regulatory and deregulatory actions. The American Action Forum (AAF) has tracked the rules subject to the regulatory budget for FY 2019, and this analysis presents an estimate of how the Trump Administration fared in achieving its regulatory budget goals. The administration is expected to release its final accounting of the regulatory budget in the coming weeks.

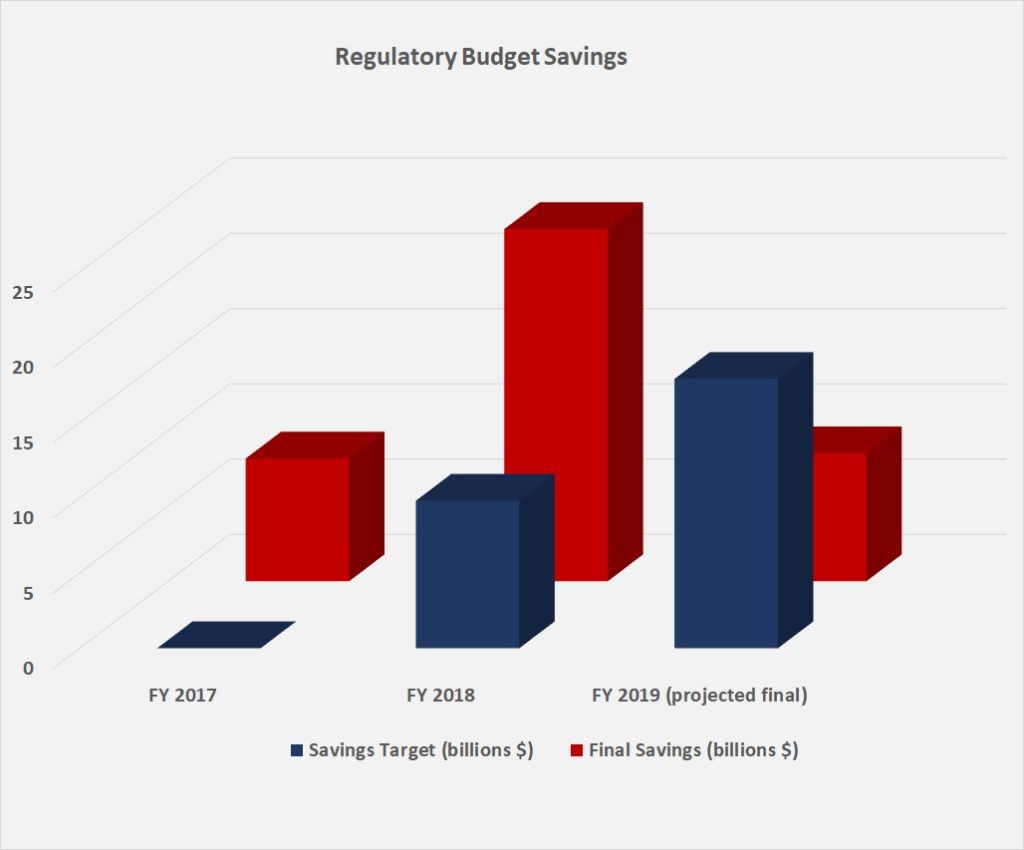

Whereas in previous fiscal years the Trump Administration cruised past its goal, achieving $9.8 billion in savings in FY 2017 (against a savings $0 net target) and $23.4 billion (against an $8.1 billion net target) in FY 2018, FY 2019 proved trickier. AAF estimates the administration fell short of its ambitious savings target but still managed to end the fiscal year with a net deregulatory tally, i.e. with savings outweighing costs. Some rules, however, were not clearly regulatory or deregulatory, and these rules could affect the Trump Administration’s final accounting later this year.

HOW THE REGULATORY BUDGET WORKS

Executive Order (EO) 13,771, one of the first executive orders issued by President Trump in January 2017, established the principles for the regulatory budget. That order called for no new net costs through September 2017, with the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) setting a budget for FY 2018 and subsequent years. OMB established an administration-wide target for FY 2019 of $17.9 billion in net-present-value savings from new rules, with each covered agency receiving a prescribed target.

Not all rules count under EO 13,771 – in fact, most do not. The executive order, and its subsequent guidance, define an “EO 13,771 regulatory action” as one that has an annual effect on the economy of $100 million or more; creates a serious inconsistency or otherwise interferes with an action taken or planned by another agency; materially alters the budgetary impact of entitlements, grants, user fees, or loan programs; or raises novel legal or policy issues and is finalized with costs greater than zero. An EO 13,771 deregulatory action, however, is merely an action finalized with costs less than zero. To provide context on how this definition limits the universe of covered rules, AAF identified 287 final rules from October 1, 2018, through September 30, 2019, with quantified cost or savings estimates. AAF found 106 of these rules to be covered by EO 13,771, and just 35 are EO 13,771 regulatory actions.

To hold agencies accountable to meet their targets, EO 13,771 requires that any covered agency failing to meet its target must develop a written plan explaining how it plans to make up for it in the future. EO 13,771 does not impose any penalty beyond that, however.

CUMULATIVE PROJECTION AND AGENCY-BY-AGENCY ANALYSIS

AAF tracked final rules published in the Federal Register with estimated costs or savings and identified as either regulatory or deregulatory for the purposes of EO 13,771. The cumulative net present value of the 106 such actions was $8.6 billion in savings, about $9.3 billion short of the Trump Administration’s target of $17.9 billion. For the third straight time – including the partial FY 2017 – the administration will deliver net savings as a result of its regulatory reform efforts. The chart below shows the three years’ final savings compared to its respective savings target.

Of course, the cumulative projection is only part of the story. Each agency was given its own FY 2019 target, which together added up to the $17.9 billion cumulative target. Those targets, along with AAF’s tracking results, are shown in the table below.

| Agency | FY 2019 Budget ($millions) | FY 2019 Projected ($millions) | Difference ($millions) | EO 13,771 Deregulatory Actions | EO 13,771 Regulatory Actions |

| HHS | -8,995.60 | -9,251.64 | 256.04 | 14 | 13 |

| Labor | -723.20 | -7,589.50 | 6,866.30 | 7 | 2 |

| Transportation | -1,869.50 | -2,248.10 | 378.60 | 13 | 2 |

| Interior | -793.60 | -1,543.09 | 749.49 | 1 | 0 |

| Agriculture | -981.30 | -422.50 | -558.80 | 7 | 0 |

| Homeland Security | 0.00 | -271.14 | 271.14 | 3 | 4 |

| Energy | 0.00 | -233.61 | 233.61 | 2 | 0 |

| Education | -3,173.00 | -216.10 | -2,956.90 | 2 | 0 |

| Justice | 0.00 | -46.47 | 46.47 | 1 | 1 |

| FAR | 0.00 | -31.76 | 31.76 | 4 | 1 |

| HUD | -490.70 | -30.94 | -459.76 | 2 | 0 |

| USAID | 0.00 | -11.36 | 11.36 | 1 | 0 |

| Defense | 0.00 | -0.95 | 0.95 | 2 | 0 |

| Commerce | -51.20 | 0.00 | -51.20 | 0 | 0 |

| EEOC | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0 | 0 |

| GSA | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0 | 0 |

| NASA | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0 | 0 |

| OMB | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0 | 0 |

| OPM | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0 | 0 |

| SBA | -8.80 | 0.00 | -8.80 | 0 | 0 |

| SSA | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0 | 0 |

| State | 0.00 | 49.81 | -49.81 | 0 | 1 |

| EPA | -817.80 | 1,353.99 | -2,171.79 | 8 | 6 |

| Veterans Affairs | 0.00 | 2,260.15 | -2,260.15 | 3 | 3 |

| Treasury | 0.00 | 9,653.16 | -9,653.16 | 1 | 2 |

| Total | -17,904.70 | -8,580.05 | -9,324.65 | 71 | 35 |

Overall, 16 of the 25 agencies given a regulatory budget by OMB met or exceeded their savings target. Nine agencies failed to meet their target, although three of those (the Departments of Agriculture, Education, and Housing and Urban Development) still achieved projected net savings over the course of the fiscal year. Two of the nine, the Department of Commerce and the Small Business Administration, imposed no costs.

The agency that delivered the largest savings total for the second consecutive year was the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), with $9.3 billion in savings for FY 2019. It was followed by the Department of Labor (DOL) ($7.6 billion), the Department of Transportation (DOT) ($2.2 billion), and the Department of the Interior (DOI) ($1.5 billion) as the only agencies to achieve more than $1 billion in savings.

The top three agencies by the amount they exceeded their savings target were DOL ($6.8 billion), DOI ($750 million), and DOT ($379 million).

On the opposite end of the ledger, the Department of the Treasury imposed the most net costs of any agency, with more than $9.6 billion. It also is the agency that missed its budget target by the largest amount. In fairness, nearly all of its costs came from paperwork associated with a rule implementing the Qualified Business Income Deduction – a rule required under the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017. It is unclear why the rule was not incorporated into its regulatory budget since it was expected to be issued during FY 2019.

The two other agencies to top $1 billion in net costs for FY 2019 were the Department of Veterans Affairs ($2.2 billion) and the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) ($1.4 billion). EPA’s inclusion on this list is a surprise, given it had the fifth-largest savings target at $817 million. A big part of its failure may be traced to the change in expected savings from its Affordable Clean Energy (ACE) rule (this change is explained here). Still, the change clearly was not a major surprise to the agency or OMB, since its savings target of under $1 billion was miniscule compared with the $58 billion in estimated savings initially expected from the ACE rule.

Though it achieved net savings for FY 2019, the Department of Education ended up with the biggest miss of its regulatory budget of any agency outside of Treasury, missing its savings target by $2.9 billion.

Readers of AAF’s Week in Regulation series will recall that as FY 2019 approached its conclusion, the administration seemed destined to miss its $17.9 billion savings target by $20 billion or more. The reason for the turnaround stems from agencies publishing two huge savings rules in the waning days of the fiscal year. On September 27, DOL published its revision to the Overtime rule, which brought $7.6 billion in total savings, and on the final day of the fiscal year, HHS published a Medicare and Medicaid rule that saved more than $9 billion.

QUESTIONABLE CASES

As the Trump Administration concludes its second full fiscal year of EO 13,771 implementation, it is worth noting that regulatory budgeting is still a relatively novel policy exercise in the United States. As such, the administration is still developing the exact parameters for calculating the impact of regulations. For instance, the FY 2018 budget goals focused primarily on annualized costs or savings, while this year’s involved present-value figures. The preceding analysis focuses upon those rulemakings that: A) had some sort of quantified costs or savings and B) had a clear designation as either “regulatory” or “deregulatory.” There were, however, a handful of notable rules that could affect the FY 2019 regulatory budget but for which the designation was not so clear. The following rules present curious case studies in how agencies can consider costs versus savings.

The most notable of such rules is one out of the Department of Agriculture (USDA) regarding a “National Bioengineered Food Disclosure Standard.” The rule establishes the requirements that “food manufacturers, importers, and other entities that label foods for retail sale” must meet in disclosing the bioengineering status of their products. USDA estimates that this rule could bring annual costs of up to $391 million, or roughly $5.6 billion in present value (when discounted at 7 percent in perpetuity). As USDA further notes, however, since this national standard could preempt a more rigorous state-level standard out of Vermont, it could instead represent $77 million in annual net savings (or $1.1 billion in present value).

This divergence leaves one wondering where it fits into the EO 13,771 calculations. The rule provides no clear EO 13,771 designation, and it is simply categorized as “Other” in the Unified Agenda. The determination of its relative status is important here as the dueling baselines generate a budgetary difference of $6.7 billion. Including it as regulatory reduces the administration’s savings total down to only $3 billion in net savings for FY 2019, while including it as deregulatory pushes the ledger to $9.7 billion in total net savings. In the analysis above, this rule is omitted from the totals due to its lack of designation. The issue of disparate baselines in rules preempting state-level standards will continue to be relevant as such notable measures as the Safer Affordable Fuel-Efficient Vehicles Rule continue to wind their way through the regulatory and legal process.

While the case of the bioengineering rule represents a particularly massive gap, there are other, relatively less significant rules that still present interesting questions regarding EO 13,771 nomenclature. The first such rule is a joint rulemaking involving HHS, DOL, and Treasury that establishes a new regulatory framework for “health reimbursement arrangements.” The agencies are seeking to establish the ability of employees and employers to use such arrangements, and thus, the agencies consider the rule to be deregulatory. In establishing a new set of administrative requirements, however, the rule still brings $80.6 million in net costs on a quantified basis.

The second instance this past year of a mismatch between costs and the rule’s designation has been a rule regarding the limitations on H-2B visas for FY 2019. The agencies involved (DHS and DOL) have deemed this rule to be a deregulatory action even though it brings an additional $11.9 million in costs over the course of the year. How does this happen? The rule increases the cap on potential visas, thus opening further employment opportunities for the applicants (a “deregulatory” move), but more applicants completing the administrative process necessarily represents an increase in the aggregate paperwork burden. Rulemakings such as these will continue to present themselves. Whether their place in a regulatory budget scheme becomes clearer is an open question.

CONCLUSION

The Trump Administration failed to achieve its cumulative regulatory budget goal of $17.9 billion in net present value savings, based on AAF tracking. For the third straight year, however, the administration did achieve net savings – a notable accomplishment. The majority of agencies achieved or exceeded their savings targets, as well. While a final accounting from the administration is coming later this year, some uncertain designations under EO 13,771 could make the administration’s tally somewhat different from AAF’s projection.