Weekly Checkup

December 20, 2019

A Surprisingly Busy Week in Health Policy

Tracking federal policymaking is largely an exercise in waiting around for something noteworthy to happen. But occasionally a lot of things happen all at once. And so, one of the slower years for health policy is ending with less than a bang, but certainly more than a whimper—portending a (potentially) exciting 2020 for health policy.

The big story to start the week was that Congress actually did something on health care, repealing three major Affordable Care Act (ACA) taxes—The “Cadillac” tax, the medical device tax, and the health insurance tax—in one fell swoop as part of the year-end spending bill.

The Cadillac tax, a 40 percent excise tax on particularly rich health insurance benefits, was originally included to keep downward pressure on health care costs and to provide funding for the ACA’s benefits, but the tax has been delayed twice, never implemented, and now has been repealed. The reality was the Cadillac tax was a poorly designed, blunt instrument, and the tax has always been a point of contention between labor unions—which are especially impacted by the tax—and Democrats. Republican lawmakers, for their part, are always happy to kill a tax. Yet the tax served a necessary purpose. Repealing it without replacing it with something better is bad policy.

The medical device tax was a 2.3 percent excise tax on all medical devices sold in the United States. The medical device tax was entirely about funding for the ACA’s coverage provisions and served no other purpose. The tax took effect in 2013 but was suspended in 2016 and repeatedly since. Manufacturers paid the tax on their gross revenue, not on their profit, so in effect it could put many smaller companies and startups into the red and out of business. In fact, AAF has previously estimated that permanently repealing the device tax could save upwards of 53,000 jobs that would have been lost if the tax stayed on the books.

The health insurance fee—really a tax—was also about paying for the ACA’s generous benefits. The theory was that the individual mandate, paired with subsidies, would create new business for insurers, and so it was reasonable for them to help finance the law. Insurers pay a fee for each plan they sell, but the problem is that this fee is simply passed on to the consumer in the form of a higher premium. This tax has been delayed ad nauseum—some years it’s in effect, some years it isn’t—and repealing it is sensible. It is a little surprising, however, that Congress chose to do so, considering neither party particularly like insurance companies at this juncture, and the frequent delays provided leverage moments when negotiating with them.

Alone, these actions would make for a big week, but we’re not done. The Trump Administration issued two proposed rules this week, the first a formalization of its long-expected Canadian pharmaceuticals importation plan. Read more about that here, here, and here. The second rule aims to remove some of the restrictions on compensation for live donors who agree to donate, say, one of their kidneys or a portion of the liver. Threading the needle between paying people for their organs and allowing them to receive compensation for the costs associated with their donation could be long-term positive to the health care system, and the proposal bears watching.

But of course, you’re reading today to hear about Texas v. Azar, the legal challenge that could ultimately lead to the Supreme Court striking down the ACA in its entirety. Plenty of ink has been spilled already on the history and particulars of the case (read here, here, here, here, and here), so I won’t review. The Fifth Circuit ruled this week that the individual mandate is unconstitutional, but the lower court must now reexamine whether any of the law’s provisions can be left intact or if the entire law needs to be struck down. The ruling is certainly a big deal, as this is probably the most danger the ACA has been in since NFIB v. Sibelius in 2012. But it’s also not that big of a deal, because the ruling is not a surprise and this case was always going to end up before the Supreme Court. For now I’ll leave to the court watchers to speculate on what the Roberts Court will decide, but the decision could be announced during the heat of the 2020 presidential election, making for some interesting politics.

The bigger picture is this. Opponents of the ACA have already effectively repealed the individual mandate, and along with the law’s supporters have slowly but surely rolled back most of the financing provisions (in many cases for good reason). If the Court strikes down the rest of the law, opponents face a conundrum. They have so far been unable to rally around a comprehensive alternative to the ACA, and the political realities of a court decision against the ACA could lead them to reinstate many of the law’s spending provisions. How ironic if Republicans finally kill Obamacare, only to revive it as TrumpCare.

Chart Review

Andrew Strohman, Health Care Data Analyst

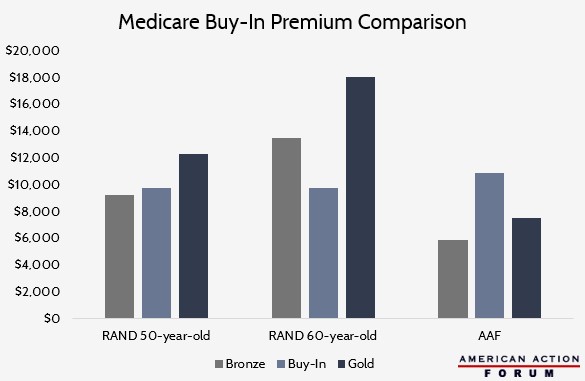

The RAND Corporation recently published a report assessing the potential impact of a Medicare buy-in. While its results on enrollment are similar to those reported in AAF’s model of H.R. 1346, which would also allow those aged 50-64 to enroll in Medicare, there are some differences in its projected premiums. AAF’s projected 2022 average buy-in premium is $10,900, significantly higher than the $9,747 premium projected for both 50- and 60-year-old buy-in enrollees under RAND’s projection for the same year. Additionally, AAF projects the buy-in premium will be higher than both the average Bronze and Gold plans, while RAND expects buy-in premiums to be lower than at least the Gold plan.

These disparities may come from subtle differences in assumptions for the modeling. While both assumed actuarial values (AV) of 80 percent (equivalent to a Gold plan) and roughly the same national average ratio of payment rates (between 84-86 percent), RAND assumed that those who qualified for cost-sharing reduction (CSR) payments would receive plans with AVs of 94, 87, and 73 percent as household income approached 250 percent of the federal poverty level (FPL). AAF specifically modelled H.R. 1346, using its proposed expanded CSR eligibility with AVs of 95, 90, and 85 percent up to 400 percent of the FPL. Furthermore, AAF assumed the reintroduction of an individual mandate penalty while RAND kept it zeroed out. Finally, RAND seems to model the average premiums offered while AAF models premiums paid. These alternative assumptions may explain the different final premiums.

Data obtained from RAND and AAF

From Team Health

Obstacles to Success of the Drug Importation Plan – Deputy Director of Health Care Policy Tara O’Neill Hayes

Numerous challenges facing the Trump Administration’s importation policy suggest it will struggle to lower drug prices.

Daily Dish: The ACA and the Courts (again) – AAF President Douglas Holtz-Eakin

The latest court decision about the Affordable Care Act means that the law is once again a live political issue.

Worth a Look

Axios: The ACA legal fight isn’t even close to over

New York Times: Doctors Win Again, in Cautionary Tale for Democrats