Weekly Checkup

November 9, 2018

What Does the Election Mean for Health Care Policy?

If you’re wondering what the Democratic takeover of the House and the slightly larger Republican majority in the Senate mean for health care policymaking in the immediate future, the short answer is: probably not that much.

The current Congress has reached something of a legislative stalemate when it comes to major health initiatives, and the elections were not going to change that reality. True, the 115th Congress has seen some accomplishments on health care. Some of those—e.g. opioid legislation—did not depend on unified party control of both chambers. Others—such as the repeal of the individual mandate penalty and delays of many Affordable Care Act (ACA) taxes—stretched the Republican majorities almost to their breaking point. But Congress couldn’t repeal the ACA during the 115th, and Republicans likely wouldn’t have been able to do so in the forthcoming 116th even if they held the House. Similarly, Congress couldn’t reach a deal on an individual market stabilization package, and again there wasn’t much reason to believe the election would change that. The margins in the House and Senate, and the divisions within the GOP conferences, weren’t going to change enough to open up a path to partisan bicameral policymaking even if the GOP had held the House.

Ultimately, major policymaking in health care over the next two years will take place within the agencies through the rulemaking process. In fact, much of the significant policymaking already has been occurring through agency actions. (See recent examples here, here, here, and here.) Again, this would have been the case regardless of party control. So, when it comes to new health care policies during the 116th Congress, look to the Department of Health and Human Services.

All this is not to say that the Democrats’ return to power in the House is irrelevant. The administration will find itself facing aggressive opposition in its rulemaking efforts, especially when related to the ACA. Perhaps more important will be the way that a Democratic House shifts the policy conversation. Medicare-for-All and other single-payer initiatives will gain valuable, profile-raising debate time in House committees and even on the House floor. There may also be an opening for legislation on prescription drug prices, as the president’s policy preferences on that matter already lean in the direction of the House Democratic caucus.

The Democrats will find legislating difficult, though, just like Republicans did. Most of the actual policymaking over the next two years will happen in the executive branch.

Chart Review

Tara O’Neill Hayes, Deputy Director of Health Care Policy

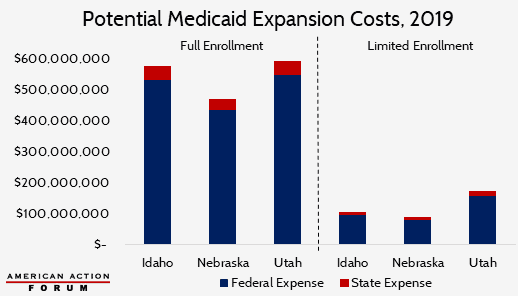

On Tuesday, residents in three states voted to expand Medicaid eligibility, bringing the total number of expansion states to 37 (including the District of Columbia). In 2019, the federal government will fund 93 percent of each state’s Medicaid expansion costs, before declining to 90 percent in 2020 and each year thereafter. The following chart shows estimates of the potential range of costs for each of these states in 2019. On the left is the cost if all eligible individuals (119,000 in Idaho; 86,000 in Nebraska; and 158,000 in Utah) take advantage of the new opportunity. On the right is the cost if only those in the “Medicaid coverage gap”—i.e. those caught between current Medicaid eligibility and ACA subsidy eligibility—enroll. The resulting numbers create a likely upper and lower bound for the annual cost of expanding Medicaid in these states.

Worth a Look

Reuters: U.S. companies team up with hospitals to reduce employee maternity costs

Modern Healthcare: Azar says new mandatory oncology pay model is coming